Recent financial turmoil has accelerated the seismic shifts taking place in the balance of global economic and political power. How the major powers act in the coming years will determine the future shape of globalization.

BY LAURENCE NEVILLE

The global economic crisis has called into question many of the tenets of the world economy. The free markets that have dominated economic orthodoxy for decades have been shown to have significant shortcomings. And the reactions of governments around the world have demonstrated that seemingly sacrosanct commitments to free trade can be easily discarded.

The global economic crisis has called into question many of the tenets of the world economy. The free markets that have dominated economic orthodoxy for decades have been shown to have significant shortcomings. And the reactions of governments around the world have demonstrated that seemingly sacrosanct commitments to free trade can be easily discarded.

As a consequence, globalization—a relentless historical trend since colonization and one that has accelerated to change the world beyond recognition in recent decades—is under scrutiny. What will this new version of globalization look like? What countries will see their role in global economic and political affairs enhanced in this new world?

Some observers herald the Group of 20 meeting in London in April as proof that a new era has begun, in which developing countries will play a more important role. Others argue that the implosion of Western finance will create only one winner from the developing world: China. Still others believe that the United States can recover its preeminence and reign supreme over the world economy for decades to come.

WHY GLOBALIZATION WILL CHANGE

The scale of the economic crisis that began 18 months ago still retains the power to shock. Global trade volumes are expected to fall by more than 10% this year—by far the sharpest contraction in the post-World War II period. The International Monetary Fund in April again downgraded its expectations for global growth and now expects a contraction of 1.3% this year. The IMF describes the downturn as “by far the deepest global recession since the Great Depression.” Meanwhile, annualized industrial output is down by 38.4% in Japan, 20.6% in Germany, 12.8% in the US and 12.2% in the United Kingdom, based on monthly figures for April.

Such trends highlight the shortcomings—in the opinions of many in developed and developing countries—of the global economic system, designed by the developed Western countries following World War II. As if the evidence of the failure of capitalism as currently practiced was not clear enough, Western governments’ reactions to the crisis have further undermined the credibility of the global economic status quo.

“This kind of deep recession and crisis inevitably encourages countries to turn inwards, [to] become more protectionist and increase regulation,” says Russell Jones, global head of fixed income and currency research at RBC Capital Markets. “The industrialized core countries have hardly delivered the best message; for example, France has encouraged its auto companies to repatriate factories from CEE [Central and Eastern Europe].” Meanwhile, having lectured developing countries on subsidies for decades, the United States has delivered huge bailouts for the finance and auto sectors. “Consequently, globalization and the opening of markets have been delivered a sizable hit,” says Jones.

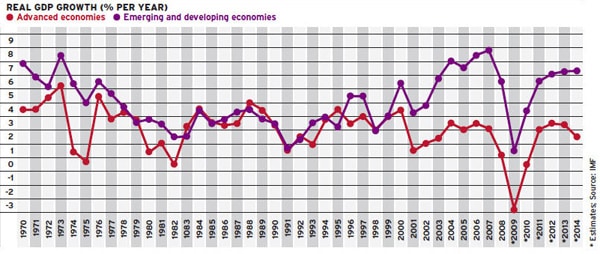

At the same time, it is becoming clear that the pain of the economic crisis will not be shared equally. “Many emerging market countries have already completed the necessary reforms to recover from the crisis and, in any case, are less exposed to financial services and consequently are less damaged than the West,” says Alex Barrett, head of client research at Standard Chartered in London. “As a result, they will be less affected, and there will be an acceleration of the movement of economic power from the West to the East—and ultimately perhaps even political and military power.”

Martin Jacques, academic and author of When China Rules the World: The Rise of the Middle Kingdom and the End of the Western World, believes that this movement of power is part of a longer process. “There has been—and will increasingly be—a relative decline of rich countries in the West in terms of their share of GDP and a rise of developing countries. In particular, it’s about the rise of China but also to a lesser extent about Brazil, India and other countries.”

WHO GETS THE NEW POWER?

The G-20 meeting in April was widely interpreted as heralding an era less dominated by the G-7/G-8. But some have questioned whether the G-20 grouping, which was a pre-existing but unimportant body, will be relevant in terms of power. And others have asked whether the invitation to developing countries to help reshape the global economy isn’t merely a sophisticated ruse to enable the West to retain power.

“The G-20 is certainly a helpful grouping because it represents a much greater part of global trade flows than the G-7,” says Nigel Rendell, emerging markets strategist at RBC Capital Markets. The G-20 grouping, which includes Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, South Africa, South Korea and Turkey, represents around 90% of global GNP and 80% of world trade (including intra-EU trade).

The invitation to large emerging market countries to play a greater role in global economic and trade discussions might therefore be genuine. Moreover, it clearly came at a time of desperation: The earlier G-20 summit in Washington in mid-November 2008, when the West acknowledged the need for a broader grouping to tackle the crisis, came a month after the near-collapse of many Western banks.

However, unsurprisingly, the increased importance of the G-20 also accords with the policy goals of the world’s largest economy, the US. “The elevated importance of the G-20 helps to reduce the influence of other OECD countries—most notably European economies—which has long been a goal of the US, which believes the EU is over-represented,” says Rendell.

One obvious alternative to promoting the status of the G-20 could have been simply to add a new member or two, such as China and India, just as the G-7 invited Russia to the top table in 1997. “The G-7/G-8 has never been truly representative, with its four EU members and Canada, so merely adding China would not have made sense,” says Standard Chartered’s Barrett. “Even the G-20 is not perfect. For example, can South Africa really be said to speak for all of sub-Saharan Africa?”

While the barely concealed goal of the US may have been to improve its power dynamic versus other OECD countries, the less overt aim of many Western countries is to create a forum to integrate emerging markets into the global economy.“There are understandable concerns that the West has lost its authority on economic matters, and the liberalization agenda will suffer. The real goal of the G-20 is to prevent the worst deviations from market reform,” says Jones at RBC.

Of course, emerging market leaders such as Brazil, Russia, India and China (BRIC) have their own ideas and once admitted to the top tier of countries are unlikely to be cowed in the company of Western countries (as witnessed by Russia and China’s proposal to use an enhanced Special Drawing Right as a global reserve currency). “The BRICs, in particular, are now in a stronger position to manage the pace of development—in terms of opening their capital account and tariff reform—rather than being forced into a rigid timetable,” says Jones. “The pace of liberalization in emerging markets is unlikely to be as fast in the future as the industrial core would like it to be.”

THE US LOSES ITS LUSTER

Assuming that global power is a zero-sum game, then the increased importance of the G-20—and its emerging market members—must have come at a cost to someone. Clearly, those nations with a place in the G-7/G-8 through a quirk of history rather than economic scale, such as Canada and Italy, will lose some clout. However, more important are the fates of the sole global superpower, the US, and the heir apparent, China.

“If one were to imagine a leadership index, then the US would have peaked in 2000,” says Riccardo Barbieri, head of international economics, global rates and currencies research at Banc of America Securities-Merrill Lynch (BAS-ML). “Even as it has launched two wars and demonstrated its military power, its decline is clearly evident,” he asserts.

Barbieri charts the US decline as starting with the dot-com boom and corporate scandals such as WorldCom. “The 1990s were a golden age for the market economy and the US, driven by the fall of communism, a wave of new technology and a mood of general optimism,” he recalls. “Then it all turned to excess. Issues that should have been addressed to maintain the US leadership position—such as the saving ratio turning negative—were not.”

Instead, there was a decision to accept certain imbalances as a byproduct of a market economy. Moreover, the US took the view that, as long as China and the rest of the world were becoming a market economy, it was winning overall. More obviously, there was a view that the huge expansion in credit was a good thing: The US led by example, with other countries succumbing to a lesser degree.

By this argument, hubris must lead to nemesis. “By 2040 China will have overtaken the US as the world’s largest economy, so the dominant role of the US will inevitably be lost,” says Barrett at Standard Chartered. “The current crisis—which is essentially a debt crisis—is accelerating the transfer of power because the US’s major creditor is China.” Certainly, the adjustments taking place—in terms of risk appetite and leverage—will be hardest felt by the US.

CHINA’S EXPORT PROBLEMS

There remain plenty of skeptics about China’s ability to usurp the US’s unique global role. “The US remains the prime power and the largest economy,” notes RBC’s Jones. “Even if China is growing rapidly, it is not strong enough to act as a locomotive for the global economy. It is sensible that China gets a bigger role in global forums, but the movement of power from the US to China will be an evolutionary change rather than revolutionary.”

The main reason why China might not be able—or want—to affect an overnight change to command the global economy is historical. China has traditionally been an inward-looking country that has never been able to expand globally because of language and structural barriers.

“At the moment, China enjoys disproportionate economic power, but its ability to lead is absent because its economic model, including state control, a currency peg and a massive underemployed rural population, cannot be exported. China does not yet play a leadership role in world economic matters and governance,” explains BAS-ML’s Barbieri. “In reality, the US remains the only game in town; it just needs to amend its model.”

Barrett at Standard Chartered notes that while the Chinese experience is clearly not one that can easily be emulated, its economic model is continuing to become more liberalized. “At the same time, the US is effectively retreating from laissez-faire capitalism as made clear in the assault on the long-held conventions of the debt holders in the capital structure in the Chrysler case and circumventions regarding the bankruptcy code. In reality, the two models are moving towards each other,” he says.

If there are some elements missing for China to take a leadership role in the global economy, therefore there is still a chance of a US comeback, according to Barbieri. “The US must reinvent capitalism—to include elements of improved regulation and planning—this year and next if it is to have a chance to succeed,” he says. “There is some hope of this given that the Obama administration and Congress at least have a more coherent vision.”

Whether or not China overtakes the US to become the largest economy in the world and therefore the greatest political power in the next decade or the next 30 years, its power will continue to grow. The challenge created by the decline of the US and the rise of China is similar to that of the UK and the US during the inter-war period, according to Jacques. “However, the transfer of power is likely to be less orderly than that between the US and the UK because of the affinity between those two nations, which is historically peculiar, and the unique experience of World War I and II and the Cold War,” he notes.

While China and the US have had a stable relationship since the 1970s, there are already signs of volatility creeping into their relationship as a result of the transition described by Jacques. “[US Treasury secretary] Tim Geithner has already accused China of manipulating its currency while China has broken its silence over the problems in the US economy,” he says.

At the heart of the problem is a growing conflict between a rising and a falling power. “It is difficult to imagine it being constrained by the status quo, though hopefully it can be managed without a war,” says Jacques. “Historically, imperial powers are very bad at adjusting to the decline of their empire; the UK is still getting over losing its empire decades later.”

TRANSFERRING POWER

While the long-term game may be in the balance of power between the US and China, in the short term the re-balancing of world power toward China and some other emerging market nations will show itself in the IMF and other global bodies. “The condition of China’s increased contribution to the IMF was reform,” explains Jacques. According to unconfirmed reports, current plans for quota reform in 2011 would raise China’s contribution to the IMF (and therefore its voting rights) to 6.3% of the total compared to 3.72% currently. The increased level would put it second behind the US at 17.09% and ahead of Japan at 6.13%.

In the medium term, more dramatic shifts in the global economic infrastructure may be necessary. “There will be progressive reform of the IMF and the World Bank, but it’s not certain that the architecture of international capitalism will be coterminous with the rise of China,” says Jacques. “Ultimately, new institutions may be required.” Moreover, it is uncertain whether existing bodies such as the WTO will retain their utility or whether the shift toward bilateral trade deals will increase.

Clearly, the nature of how the global economic system operates will change in the coming years, and which countries dominate the world scene will continue to remain fluid. China’s growth could yet be derailed by environmental catastrophe or political insurrection. Nevertheless, while the model of capitalism is clearly under strain, it is not under threat of disappearance. “To paraphrase Winston Churchill, capitalism is the worst economic model apart from all the others that have been tried,” says Standard Chartered’s Barrett. “We may see a new model of globalization emerge, but there is not going to be a wholesale retreat from the existing economic system.”