With the presidential referendum finally over, Turkish business wants to see its government get back to probusiness reforms.

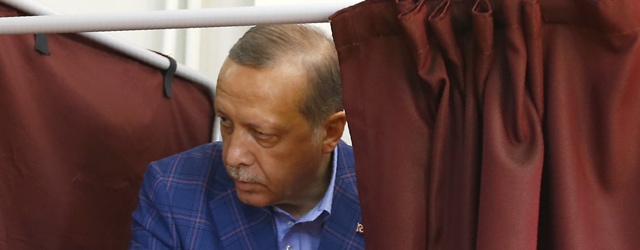

For months, investors and other observers of Turkey’s fevered political scene were fixated on the April 16 referendum on constitutional change. The question of whether the country should retain the parliamentary system set up by founder Kemal Atatürk in the 1920s or move toward a presidential system proved understandably divisive given the magnitude of the stakes and the vastly enhanced powers it would give to President Recep Tayyip Erdoan. The unexpectedly narrow outcome—the Yes side won just 51% to 49%, and Turkey’s three biggest cities all strongly voted No—was greeted with anger by the losing side. They argue that the vast increase in the president’s powers and the fact he could remain in office until 2029 pose very real dangers for Turkish democracy.

However, after five national votes in three years—and further referenda on capital punishment and Turkey’s EU application also possible—most observers would agree that it is surely time to focus on the other challenges facing Turkey. These are considerable.

Domestic security remains a big concern, with risks of further terror attacks in Turkish cities by ISIS or Kurdish nationalists, while the state of emergency that persists at the time of writing—nine months after last July’s coup attempt, which resulted in over 40,000 people detained, according to Amnesty International—continues to damage Turkey’s democracy, image and cohesion.

And then there is the economy, once the calling card of the governing Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalknma Partisi, abbreviated AKP). The pre-2008 heyday of higher growth is long gone, with many investors getting cold feet following the collapse of the lira last year and the corresponding rise in domestic debt. External liabilities of Turkey’s banks have tripled from 2008 and now stand at around $180 billion, and assets—at around $55 billion—cover only a small share of this. All this makes Turkey more than ever dependent on foreign capital inflows to service its debts, which at the national level are compounded by a large current account deficit—some 4.6% of GDP in 2016, according to the OECD—and falling foreign direct investment (FDI). Tourism, a major source of foreign exchange, has been undermined by perceptions Turkey is unsafe, with another poor year predicted for 2017.

Capital flight is also a growing concern. Last year, according to The 2017 Wealth Migration Review by research consultancy New World Wealth, 6,000 Turkish millionaires (people with more than $1 million in assets aside from their principal residence) left the country, a 500% increase from 2015 and a major loss—not just financially: almost all were well-educated, secular professionals. London is a big magnet, with real estate agents reporting an uptick in Turks looking to buy in such prestigious areas as Kensington and Knightsbridge. Meanwhile, unemployment has hit a post–economic crisis high of 12.7%, with the under-26 age group worst hit.

“Economic recovery will be slower than most expect, the lira looks vulnerable, inflation will stay high (around 10%) and monetary policy will remain tight,” says William Jackson of London-based consultancy Capital Economics.

However others are more sanguine. Although inflation hit 11.3% in March—against 9.2% in January—the highest level since 2008 and well above the central bank target of 5%, analysts are confident that a combination of the lira’s stabilization and weak consumer and investment demand will make this a high point.

And there has been good growth news. After a 1.8% contraction in the third quarter of 2016, the economy actually grew much more than expected in the fourth quarter, 3.5%. This means Turkey’s growth for 2016 was 2.9%, slightly below the government target of 3.2% but above what some pessimistic forecasts were suggesting.

Serhat Gurleyen, head of research at Is Yatirim Menkul Degerler, an Istanbul-based brokerage house, anticipates a continuation of the recovery, with GDP rising 2.7% this year and further in 2018.

“Domestic demand will be moderate due to weakness in the labor market, and investment appetite is likely to remain weak due to escalating geopolitical tension and prevailing global uncertainties. But for next year, we foresee economic activity supported with consumption and investment, [boosting] growth to 3.5%,” he says.

THE LONG VIEW

The strong performance of exports since the start of the year—rising 19% year-over-year in March alone, the fastest rate since November 2012, fueled by the cheaper lira and recovery in Turkey’s main export markets—suggests recovery is ongoing. And confidence has been rising from the low at the end of 2016, with the Turkish Statistics Institute’s Economic Confidence Index rising 5% in February and again in March. Gurleyen expects FDI inflows this year to reach $9 billion, with portfolio inflows recovering to $13 billion, as political uncertainty diminishes after the referendum.

Arda Ermut, president of Turkey’s official Investment Support and Promotion Agency (ISPAT), says that given the dramatic developments of 2016—including the attempted coup, numerous terrorist attacks and major geopolitical uncertainty—FDI actually held up well. True, it fell around 25% to roughly $12 billion for the year, but some 60% of that arrived after the July coup attempt.

“When taking FDI decisions, international investors take the long-term view. There is often a lag between decisions being made and investment on the ground,” Ermut says. “It is therefore much too early to evaluate the impact of the crises on investment decisions.”

For its part, Ankara has been doing what it can to shore up confidence and support activity, including last year launching new tax incentives, easing labor regulations and encouraging Turks to save more—Turkey has one of the lowest savings ratios in the emerging-market world, according to the IMF.

One of its most ambitious projects was the creation of a sovereign wealth fund, which was approved last August; some $6 billion to $9 billion of state assets have been transferred to the fund, including government stakes in Turkish Airlines, Turk Telekom and various major banks. The fund will prioritize attracting investment-oriented funds to Turkey, securing low-cost finance for large-scale projects using the public assets as collateral. Ermut says there is confidence the new fund will be able to leverage its resources to draw money from non-state sources, including foreign ones, and provide for investment in Turkey’s strategic assets and help deepen Turkey’s finance sector with new products.

“The Turkish wealth fund will be managed according to internationally accepted governance standards, with highly professional management, transparency and sustainability,” Ermut says, “and with risk management undertaken in full accordance with international risk-management standards.” He adds that the fund will enable the financing of large public projects without adding to national debt.

The government has also announced an investment incentive package worth L140 billion ($37.5 billion) for 23 eastern and southeastern provinces focused on housing, factory, stadium and irrigation projects, to support growth and create employment. So far L23 billion worth of applications have been received, with more expected later this year, according to Turkey’s ministry of Development.

Still, such enticements only work if the underlying proposition is attractive. “Turkey has to deliver the implementation of structural reforms that ease doing business and improve the investment climate,” says Gurleyen. “Enhancing political stability and reducing security concerns will also support FDI inflows.”

And despite downgrades by rating agencies, the financial sector looks healthy.

With the referendum now past, Turkey can hopefully focus on economic and financial issues that many feel have been rather neglected in recent months. In a speech on April 3, the central bank governor, Murat Çetinkaya, spoke of the need for countries—read as Turkey—to establish resilience in the face of future potential economic shocks; among the steps he urged were reforms to boost productivity and competitiveness, flexible labor and product markets and more-efficient social security systems.

“Whilst we appreciate what’s already been done, we think the government should undertake wider reforms to strengthen recent efforts,” says Hüseyin Özkaya, general manager of Odeabank, emphasizing that Turkey’s potential remains considerable, despite the current challenges. “Turkey, the traditional bridge between the West and the East, is one of the world’s most important developing markets.”