Unprecedented political stability and surging hydrocarbon exports have provided a platform for a remarkable recovery from the depths of Russias 1998 crisis, but structural problems linger.

On February 11, UK oil giant BP announced it was investing $6.75 billion in a joint venture with Tyumen Oil Co. (TNK) in Russias largest-ever equity dealand a move that matched the amount of FDI in the whole of the country over the preceding three years.

Russias RTS stock index jumped 2.7% on the news, as participants and observers alike predicted a flood of copycat deals that would cement Russias return from the pariah status that dogged it since its 1998 financial crisis.

Theres been a change in Western attitudes, says Mikhail Fridman chairman of Alfa Group, one of two major shareholders in TNK. We are now regarded as not just oligarchs but just normal big businessmen with our own interests. The BP move was widely dubbed all the more significant as the company had become entangled in a highly publicized spat with Fridman and allies over a 2001 joint venture with TNKs fellow oil company Sidanco.

Who better to paint a big story of support than someone who has been burnt in the past? says William Browder, the CEO of fund manager Hermitage Capital Management in Moscow and a seasoned jouster with entrenched interests in post-Soviet Russia.

BPs hunger for new oil reserves dovetailed neatly with TNKs desire to realize some of its investment in the oil industryand inject some much-needed Western expertise. But thats a story that can be played out across much of Russian industry.A small group of hard-headed businessmen have wrested control of large parts of the countrys economyranging from oil and gas through metals and energyand have plugged the leaks and cleaned the companies up to international standards. The oligarchs effectively have come to terms with Russian Federation president Vladimir Putin, rendering unto Caesar what is Caesars: Theyll run their companies efficiently, stop the most egregious asset-stripping and pay their taxes. In exchange, Putin will let bygones be bygones and not pry into how post-Soviet assets were so ruthlessly corralled into so few hands.And by re-establishing the rule of lawcleaning up the courts, reining in wayward provincial governorsPutins made Russia a safer place to do business.

Thats good news for a group of businessmen making the transition from hunter-gatherer to farmer. Like it or not, its been good for Russia, too, aligning these key owners interest with those of their companies and their shareholders. The attitudes of management are changing faster than the legal landscape itself, says Anya Goldin, a partner in the Moscow office of Latham & Watkins. Breaking the rules doesnt pay as much any more.

Across large swaths of the Russian economy,thats made leading businessmen agents of change. In doing so, this process has finally begun to deliver some of the promise of an economy so long snowed under by mismanagement, corruption and unenforceable laws. And that has finally made large sections of the Russian economy attractive enough for foreign investment.This is a huge consolidation and restructuring play, says Steve Jennings, CEO of Renaissance Capital,a Moscow investment bank.

But headline deals like the TNK/BP link-up are few and far between. There are other clear signs that investors have woken up to the attractions of the New Russia. International buyers have long dominated trading volumes in stocks such as oil giants Yukos and Lukoil; between 70% and 80% of trades in those shares are between overseas buyers, say analysts.

Re-rating of the oil sector has finally shifted a stock market mired for much of last year by wider emerging market woes, says Al Breach, chief economist at broker UBS Brunswick Warburg.The RTS index has risen by 8% this year, against a dismal background for emerging-markets stocks.

The countrys top-flight companies have found overseas investors ever more ready to buy their IOUs. In February the worlds largest gas company, Gazprom, issued a $1.5 billion eurobond, the largest yet in emerging markets.

And private equity firms are again circling the country, with new money lining up along some players who have been in Russia during previous ups-and downs.There is an enormous change in the investment climate today compared to before 1998, says Michael Calvey, joint CEO of Barings Vostok Capital Partners, a private equity firm that has been investing in Russia since 1994.

For many,these are tangible signs that Russias post-1998 rebirth is real.The optimists are right this time,says James Fenkner, chief equity strategist at Troika Dialog, a Russian investment bank.That may be, but as with any boom, its crucial to untangle the structural from the cyclical.

Rocketing oil prices have flooded state coffers with cash, making the process of reform far less painful. Russia has paid down $60 billion of debt since 1998,has foreign currency reserves of over $50 billion and had a debt-to-GDP ratio of just 30% at the end of 2002.

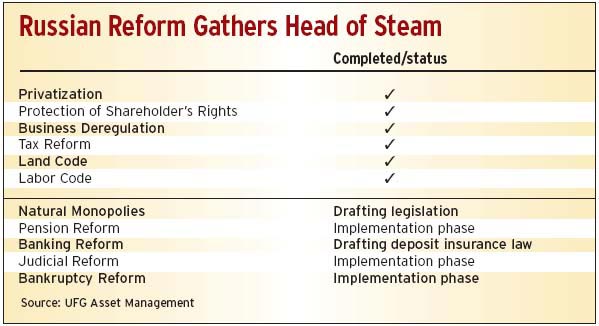

Thats allowed Putins government to push through important reforms in the area of taxation, the courts and the regulatory regime that has hemmed in Russias businesses, especially smaller and medium-size enterprises. The number of licenses that a company typically has to obtain to do business has been slashed, though the price for obtaining these has tended to rise, says Christof Rhl, chief economist at the World Bank in Moscow. Heavy regulation is one reason why small and medium-size businesses employ just one in four Russian workers, compared to two out of three in the European Union.

Some reforms are still squeezing through: In February deputies finally voted for a much-delayed break-up of monopoly energy utility United Energy Systems. But experienced Russia-watchers know that in the run-up to Duma elections in December 2003 the current government is unlikely to push through any reforms likely to alienate significant sections of Russian society.

Putin is extremely risk-averse,says Hermitage Capitals Browder. If he were a fund manager, hed have 1.5% returns with no defaults.

But taking the foot off the gas pedal might combine with a weakening of the economic landscape to mean that Russia misses the chance to fully reform its economy. In an October 2002 report that was debated by the Russian cabinet, the World Banks Rhl argued that high oil prices and political stability had allowed reforms to be carried out at unprecedented depth and speed, but that these favorable external conditions are unlikely to last forever. Only then will it be clear whether the economy has changed enough to adapt to adverse circumstances, says Rhl.

There are already signs that policymakers are bobbing in the wake of economic success. Currency devaluation was the other ingredient in the macro-economic recipe that propelled Russia out of its post-1998 trough, but that trend has been abruptly reversed, as surging oil imports pump up the ruble.

The Russian government has forecast GDP growth of 4% for 2003, but with large sections of the Russian economy untouched by the benefits of high oil prices, many doubt that can be achieved.

And hanging over the whole equation is the uncertainty caused by Iraq. If Iraqi oilfields start pumping soon after the war ends, oil prices may plunge. The Russian government is commonly thought to balance its books at an oil price of around $16 per barrel, way below the current levels but perilously close to a 20- year average of $18.

The changes that have swept Russia in the past few years are real enough, and a 1998-style bust is almost inconceivable. But the memory of those dark days lingers enough to inject a note of caution to the hymns of praise to the new Russian economy.

Please, not another euphoria, says Goldin.There is always more continuity than change in Russia.

|

If booming gas and oil companies are the face that Russian industry presents to the world, then the visage staring back from the mirror is an altogether more mottled one. In January the closely watched Purchasing Managers Index published by Moscow Narodny Bank dipped into the red, signaling a contraction in manufacturing industry for the first time in four years. The index, which tracks purchasing managers at 300 companies, crept back over the neutral mark in February, but few observers expect that to mark anything other than a temporary respite.

Much of Russian industry lies becalmed, laid low by a combination of vanished markets, insipid investment and the playing out of the artificial boost provided by the post-1998 ruble devaluation. These companiesin traditional rust-belt industries such as textiles, engineering and machine toolshave failed to attract the capital or the new investors that have revitalized sectors such as food processing and retail on the one hand and the natural resources sector on the other. That tripartite structure has become known as the Russian sandwichand, unappetizing as it may be, its one item that has forced its way onto the menu of Kremlin policymakers. Aware of growing imbalances in the economy, economic development and trade minister German Gref in February unveiled a strategy to save the Russian economy from Saudi-Arabiaization. Higher natural fuel taxes were the pull, investment stimuli the push. That might work, but few are holding their breath. The World Banks Christof Rhl points out that the gap between the primary and secondary sectors of the economy is not only wide; its widening. Between January and September 2001, growth in resource-oriented industries accelerated from 5.4% to 6.5%, while output growth in the manufacturing sector slowed from 5.5% to 3.3% over the same period. Does that matter? Some say not. Hermitage Capital fund manager William Browder says that Russia is just not very good at making things that consumers want to buy. Streets in Moscow and Nizhiny Novgorod are increasingly full of foreign cars, for example, and less than one television in a hundred is made in Russia. And despite their volatility and susceptibility to geopolitics, the argument over dependence on natural resources can be overdone, says Steve Jennings, CEO of Renaissance Capital. Canada, New Zealand and Australia all have higher percentages of GDP in the primary sector, he argues, yet stand among the most successful economies in the world. |

Battle for Control

For all the talk of foreign investment returning to Russia, this is still a game being played out more in the boardroom than on the trading floor. By Mark Johnson

If the freewheeling,anything-goes days of Russian capitalism are largely in the past, key players are moving into a new gameone where the rules are a little firmer. Russian entrepreneurs have moved aggressively to clean up companies they won, getting a firm grip on cash flows and plumbing leakages, says Steve Jennings, CEO of Renaissance Capital.Once one firm starts it in one industry, the others are able to copy them.

Oil giant Yukos makeover set the tone: Simplifying the companys ownership and control structure and revealing its beneficial ownership ramped up the share price hugely.Thats made it easier to seek a listing on the New York Stock Exchangeone of the strategic options being considered by CEO Michael Khodorovsky. Less glamorous companies are mulling this route, too. Engineering conglomerate United Heavy Machinery is planning a London float in the fall, following a restructuring program partly aimed at making the company more comprehensible to the outside world.

But as ever, the road to union between Russian assets and Western capital may not be that straightforward. Portfolio investors remain vulnerable in Russia.Western companies often feel happier taking strategic stakes that give them real management leverageand the premium they are prepared to pay up for the privilege makes that an attractive option for Russian sellers. Economic agents are acting very rationally, says Jennings.They are moving from strong Russian shareholdings to strong multinational structures, he notes.

|

Few foreign visitors to Moscow are likely to miss the distinctive blue and yellow colorways of the IKEA shed on their way to and from Sheremetyevo Airport, nor the irony of its locationnext to the giant tank traps that mark the highwater mark of the German advance in the winter of 1941.

But for Muscovites, the store is no exercise in the juxtaposition of the heroic and the banal. Since it opened in March 2000, the hulking shed has averaged more than 45 million customers a year, making it the most-visited IKEA store in the world. Whats more, those visitors are not just coming to window-shop; instead, they spend an average of $70 a visit on a par with IKEAs Swedish customers. But if the store, since joined by two others, is a testament to the pent-up desire for affordable, well-made consumer goods among Russias 145 million citizens, its also a rarity: a successful greenfield investment by a foreign company. For the truth is, Russias record on FDI is woeful. According to the State Statistics Committee, foreign companies invested just $4 billion in 2002, hardly more than the 1999 total of $3.3 billion. Thats especially poor compared to the record of countries like Chinaa country that sucked in more than $53 billion of FDI in 2002. To be sure, the figures dont tell the whole story. Wary of the vagaries of the Russian legal system, many foreign companies insist on deals being inked offshore, meaning they dont enter the official numbers. Andrew Somers, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia, points to two recent American investments. General Electric recently said it would open a locomotive plant, while Ford has a full order book for its new plant in Togliatti, Russias Motor City. In February French automaker Renault announced a $250 million investment in Moscows Avtoframos factory, a joint venture with the city government. The money will tool the plant to produce the X90, a sub-$10,000 family sedan designed to cope with the ups and downs of Russias climate and road system. That ought to make the X90 a natural for export to other emerging countries, but as Christof Rhl, chief economist for the World Bank in Moscow, points out, high customs barriers have all but smothered the emergence of a Russian re-export sector. |

Alfa Group chairman Mikhail Fridman says that he and his partner in TNK will not be passive investors in the new venture:We are not yet ready to become pensioners, he says. But the rendering up of assets to foreign players with access to far deeper capital and management fits neatly into his game planand those of some other Russian businessmen.

Some Russian accounts are trying to diversify away from their reliance on natural resources, says David Jones, CEO of the Moscow arm of Delta Capital, a private equity firm active in Russia since 1995.Russians are buying their own economy, says Florian Fenner, managing partner at Moscow financial group UFG Asset Management.Foreigners have not come yet.

Theres still argument over the exact size of the reversal in capital flight.According to figures from the State Statistics Committee and Troika Dialog, capital outflow slowed to an estimated $17 billion in 2002, down from $28 billion in 2000but theres no doubt over where the trend is now heading.Capital flight is now a non-event, says Fenner.

Hometown knowledge and deep pockets have made Russian buyers powerful competitors to drive the reshaping process so clearly needed by much of Russian industry.They are our main competitors, says Michael Calvey, a co-managing partner at Baring Vostok Capital Partners, a Moscow private equity firm.

Calvey estimates that Russian investors have around $10 billion in ammunition or around 98% of the market. Recycling funds into other sectors of the economy often places Russian businessmen firmly into the same territory as private equity funds. For some its been unloved industries such as tire-making and pulp and paper;for others its been food-processing and agricultural land. Dont read that as some misty-eyed return to the land but rather a shrewd realization that theres money to be made outside the commanding heights of the economy. Domestic and overseas equity players all have their eyes fixed on opportunities generated by the swelling Russian bourgeoisie. We are firmly targeting the growing consumerism of the middle class, says Deltas Jones.

Helping a budding entrepreneur straight out of Artillery School grow a bakery business into a 10-strong chain of cash-and-carries centered on the Volga city of Nizhiny Novgorod was one investment. More visible still is Delta Capital, a Moscow start-up that aims to kickstart Russias fledgling home-loan market.With the help of a 40 million loan from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Delta is lending out to 10 years for Russians keen to buy their own apartments.

In September Delta Finance unveiled a new creditcard product aimed at customers of fast-growing furniture chain IKEA. Investing private equity in Russia is still not a game for the faint-heartedand some private equity investors retired hurt from Russia after 1998. For those who stayed, there have been some rich pickings. Baring Vostoks first fund has returned $300 million so far, on capital of $160 million.With investments outstanding in five companies, Calvey hopes to return a further $400 million to investors, yielding an expected internal rate of return of around 30%.

With private equity in the doldrums elsewhere around the globe, its little wonder that other private equity groups are looking to raise new funds. Delta is set to close a $100 million fund targeted at Russia in April. Other firms believed to be raising private equity funds include New Yorks Siguler Gulf and Genevabased Finartis.

But if the environment is the best it has ever been, industry titan Texas Pacific Group was forced to concede defeat in its attempts to raise a $250 million fundit would have been TPGs second venture into the country while AIG is still struggling with its planned fund.

In fact, the best-placed investors may be those institutions that already have hometown knowledge and connections. Russias UFG is linking up with Gleneagle.Even the tycoons themselves are at it. Alfa Bank is mulling establishing co-funds that will attract foreign money to joint investments in Russia, says Mikhail Fridman. Powerful friends, indeed.

Banking Sector Wrestles With Change

Water,water everywhere, nor any drop to drink. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Banks lend; companies and individuals borrow. Thats a banking maxim that works throughout the world but only, it seems, sporadically in Russia. The 1998 crisis shuttered bank branches across the country and left many of the survivors as walking wounded. Stung by losses, citizens reverted to keeping notes under mattressesas much as $90 billion on some estimateswhile bank officers put on their stoniest faces when approached for loans. It can be pretty difficult to get money, says Marina Nacheva, a spokesperson for United Heavy Machinery, a Moscowbased conglomerate of capital-intensive industries such as shipbuilding, drilling and nuclear plant construction. She says there is often only one bank offering funds at a reasonable rate.

Outside the hydrocarbon and minerals sectors, thats an experience reflected across Russian industry. Russian companies typically generate around 50% of their financing from internal means prudent, maybe, but hardly a recipe for a growing economy.

Little wonder, then, that bank loans to the corporate sector account for just 12.3% of Russias GDP, well below the 25% average for Eastern Europe or 38% for Latin America. The banking sector is just not becoming an independent center of finance, says Christof Rhl, chief economist for the World Bank in Moscow.Thats important: As the Rhl points out, in developing economies its banks that are the key engines of financial intermediation, not capital markets.They are better at controlling those risks, he says.

Andrei Ivanov, a banking analyst at Troika Dialog, puts some of the reluctance to lend down to the shape of Russias banking system. He points out that banks reflect distortions in the economy as a whole, with capital clustering among institutions related to the countrys commodity producers, and the state playing a dominant role.

In banking terms, the state means one thing, above all: Sberbank, the majority state-owned savings bank that accounts for around 75% of all deposits in Russia. That makes reform of Sberbank crucial to the future of the banking system,says Vladimir Rashevsky, CEO of MDM Bank, one of the fastest-growing banks in Russia. Like other critics, he favors eventual privatization of Sberbank; in the meantime, the planned introduction of deposit insurance may narrow the competitive gap with the savings bank, which depositors typically view as state-guaranteed.

|

Russias leading companies have become ever-morefrequent visitors to international markets, but until recently issuing debt was something about which the average Russian corporate treasurer could only dream. Thats changing, thoughand fast, as a domestic corporate bond market has mushroomed before their very eyes.

According to figures from Troika Dialog, Russian companies issued some 35 billion rubles of IOUs in 2002, taking advantage of the swelling pool of petroruble liquidity looking for a home. That reflects a greater confidence in the Russian economy, as money that would once have stayed offshore is now repatriated. A stable currency has provided the underpinning for this growth, while juicier yields and favorable tax treatment has added luster to corporate IOUs when compared to those issued by the central government, regions and municipalities. Troika Dialog estimates the domestic corporate bond markets will swell to around 160 billion rubles by 2004, or 10 times the level at the start of 2001. For cash-hungry companies looking for working capital, thats a dream come true: Bonds typically cost around two percentage points less than bank loansif they are available and the length of time for which companies can borrow money is edging out to as long as a year. Scratch the surface of this growth story, though, and some doubts begin to surface. Its the same banks that are so reluctant to intermediate financing through ordinary corporate overdrafts that are providing the raw material for this lending boom. According to Troika Dialog, Moscow-based banks account for 45% of the buyer universe for company bonds, with regional banks adding another 10%. Konstantin Malofeev, head of corporate finance at MDM, says his bank picks issuers very carefully. Other underwriters may be less discriminating. The lack of a common ratings system and feverish competition among 30-plus would-be underwriters looks like a recipe for a bust to any seasoned observer of capital markets. Already, one borrower has flirted with default. There is potential for a bust, admits Troika Dialogs James Fenkner, but there needs to be a boom first. We are not anywhere near that problem. Turkish companies are three times more leveraged on average, he notes. |

Its not just rival bankers that Sberbank has up in arms; the central bank has tried to force the lender to reduce its exposure to a couple of top-flight corporate names, so far with little success. Project loans to finance capacity increases at domestic companiesmostly energynow account for 30% of Sberbanks book.

But its not just Sberbank doing the cherry picking. International bond buyers are now happy to lend to top Russian corporates at rates comparable to those they charge the countrys banks. Theres no margin for us, says Rashevsky.

Fat Margins Fail to Tempt Banks

Thats a complaint common to banks the world across, but its in lending to the swaths of companies below the top crust that Russias banks really fall down. Its not for the lack of juicy margins: The State Statistics Committee estimates the real rate charged on corporate loans at between 22% and 25%. Rather, its the stunted nature of a credit culture in Russia thats doing the damage. Strong links to industrial groups mean that many banks perform more as inhouse treasuries rather than efficient mobilizers of capital for the economy as a whole, argue critics.

Thats an out-of-date criticism, contends Mikhail Fridman, chairman of Alfa Bank. Along with a few other businessmen, Fridman has made efforts to transform his bank into the kind of institution that would pass muster by international standards with professional management and systems.

Thats helped banks like Alfa and MDM pull in greater levels of deposits and attract foreign funding through the eurobond markets, but the amount of resources funneling through to the corporate sector has remained a fraction of what is needed. Thats partly down to lack of trust within the banking system; theres almost none of the syndication of risk that allows banks to advance large loans elsewhere.

Foreign Banks Fill the Gap

Foreign banks have stepped in to fill some of the gapsbut only some. With other foreign banks having pulled out of Russia after 1998, foreign lenders account for just 7% of banking assets in the country.

Still, some of those that have stayed have carved out substantial niches for themselves.

Michel Perhirin, chairman of Raiffeisen Bank in Russia, says his bank has built up a book of more than $1 billion in the country. Thats been helped by a swelling roster of depositors. But even he admits that despite the plethora of recent good news over the economy, it can be hard to generate enough interest.Funds are not easily available for this country, says Perhirin.

Companies are making efforts to get around that logjam: United Heavy Machinery is mulling setting up a leasing company to provide customer financing, says Marina Nacheva.

Mark Johnson