COUNTRY REPORT | TURKEY: OVERVIEW

Recent presidential elections saw political continuity and investor appetite maintained in Turkey, but high levels of indebtedness and political divisions may be cause for concern.

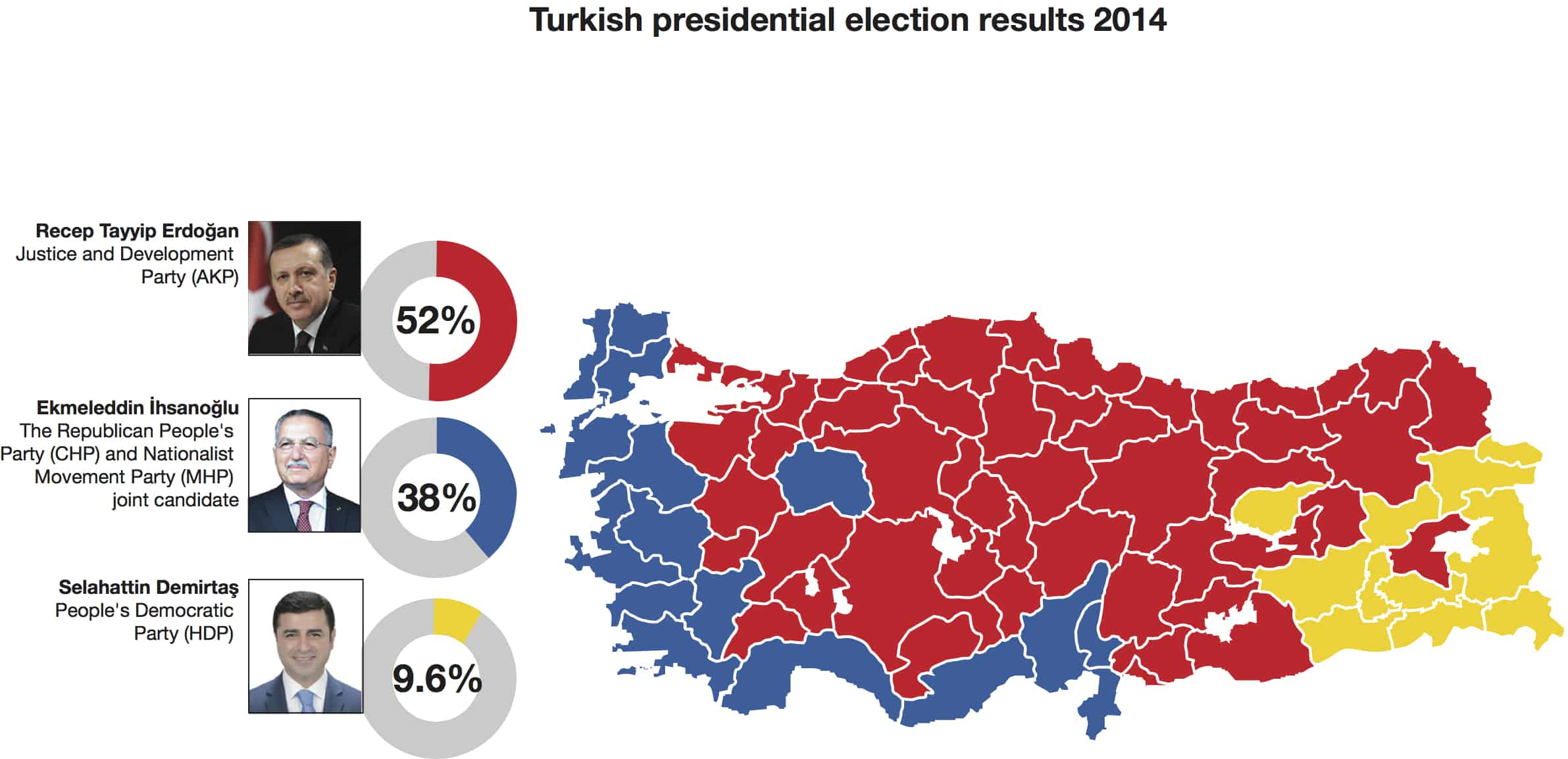

For those who don’t like surprises, there must have been something reassuring about Turkey’s presidential election on August 10. Former prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoan romped to victory in the first round with just under 52% of the vote, well ahead of his main rival Ekmeleddin hsanolu, who received 38%, and Kurdish candidate Selahattin Demirta who polled 9.6%. Indeed, Erdoan’s result was similar to what his Justice and Development Party (AKP) polled in local elections earlier this year, seemingly confirming that Turks remain generally supportive despite political scandals, unrest and the deteriorating situation in neighboring Syria and Iraq, which has raised local tensions and led to a refugee crisis.

The new president’s appointment of a government headed by former foreign minister Ahmet Davutolu also reassured markets by retaining Mehmet imek and Ali Babacan as Finance and Economy ministers and continuing the AKP’s economic policy. Davutolu promised to prioritize reform and Turkey’s EU accession process, as well as to continue rapprochement with the Kurdish minority, seen as even more important given unfolding events in neighboring Iraq. The prime minister is also pressing the idea of a “new Turkey” to coincide with Erdoan’s 2023 ambitions—the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Turkish Republic—in which a new constitution giving more powers to the presidency and continued economic growth will be key elements.

Investors appear reassured. Demand for Turkish debt remains high. Foreign banks are still keen to lend to the country, and the lira has stabilized after some jittery months late last year and early this year, a situation that has reduced upward pressures on interest rates. Moreover, economic growth increased 4.3% in the first quarter, prompting many analysts to raise their full-year growth forecasts from around 2.5% to 3.5%—below the official target of 4% but better than most people predicted at the start of the year. However, second-quarter figures showed GDP growth of just 2.1% (below expectations of 2.8%), which suggests domestic demand is weakening and will increase pressure on the central bank to ease interest rates. Inflation, which is currently around 9.5%, is likely to remain well above target, putting constraints on any expansionary monetary policy and suggesting that foreign direct investment (FDI) is more important than ever to Turkish prosperity.

Ayci, Ispat: We attach the utmost importance to invesments, which contribute to sustainable growth. |

Markovic, EBRD: The biggest risk is changing market sentiment. |

“Turkey is on course to develop despite all the (negative) speculation since the beginning of the year,” said Economy minister Nihat Zeybekci in August, unveiling figures that showed that FDI inflows had risen by 28% to $6.7 billion in the first half of 2014, compared with the first half of 2013, with some 68% of the total now coming from the EU. The biggest beneficiaries were manufacturing, financial services and energy. Turkey is also prioritizing FDI into high-value added areas.

“High technology, high value-added, knowledge-based and skills-intensive industries, which provide high-income jobs, are our priorities; however, we attach the utmost importance to investments, which contribute to sustainable growth,” says lker Ayci, head of Ispat, Turkey’s investment promotion agency.

For this reason, energy has risen to the top of the list, with Ankara keen to reduce its dependence on imports, which have been one of the biggest contributors to the current-account deficit. The government plans to increase the share of renewables—especially wind and solar energy—in total electricity generation to 30% by 2023.

PIPELINE OF OPPORTUNITIES

Turkish investors have also been quite active. Memhet Sami, lead partner for mergers and acquisitions and debt advisory at Deloitte in Istanbul, says local M&A activity in the first half of this year was up on figures for the first half of 2013 (104 deals against 94). Local banks, funds and individuals are eagerly investing in IPOs, especially from recent privatizations in energy and the national lottery.

“Foreign and local businesses are looking for growth and profit; as long as the economic and political stability is here, they will continue to invest,” says Sami pointing to the huge pipeline of opportunities in the government’s ambitious infrastructure investment program, which he says could be worth some $400 billion over the next 15 years.

Sami has also identified a new, growing trend—outbound M&A—with Turkish corporates increasingly looking beyond domestic borders for investment opportunities. Food and agribusiness companies, light manufacturing, tourism and financial services companies have all been active, with many looking beyond the Middle East and North Africa and the CIS countries—traditional expansion areas for Turkish companies—to Europe and even Asia-Pacific. “Turkish companies and banks seem increasingly confident and keen to move beyond traditional comfort zones,” says Sami.

Yet many external observers remain skeptical about the broader economic and political environment. Neil Shearing, chief emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, says the biggest concern is the low savings ratio (around 12%) and the rising debt levels of the past few years (especially consumer debt), which have led to sustained high current-account deficits and inflation. He argues that the authorities have been too

sanguine about growing imbalances and Turkey’s external vulnerabilities and will eventually have no choice but to raise what are currently negative real interest rates (the policy rate is at 8.2%), even though Erdoan and other senior AKP figures remain resolutely opposed to this. “Any attempt to loosen policy will lead to higher inflation and a wider current-account deficit,” Shearing argues.

And then there’s the politics. Erdoan’s election speech saw him promise to be an inclusive figure. It is still early in his term, but with many regarding him as divisive, he will have to work hard to reassure those who think he is acting increasingly authoritarian and seeking to undermine Turkey’s secular traditions. However, his vastly symbolic decision not to live in Ankara’s Çankaya Palace or work at Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul—both have been used by Turkish heads of state since the foundation of modern Turkey in 1923—certainly suggests a break with the past.

DEEP DIVISIONS

Turkey seems an increasingly divided nation—not just between the urban secular elite and supporters of the governing AKP but between supporters of Erdoan and those who prefer former president Abdullah Gül, (whom Erdoan sidelined when he made Davutolu premier). Geographically the election map shows the AKP remains unchallenged within inland Anatolia (except Ankara), along the coast and in Istanbul. However, hsanolu holds sway in Izmir and along the Aegean coastal region, as well as in parts of Istanbul, whereas the southeast remains the stronghold of the Kurdish Democratic Regions Party.

Divisions also reach deep into Turkey’s business community. The head of Müsiad, the association representing Muslim businessmen, said Erdoan’s presidential victory “reflected popular support for the continuation of a peaceful, trustworthy and stable environment.” By contrast, Haluk Dinçer, president of Sabanci’s retail and insurance group and of the secular Tüsiad industry and business association, stressed the need for an end to the “current polarized and segregated environment, which…could threaten democracy and development.” Officials, however, describe the tense political environment as natural, given the circumstances. “Three important elections during a relatively short time easily gives way to heated debates in any democracy, especially in a country like Turkey, where so much has been achieved in so little time in such a volatile region,” says Ispat’s Ayci.

And the investing community seems prepared to give Turkey the benefit of the doubt, at least until next June’s general elections, when longer-term questions—about the AKP’s new economics team and strategy (Babacan and other ministers have a three-term limit to their tenure) and about whether it has secured a mandate sufficient to change the constitution—will come to the fore.

“Over the longer term a risk to growth may come from sub-optimal decisions being made, for example in failing to reduce regional imbalances or enhance energy security; in the short, the biggest risk is changing market sentiment, due to the unwinding of quantitative easing by the US Federal Reserve or perceived weakening of regulatory independence, which may lead to a rise in Turkey’s risk premium,” says Bojan Markovic, lead economist for the EBRD in Istanbul.

Currently, however, there is little sign of such risks emerging. Continued growth, the welcome downward trend in the current-account deficit—most analysts expect the figure for full-year 2014 to be around 6%, down from 7.8% last year—and resilient FDI and investment have led many investors to look at Turkey with fresh eyes.

Another positive is changing perceptions regarding Turkey’s debt growth. Earlier this year ratings agency Fitch warned that “foreign liabilities had increased as loan demand outpaced growth.” Janine Dow, senior director, financial institutions, Fitch Ratings, says Turkish loan growth slowed to just 7% in the first half of this year compared with 20% in the first half of 2013. Growth in household debt has also slowed.

Foreign funds have moved away from Russia, following its invasion of Ukraine, and Turkey is regarded as a more attractive and predictable destination. “Turkey is attracting considerable interest from the three main types of investor (retail, mutual funds and pension funds) because the key investment drivers—a positive economic outlook and political stability—are in place,” says Didem Gordon, CEO of the emerging-markets investment management group Ashmore Group in Istanbul. n

GFmag.com Data Summary: Turkey

Central Bank: Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

International Reserves |

$87.9 billion |

||

|

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) |

$827.209 billion * |

||

|

Real GDP Growth |

2011 8.8% |

2012 2.2% |

2013 4.3%* |

|

GDP Per Capita—Current Prices |

$10,815.457* |

||

|

GDP—Composition By Sector* |

agriculture: 8.9% |

industry: 27.3% |

services: 63.8% |

|

Inflation |

2011 6.5% |

2012 8.9% |

2013 7.5% |

|

Public Debt (general government |

2011 39.1% |

2012 36.2% |

2013 35.8% |

|

Government Bond Ratings |

Standard & Poor’s BB+ |

Moody’s Ba3 |

Moody’s Outlook NEG |

|

FDI Inflows |

2009 $8,411 million |

2010 $9,038 million |

2011 $15,876 million |

*Estimate

Source: GFMag.com Country Economic Reports, CIA, IMF, Unctad