Its not uncommon for corporate financial officers to cut billion-dollar checks these days as they shore up the sagging balances of their company pension funds.

Three years of plummeting equity returns and some of the lowest interest rates in four decades have combined to push the balances of corporate pension plans into negative territory. Instead of enjoying the stellar equity returns of the late 1990s that left many of their defined benefit plans flush with cashand even producing incomecompanies are scrambling to ante up billions of dollars to make sure their pension plans are no longer underfunded.

In the past few months, Coca- Cola, General Motors and Ford Motor have been among a slew of companies that announced they are making significant contributions to their plans or lowering the assumed rate of return their existing pension fund dollars will generate in the coming year. Just in the last two weeks of September, tens of billions of dollars shifted from corporate checking accounts into corporate pension funds, says Ethan Kra, chief actuary at Mercer Human Resource Consulting in New York.Theres no Christmas tree, and the money has to come from somewhere.

And experts say that money is being diverted from a variety of corporate functions: paying dividends to investors, improving compensation for existing employees, hiring new workers, investing in new businesses and paying down debt.Whats going to affect companies profits is that they wont have the money to invest in a plant or buy new computers, Kra says.The typical pension plan is expected to earn money; now companies have a big hole to dig out of.

And from a Credit Suisse First Boston study released last fall:The declining health of defined benefit pension plans may result in companies diverting the cash that they have set aside to grow the business, buy back stock, pay down debt or pay dividends, and pour it into the pension plans.

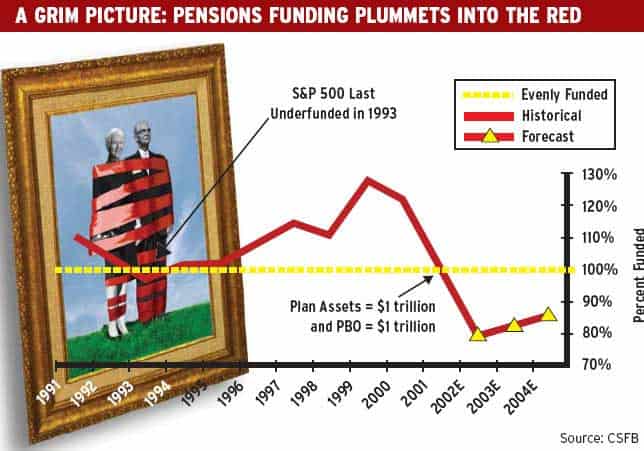

US pension funds are still by far the largest source of retirement savings in the world. According to a report published mid-January by consultants Watson Wyatt, their $6 trillion-plus of funds at the end of 2002 accounted for 56% of the worlds total. Still, slumping stock markets slashed $900 billion off their value in the past three years. Thats likely to cause pain at the corporate level.CSFB,which focused on the 360 companies in the S&P; 500 Index that have defined benefit pension plans, estimated that the plans could be underfunded in aggregate by $243 billion at the end of 2002.That would be the first time the plans have been underfunded since 1993 and would mark a huge shift from the $252 billion surplus chalked up at the end of 1999.

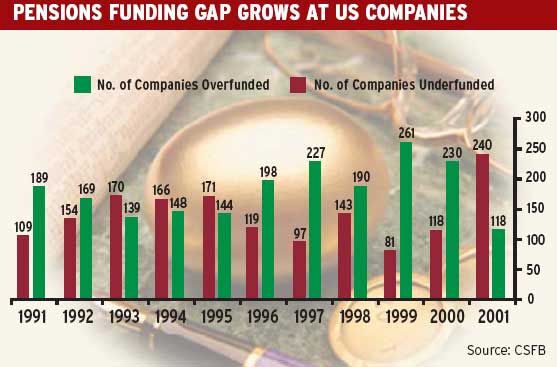

Credit Suisse analysts say the number of companies with underfunded plans tallied 240 at the end of 2001,the highest level in the past decade, and predict that as many as 325 companies may be in negative territory by the end of 2002. The report also says that companies in five industry groupsautomobiles, auto components, oil-and-gas, pharmaceuticals and airlinesaccount for the majority of troubled plans.

The 2002 study is based on analyzing the corporations 2001 financial data,which was included in the annual 10-K filings released in March 2002.A new study looking at 2002 numbers will be started once the new financial data is released at the end of March.

In addition to making large contributions to their pensions plans,corporations are also cutting the expected return on their pension plan assets. Executives at Atlanta-based Coca-Cola, for example, announced in December that they were lowering the expected return on the companys pension plan assets to 7.5% in 2003, down from 8.5%. The soft drink giant also said it was injecting $150 million into its $2.5 billion pension plan to keep it fully fundedmoves that would negatively affect company earnings by 1 cent a share this year. That was the first time it had made a contribution since 1997,when it contributed $9.4 million, followed by $14.2 million in 1996 and $44.5 million in 1995, according to Coca-Cola spokesperson Kari Bjorhus. General Motors has estimated that its US pension plans were underfunded by $19.3 billion at the end of 2002, up from a liability of $9.1 billion at the end of 2001. The Detroit automobile company announced in December that it would make a contribution of $14 billion to $17 billion to its defined benefit plan between 2003 and 2007. Pension drag might make it hard to hit the $10 earningsper- share target by mid-decade, says GM CFO John Devine. The company announced in January that it was going to reduce the assumed rate of return on its assets to 9% in 2003, down from 10% in 2002.

That might not be enough, says Jeremy Gold, an actuary and head of Jeremy Gold Pensions in New York City. Assuming 9% in a 5% world is out-of-line, says Gold, who works as a consultant to both corporate and public plan sponsors. The actuaries are too optimistic. The system is flawed and needs repairs. He says one corrective measure might be for pension funds to report the actual returns on assets, rather than the expected returns on assets.You dont anticipate returns before making them, he adds.

But Jerry Dubrowski, a GM spokesperson, says it is important that companies dont overreact to the market downturns and subsequent pension fund liabilities. We didnt get into the pension hole overnight,and were not going to get out overnight, says Dubrowski.The pension fund issue is a significant issue, but a manageable issue.Were managing the pension plan for the long-term horizon. He adds that the companys pension plan, valued at $67 billion at the end of 2001, has generated an average annual return of 10% over the past 15 years. The companys assets are also invested in a highly diversified portfolio that includes domestic and international equities, fixed-income securities and real estate. Markets also turn upward,he notes,and a 1% increase in interest rates would wipe out $7 billion in the companys pension plan liability.

Corporate pension plans are under pressure as the number of retirees outpaces the active employees supporting the plan. General Motors, for example, which started its defined benefit plan in the 1950s, now has two-and-a-half retirees for every active employee, Dubrowski says. As yet, nobody can predict when corporate executives will be able to breathe a little easier. If anybody tells you that, theyre hallucinating or lying, says Mercers Kra, adding that 2002 was a horrific experience, with interest rates dropping and the market tanking,

Kra says company management is only just waking up to the scale of the problem.In the past six months, this has gotten a lot of visibility at the board level, he says.CFOs, COOs and CEOs are talking about the problem. Some companies may not be able to continue the promise.

Paula L. Green is a New Yorkbased contributor to Global Finance.

Email: pgreen@gfmag.com

By Paula L. Green