CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS: FOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Gordon Platt

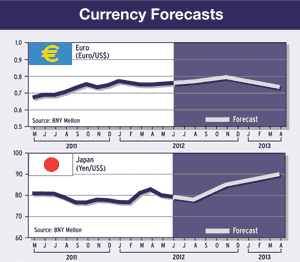

The euro is likely to decline against the dollar in the medium term, due to political uncertainty in Europe and weak economic conditions, analysts say.

“The eurozone debt crisis is entering a dangerous phase,” says Alistair Cotton, senior analyst at Currencies Direct, a global provider of foreign exchange and international payments services out of London. “The Spanish and Italian economies, which are now the focus of the markets, are much larger than Greece and the other peripheral eurozone economies,” he notes.

Over the next six-to-nine months, the euro likely will come under intense pressure, even though it has held up reasonably well throughout the European crises of the past two years, Cotton says. “The euro could be heavily sold, and quite quickly,” he says. “It has taken the authorities two years already, and what have they accomplished?”

The European Central Bank’s long-term refinance operations, or LTRO, have bought some time, but the voters won’t put up with austerity forever, according to Cotton. “It’s almost like a confidence game,” he says. “The authorities are daring market participants to take them on. There might be more liquidity provisions, but they will have to be larger and larger because of the diminishing returns.”

QE3 COULD SAIL

The yen and the dollar will benefit from this situation, as they are two major safe-haven currencies, Cotton says. But while the US economy has an edge over Europe when it comes to economic growth differentials, it may not be as strong as everybody is hoping, he says. Cotton predicts that there will be more quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve over the summer. Otherwise, the US economy could go over a “fiscal cliff” later this year, when the Bush-era tax cuts expire and the failure of Congress to create a deficit-reduction plan triggers automatic cuts to federal programs. “The US dollar is still the reserve currency, and the Fed is still the main player in the market,” Cotton says. “QE3 is coming, and positive US economic data could even lead to a temporary dollar sell-off if it is seen as delaying the stimulus.”

Researchers at Barclays in London say they expect the euro to depreciate further due to weak growth and greater uncertainty in the euro area than in the US. “But we don’t expect a [euro] collapse: Fed policy is crucial and likely to limit the speed of the dollar’s appreciation,” they say.

GRADUAL US RECOVERY

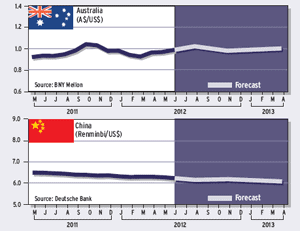

“We expect the US recovery to be gradual but firm, and Chinese growth to land softly at circa 8%,” Barclays says. “Global risk appetite is likely to hold up, given these growth prospects, barring a major ‘accident’ in Europe.”

European developments continue to steal the headlines, but the euro itself remains a difficult currency to trade, according to Barclays. The euro has been confined to a relatively narrow range against the dollar over the past few months, despite generally good news for the US economy and problems escalating in Spain.

Tommy Molloy, a chief dealer at FX Solutions, a foreign exchange broker based in Saddle River, New Jersey, says the potential for an easier monetary policy at the European Central Bank is in the cards. The ECB kept its main interest rate unchanged, as expected, at its meeting in May. At a press conference, ECB president Mario Draghi was noncommittal on the central bank’s future course of action.

Draghi said the ECB would “closely monitor future developments,” a phrase that hinted at additional stimulus measures to boost Europe’s economy, according to Molloy. The eurozone crisis is no closer to solution, however, and the potential for contagion exists, with Spain in focus at the moment,” he says.

HIGHER YIELDS MATTER

The higher bond yields that the market is demanding of Spain and Italy do matter, Molloy says. Italy is the world’s third-largest debtor after the US and Japan, he notes. Spain, which could be the next eurozone country to need help, successfully sold $3.3 billion of debt on May 3, but at much higher interest rates. The Bank of Spain sold three-year bonds at an average yield of 4.04%, up from 2.6% at its previous sale on March 1. Nevertheless, there was solid demand for the bonds at the higher yields, Molloy says.

Meanwhile, the growth of the US economy appears to have run out of steam, he says. “The market is concerned about the robustness of the US economy, which expanded at a 2.2% annual rate in the first quarter,” Molloy says. “There is no worry, however, about a double-dip recession.”

The US employment report for April was disappointing, says Michael Woolfolk, managing director at BNY Mellon Global Markets. Nonfarm payrolls added 115,000 jobs, which was less than a revised estimated gain of 154,000 in March. “The report does have a silver lining—a decline in the unemployment rate to 8.1% in April from 8.2% in March,” Woolfolk says. “However, the headline disappointment increases the likelihood that [Federal Reserve chairman Ben] Bernanke will move forward with QE3 plans later this summer in an attempt to bolster employment growth.”

Inflation and inflation expectations will be secondary considerations for the Fed, now that 10-year Treasury bond yields are back below 2%, Woolfolk says. An earlier rise in 10-year Treasury yields to 2.4% was a concern for policymakers as well as market participants, he says. A break above 2.5% would have forced Bernanke and the Fed to pay closer attention to inflation data. Woolfolk says the Fed chairman can now breathe a sigh of relief and prepare for a QE3 move before US Labor Day on September 3.

Unemployment, not inflation, is the main problem for the US and global economies, says David Gilmore, partner and economist at Foreign Exchange Analytics. “The job of the Fed is not done. Far from it,” he says. “With $1 trillion of QE in place and loads of other programs to support asset prices and liquidity in the banking system, including a zero cost of funds for the banks,” the Fed is not out of ammunition, Gilmore says.

The time has come to shed the inflation worries that dominated monetary policy thinking in the 1980s and 1990s, according to Gilmore. “It is high time to make unemployment the primary focus and hope for a little inflation, rather than swinging the hammer at every policy attempt to support growth,” he says.