CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS: FOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Matt Greco

Things may not look quite as bleak as they did a couple of months ago when there was talk—however irresponsible—of currency wars as trade war by other means, but international currency markets still simmer with potential problems.

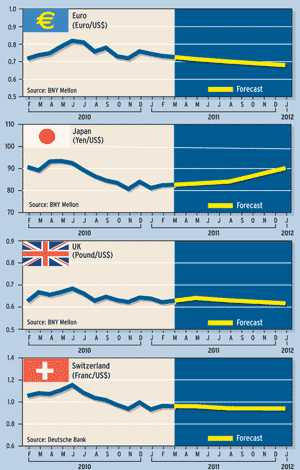

Nevertheless, a number of foreign exchange experts believe 2011 may settle into a year of relative stability with the chief dollar/euro currency exchange trading within a fairly tight range of $1.30 to $1.40 to the euro.

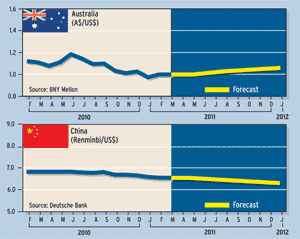

Even the heated debate between the US and China may calm down as China slowly but systematically releases pressure on the yuan, continuing to do so at about a 6% annual rate and with expected inflation effectively adding another 4% appreciation to the Chinese currency, says Michael Woolfolk, managing director at BNY Mellon Global Markets.

International companies with global trade concerns must, of course, continue to hedge their trades according to their bankers’ advice, and those projections just might hold up—at least for the next few months, says David Gilmore, partner and economist at Essex, Connecticut–based Foreign Exchange Analytics. “There’s a lot of dart-throwing in [the forex] world. It’s hard to see beyond one or two quarters, particularly in the post-’08-crisis environment.”

But GDP growth is the great elixir for all problems financial and fiscal, and projections for both the emerging and—especially—the developed world look much better now that fourth-quarter numbers have come in strong, Gilmore says.

Of course, threats still exist, including that of a return of the sovereign debt crisis to the fringe economies of Europe, but for now that situation seems to be under control. The European Central Bank is buying up government debt and has set up a foreign exchange stabilization fund, lent Ireland money and bailed out Greece. All in all, it has made a significant policy response, though Gilmore says that will be sufficient only as long as growth stays relatively strong.

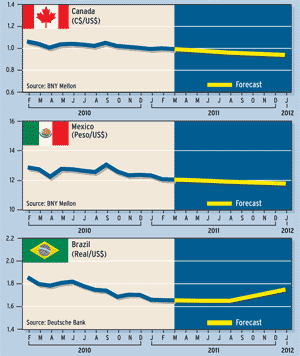

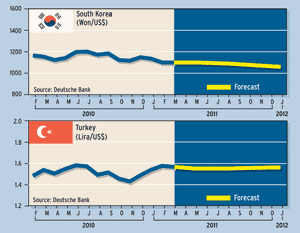

Aside from the potential for another European meltdown there are several other concerns on the radar. One is that emerging markets are raising rates to stymie inflationary concerns and starting to regulate capital inflows to limit the flow of hot money from the carry trade. With US rates near zero, hedge funds and other institutional players are able to borrow money in the US and invest in emerging market currencies and bonds. Brazil, for instance, now has interest rates of about 11% and late last year put a tax on foreign money coming into the market to slow down this flow. Other countries are following suit.

Many countries are blaming the Federal Reserve’s expansionary monetary policies as a major contributing factor to the inflation in commodities—including food and energy—that they are suffering. Woolfolk says other countries’ concerns are unlikely to affect the Fed’s position, while the inflation and subsequent high interest rates make those countries’ currencies more desirable. He notes that since the collapse of Lehman Brothers there has been a negative correlation between the stock market and the dollar. Thus a continued weak dollar, as has been seen against the euro and emerging market currencies, has generally been good for market investors.

But what about all that talk of currency wars and high unemployment in the developed world? Woolfolk believes that although China has been allowing its currency to appreciate at a glacial pace, it has nevertheless strengthened some 25% against the dollar since July of 1995. That strengthening has not led to US job creation, he notes.

Jeffrey Young, managing director at Barclays Capital and head of North American foreign exchange research, notes that the US Treasury last month toned down its rhetoric by not claiming that China is a currency manipulator.

For now, the status quo rules, says Young. None of the major actors quite know how they would like to reform the system, or if they do, they’re not confident that reform would unfold the way they want it to. And talk of an expanded role for a Special Drawing Rights (SDR) system by the International Monetary Fund as an alternative to the dollar as a global reserve currency has died down, he added.

What, though, are the answers to the problems of the current system of international currency exchange? Nicolas Sarkozy, president of France, who now holds the EU presidency, has talked of a need for big changes to the global monetary system, but there is more realism now, Young says. “When you have a fire in the kitchen, you had better deal with that first before you go to your neighbor’s house.”

The net effect, Young says, is that there will be downward pressure on the dollar ameliorated by the support of China and other countries. So businesses should plan accordingly, he says. “There should be no big shift in currency values as a result of policy changes that the US, China or France will get through reforms.”

Unless there is a major crisis, Young doesn’t foresee any major changes. If there were, though, what might such a crisis be? An unexpectedly sharp rise in Chinese inflation could call into question the effectiveness of supporting the dollar, which in turn could force a big adjustment in global exchange rates, Young says. But that would mean interest rates or the currency’s value would have to change by a great deal—something he sees as a remote possibility.

Woolfolk says the US needs to adopt a more direct approach to China by encouraging the Chinese to buy more US imports. The agreement in January whereby China signed on to buy $45 billion of American exports, including several Boeing aircraft, was promising. President Obama is starting to take the right steps toward increased trade, Woolfolk says. “It’s a new year; new rules apply. Obama said it’s the aim of this country to double exports. It’s an admirable goal.”

And the alternative, protectionism, amid renewed talk of currency wars, would be an easy trap for any country to fall into, Woolfolk notes. “It’s one of the seven deadly sins, and there’s very little upside to it except for a short-term fix.” Hopefully, that won’t happen.