CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS — FOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Gordon Platt

The euro fell to a four-year low in early June, dropping to within a whisker of its 1999 introductory rate of $1.18, before suddenly bouncing higher in thin trading conditions as the summer doldrums neared. Analysts caution, however, that the European debt crisis has not gone away, and they don’t expect the euro’s recovery to be sustained.

“Given that the root problem of insolvency remains in place for several eurozone countries, we continue to view this euro rally as a corrective move before the next move down,” says Win Thin, senior currency strategist at Brown Brothers Harriman, based in New York.

Pressure on the sovereign bond markets of Greece, Spain and Portugal was reflected in widening yield spreads, even as the euro revived. “The disconnect between the eurozone bond markets and the euro continues,” Thin says. The European Central Bank stepped up its purchases of sovereign bonds of the countries on the periphery of the eurozone.

Meanwhile, given the broad-based foreign buying of US securities over the past two months, the dollar’s value has become far less reliant on foreign demand for long-term US treasuries, according to Michael Woolfolk, senior currency strategist at BNY Mellon, based in New York. “This is a welcome development from the tenuous position seen last year, when foreign investors were consistently selling both US agency and corporate bonds,” Woolfolk says.

The US Treasury released its monthly TICS (Treasury International Capital System) report on June 15. It shows that net portfolio investment into long-term US securities eased to $83.5 billion in April from $140.5 billion in March but beat consensus expectations of $70 billion. “The strong increase in foreign investment in US securities during March and April corresponds with both improving [economic] conditions in the US and deteriorating conditions in Europe,” Woolfolk says. “The TICS data may be reflecting a broader shift among global investors to underweight Europe and overweight other G-7 [Group of Seven industrial nations] economies, including the US,” he says.

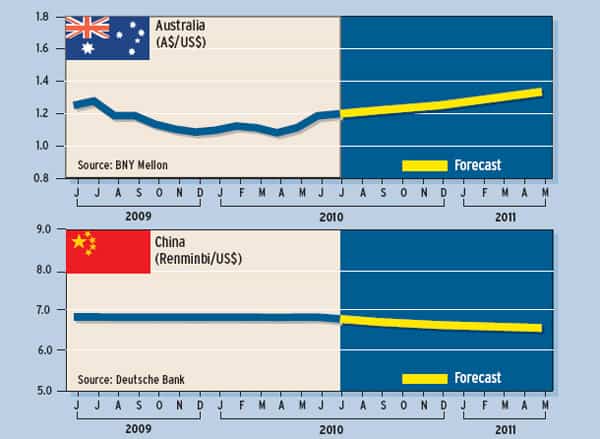

The TICS data indicate that China remains a steadfast buyer of treasuries, averaging $10.3 billion per month in 2009 and $8.2 billion per month in the first four months of 2010, Woolfolk says. “Threats of reserve diversification over the last two years by China and Russia have ended since the breakout of the European sovereign debt crisis and the euro’s 15% decline against the dollar,” he says.

Euro weakness will persist throughout the third quarter of 2010 and into 2011, with the eurozone’s fiscal cutbacks undermining European economic growth and potentially derailing the global economy, according to analysts at Forex.com, a division of GAIN Capital Holdings, which provides online trading services.

“With US fiscal stimulus set to phase out in the second half of 2010, a US slowdown will decelerate the economic rebound and generate another dip in risk sentiment, supporting the dollar as a safe-haven currency and keeping pressure on the euro, the pound and the yen,” says Brian Dolan, chief currency strategist at Forex.com, based in Bedminster, New Jersey. Additional fiscal stimulus by China may reinvigorate the global recovery, he adds.

David Gilmore, partner and economist at Essex, Connecticut–based Foreign Exchange Analytics, says falling stock prices are reason enough to be worried about the economy. “With the US unlikely to export its way to prosperity and the fiscal stimulus nearly exhausted, I don’t have a strong feeling about US fundamentals and risk asset prices and foreign exchange ahead,” Gilmore says. “As we all know by now, the world remains very interconnected, and if things go badly wrong in Greece, Hungary and, in time, core eurozone states like Belgium, the US is impacted,” he adds.

“In the very near term, look for the world to bring pressure to bear on Europe to stop dithering in denial and address its compromised banks and even more compromised states,” Gilmore says.

There has been much discussion in the markets about whether a country such as Greece, or even Germany, could drop out of the eurozone, says Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman. “We have consistently argued against such ideas and, in fact, sometimes have gone one step further, arguing that a new country will join before a country exits,” Chandler says.

Right after September 11, 2001, there was speculation that globalization was going to end, he says. Expanding the World Trade Organization to include China at the end of 2001 sent a strong message of commitment to globalization in the face of terrorism, he says.

“Now, in the face of existential questions about the eurozone, officials are moving in a similar direction,” Chandler says. The European Commission in May endorsed Estonia’s bid to join the eurozone.

Of the 10 countries that joined the European Union in 2004, Estonia is likely to be the fifth to graduate to the European Monetary Union (EMU), following Slovakia, Slovenia, Cyprus and Malta, Chandler says. “It is not the same as Sweden or Denmark joining EMU, but a new member is a new member,” he says. “And at the margins, it supports our contention that it is too early in this great experiment to declare it a failure, despite the current crisis.”

The resilience of the euro in the face of Moody’s Investors Service’s downgrade of Greece’s long-term government bond rating to below investment grade, a weaker-than-expected survey of German economic sentiment and a 2.4% decline in eurozone exports in April was noteworthy, Chandler says. Gains after disappointing news are impressive, he says.

Nonetheless, in relatively quiet markets with investor conviction unusually low, the focus is likely to return to the eurozone’s problems in the short run, according to analysts at Barclays Capital, based in London. Positions of market participants appear to be more neutral, and therefore there may be scope for large positions to be put on against the euro, they say.The UK is one of the countries most vulnerable to euro area stresses, because of both trade links and its own fiscal problems, according to Barclays Capital. The US faces similar problems, it adds, but for now they have been swept under the carpet.

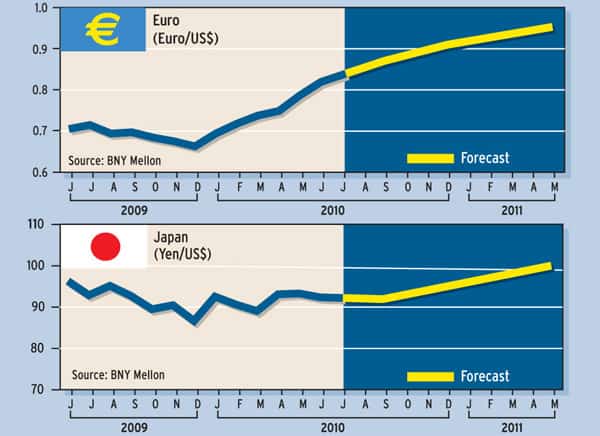

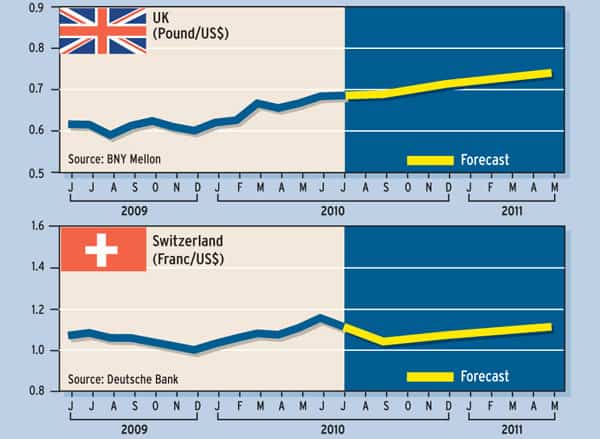

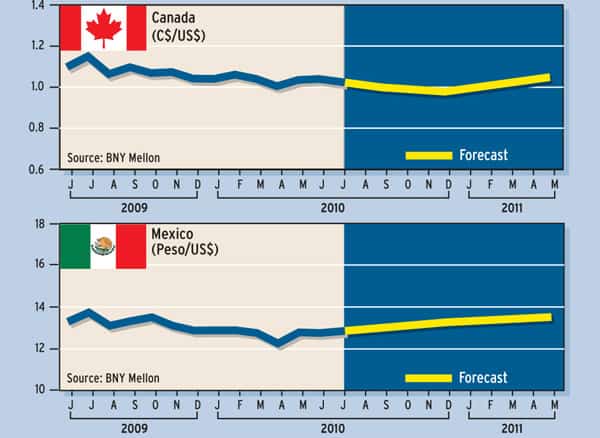

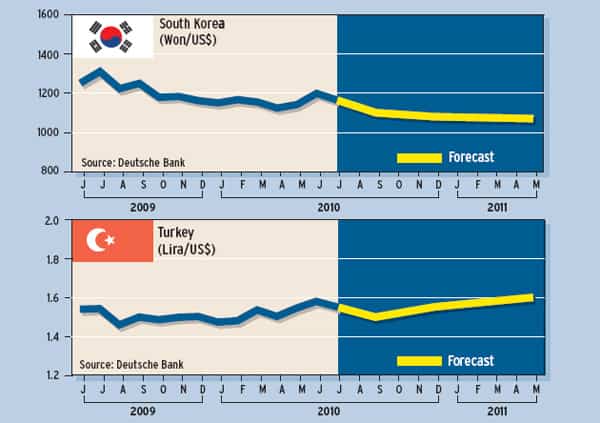

Currency Forecasts