WORRIES ABOUT FUNDING DEFICITS COME TO FORE

Deficit financing has replaced interest rates as the driving force in the currency markets, analysts say. As short-term rates converge toward zero, their influence on currency values is dissipating and the focus of market participants is shifting to concerns about where the financing for the growing issuance of government debt will come from.

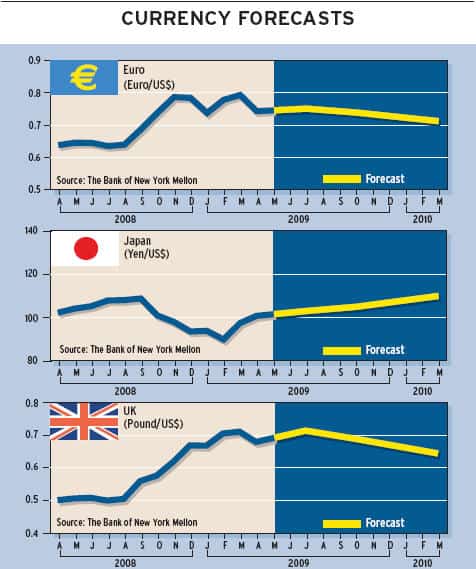

“The scale of funding required to support spending programs in the developed world will substantially outstrip the foreseeable growth in foreign exchange reserves in the year ahead,” says Simon Derrick, a managing director and chief currency strategist at The Bank of New York Mellon. In the longer run, the risk is that the dollar and the British pound could be net losers, given the amount of money they will need to print, he says.

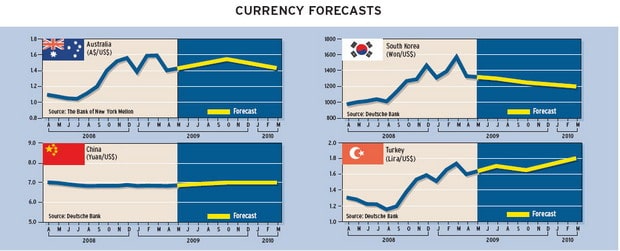

Global foreign exchange reserves fell by about $300 billion in the second half of 2008, according to the International Monetary Fund. Countries such as India and South Korea intervened aggressively in the period by selling dollars to support their currencies as foreign investors pulled capital from these markets.

Meanwhile, the decline in commodity prices, including oil, has likely resulted in a decrease in the pace of reserve accumulation by the major commodity producers, Derrick says. With traditional sources of funding for economic stimulus programs drying up, this begs the question of where the money will come from, he says. China, for one, has already sent an unambiguous message that it is increasingly worried about its exposure to the United States.

“The only viable source of funding until the global economy starts to recover will come from central banks in the form of quantitative easing,” Derrick says. The Group of 20 finance ministers’ meeting revealed a split in opinion between the US and the eurozone over the need for additional fiscal spending, he says. Either the eurozone believes it has done enough already or that it cannot afford to do more, according to Derrick.

At its meeting in London in April, the G-20 agreed to increase IMF funding resources to $750 billion from $250 billion. The IMF will be given another $250 billion in special drawing rights (SDRs) to provide the world’s poorest nations with access to IMF funding without the policy conditions typically demanded as a condition of aid. The G-20 communiqué was silent on the issue of SDRs replacing the dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency.

It appears that the Group of Seven major industrial nations will ultimately get its way in deflecting criticism away from the dollar standard, says Michael Woolfolk, senior currency strategist at The Bank of New York Mellon. “We do not see the greenback realistically challenged for the foreseeable future,” he says. The price paid for this, according to Woolfolk, was an unprecedented amount of G-7 resources directed toward emerging markets through the IMF to stem economic and financial crises and stimulate global trade and investment.

By suggesting the SDR as a reserve currency, China may have been hinting at its own preferred reserve distribution, Woolfolk says. The SDR is a basket of currencies made up of 44% dollars, 34% euros, 11% Japanese yen and 11% British pounds. This could mean that China would like to reduce the proportion of dollars in its reserves from the current 65% to around 44%, Woolfolk says.

With the announcement in April of $300 billion of new currency-swap facilities with central banks in Europe and Japan, the US authorities have substantial new access to foreign currency to sell to the market in intervention or to lend to the banking system, should the need arise.

“This is a significant pro-dollar announcement and is clearly aimed at assuring the largest foreign creditors of the US, like China, that mechanisms are in place that could be used to fund a massive dollar-support operation,” says David Gilmore, economist and partner at Foreign Exchange Analytics, based in Essex, Connecticut.

“In other words, the US monetary authorities are saying that there will be no dollar failure ahead, much as there will be no failure of a major financial institution,” Gilmore says. “There is now a much bigger safety net in place.”

Andrey Vedikhin, CEO of Alpari (UK), a provider of online FX trading services, says that while the euro has benefited from improved equity market sentiment in recent weeks, it likely will decline against the dollar and the British pound in three to six months. Vedikhin says market participants are underestimating the problems the eurozone is facing in dealing with the weak economies of Spain, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Greece.

Meanwhile, the effect of the global credit crunch on Central and Eastern Europe is a problem that could affect everyone, Vedikhin says. “No country should be allowed to fail,” he says. “If one goes down, it will hurt the rest.”

The Alpari foreign exchange trading system was founded in Russia in 1998 at a time when the ruble was falling sharply. A decade later, Russia is facing a similar crisis of confidence in its economy and the ruble, Vedikhin says. “The real economy is declining, and unemployment and under-employment are rising, while the banking system in Russia is saddled with a high and increasing proportion of non-performing loans,” he says. “A number of Russian banks will disappear later this year,” he predicts.

Vedikhin expects the ruble, which was trading in early April at 33 to the dollar, to weaken to more than 40 to the dollar in the next few months, with additional losses to follow.

Alpari expanded to London in 2004 and New York in 2006. It now has 26 offices in seven countries and handles as much as $60 billion in monthly currency transactions for both retail and institutional customers.

Meanwhile, the euro received some temporary support last month from a smaller-than-expected interest rate cut by the European Central Bank. The ECB lowered its main refinancing rate by a quarter point to 1.25%, the lowest level since World War II. This followed a half-point reduction in January.

The Bank of England left its base interest rate unchanged at a record low of 0.5% last month. It also announced that it would continue with quantitative easing to pump more money into the UK economy. The central bank has purchased $38 billion of assets so far.

—Gordon Platt

Source: KDP Investment Advisors