Public Private Partnerships are sweeping the globe, but in the country where they have been most used PPPs remain deeply controversial.

In late September last year, US Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan flew to London for an unusual task. He cut the ribbon on the newly made-over UK Treasury building, a stones throw from the Houses of Parliament.

Behind the elaborate neo-Italian faade, more than eight miles of internal walling had been removed to create a spanking new open-plan environment in the building where economist John Maynard Keynes drew up the post-World War II plans that helped create the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

But this was no ordinary public sector makeover.The 170 million project involved a privately funded consortium of construction and service companies leasing, refurbishing and maintaining the building for 35 years. The Treasury pays 14 million a year to its new landlords. Excess floor space will be let to external clients and profits shared.Delivered on time but within budget, this has been a model of how a successful private finance initiative project should work, said UK chancellor Gordon Brown at the opening.

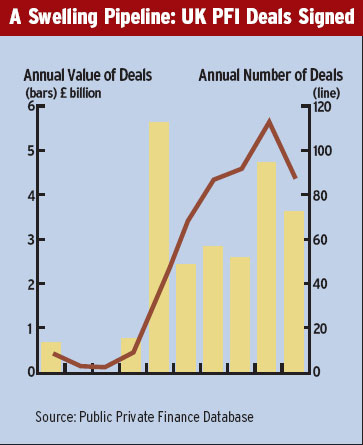

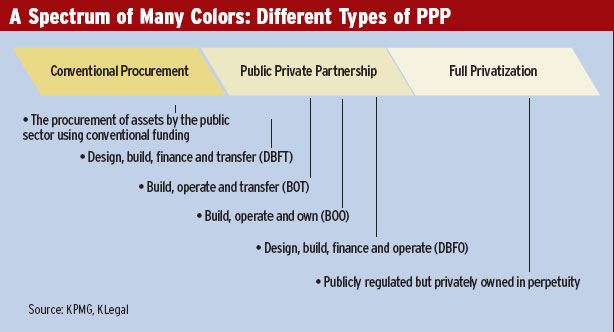

Set up by a Conservative government in 1982, the Private Finance Initiative (PFI) was reinvented and reinvigorated by Tony Blairs incoming center-left government in 1997 as Public Private Partnerships (PPP). PPPs cover a grab-bag of procurement models from privatizations to simply hiring outside contractors.With PFI the private sector builds the project and raises finance in the capital markets; other PPPs are paid for directly by the public sector (see table, page 24). In all its incarnations, its fast gathering steam.Viewed as a way of financing a much-needed wave of investment in public services, there is now little of UK public life that has not been touched by this new means of procuring and financing goods and services.

Alongside a wave of new hospitals, prisons and refurbished schools, the 25 billion-plus of new PPP projects under way or finished range from new kennels for Armed Forces animals tomost controversially of alla 3.5 billion contract to upgrade and maintain part of the Tube, the subway system that Londoners love to hate.

The PFI/PPP process is revolutionizing the delivery of better public services, faster and to a consistently high quality,argues Tim Stone, international chairman of PPP advisory services at professional services group KPMG in London.

To be sure, the United Kingdom is not the onlyand certainly not the firstcountry to use private money to deliver public goods. The French state granted a private sector company a concession to build the Canal du Midi as far back as 1514.And provision of education and healthcare in countries such as the United States, for example, is a bewildering mosaic of the private and the public.

But rarely has a shift from public procurement to private taken place on such a scale as in the UK. And there are clear signs that shift is being mirrored elsewhere.

Procurement, English Style

In late December 2002 the Mexican federal government announced that 20 billion pesos ($1.8 billion) would be made available for English-style PPPs in 2003. Eduardo Salo, a spokesperson in the office of President Vicente Fox, says the schemes, involving schools, prisons and hospitals, will be a priority this year.

Theres a host of reasons why countries as far apart as South Africa and Italy have created task forces to push forward PPPs, or why Japan and Quebec have passed legislation allowing schemes to proceed. Some of those reasons are good, some less so.

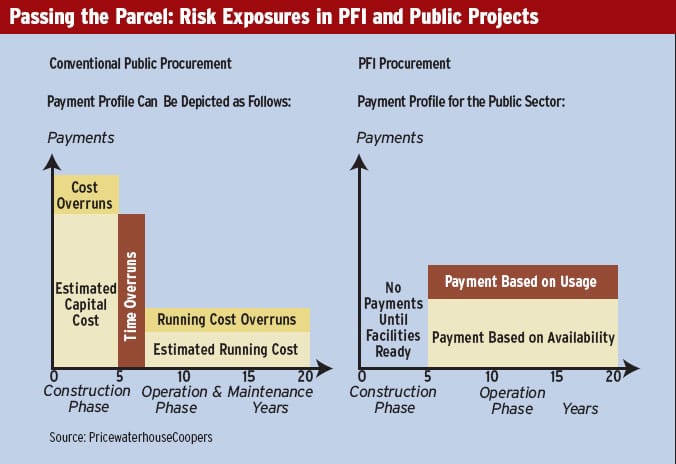

The need to deliver infrastructure improvements in the face of budgetary constraints is driving countries in central and Eastern Europe looking to join the European Union, says Stephen Harris, head of the international division at IFSL, a London-based trade association that acts as an entrept for UK financial services expertise. Places like Hong Kong are more interested in the efficiencies of the process, he adds. Others argue that risks of cost and time overruns once borne by the public secsector are now transferred to the providers.

More than 40 countries, regional governments and agencies have sought to use UK experience to kick-start programs, says Harris, ranging from the organizing committee for the 2008 Beijing Olympics to the German state of North-Rhine Westphalia.

They are hoping to meet the private sector head on. Increasingly realizing that winning lucrative construction and service contracts means playing the PPP game, builders, cleaners, healthcare providers are all stumping up equity stakes for projects, taking on risks they might once have passed onto the client, and in the most extreme cases, reinventing themselves.

But the transition from builder to landlord requires reaching into previously untapped sources of finance such as the bond markets. So far, theyre finding willing lenders. Stretching to match long-term liabilities such as pensions and guaranteed annuity contracts, asset managers are edging into the PFI market, advancing debt to project sponsors in

the expectation of stable, long-term flows. Sometimes backed by external guarante

es, bond investors in the UK have financed assets ranging from roads through hospitals to prisons.

Thats the kind of wish list that attracts elected politicians, and the lengthening queue of finance officials wishing to learn from the UK experiment is eloquent testimony to the size of the stakes at play.The problem is, it is an experiment. Evidence of the success or otherwise of PPP in the UK is mixed, at best. Putting the funding element of the contract for the new Treasury building opened by Greenspan out for tender saved the taxpayer 13 million, or 7% of the lifetime cost of the deal, according to John Bourn, head of the National Audit Office, a key government watchdog. The same body calculated that a PFI deal for a new British embassy in Berlin saved little money but successfully transferred overrun risks to a consortium involving German construction company Bilfinger+Berger and US facilities manager Johnson Controls.

Mixed Results

But for every success story, theres a tale of woe.The UK army is relying on a new $3 billion fleet of Apache attackhelicopters to give it some of the offensive punch of its US counterpart.It will get that firepower,but not yet.Up to half the helicopters will be stuck in storage for as long as four years after the finish of a $1 billion PFI contract awarded to helicopter builders GKN Westland and Boeing to train 144 pilots was put back from April 2004 to February 2007. New PFI hospitals have hit the headlines for all the wrong reasons with incidences of sewage cascading through clinical areas, wards either too hot or too cold, and, worst of all, bed shortages right from opening.

Put at least some of that down to the public sector not exactly knowing what it wanted. The greater clarity in the purchase negotiations distills contentious issues that were fudged earlier, say PFI advocates. But its clear that potential problems with PFIs go beyond teething pains.

Theres plenty of evidence that PFI is not working in schools and hospitals, says Allyson Pollock, a professor of health policy at University College, London. She argues that high initial subsidies have masked the cost of PFI deals and that public health authorities have tied themselves into long-term, expensive contracts that will siphon off cash from other areas such as clinical care.

Those arguments have added to widespread antipathy toward PPPs among a UK populace already skeptical over the benefits of private participation in public service provision. Episodes such as the effective renationalization of track operator Railtrack and the woes of the partprivatized National Air Traffic Services have bolstered the argument that for essential services, at least, the public sector will always have to pick up the bill if a private operator fails to deliver.

In the public mind, PPPs are now a bad thing, admits IFSLs Harris. In the 1992 general election, for example, an independent candidate won the English Midlands constituency of Kidderminster by campaigning against a PFI hospital project.Its politics that have obscured the true benefits of PPPs, say private sector advocates.

The quality of the public-private debate has frankly been appalling, says Digby Jones, director-general of the Confederation of British Industry, a UK business association. We need to get away from confrontational language and focus the discussion on delivering quality services to the tax-paying public. In reality,though,thats partly down to the strange reluctance of the UK government to set out adequately why it is so committed to the PFI.While ministers and officials now stress value for money, for five years they pushed the argument that PPPs were the only way the government could afford to make up for three decades of neglect of the countrys public sector.Thats a totally bogus argument, says Paul Maltby, a research fellow at the Institute of Public Policy Research, a left-of-center think tank that has produced some of the most closely watched work on PPPs. He argues that chancellor Gordon Brown could easily have financed the investment from the public purse without breaking his own golden rules for prudent finance.

|

The Netherlands. One of the furthest advanced of the European countries, the Netherlands has set up a Kenniscentrum, or knowledge center in the Ministry of Finance. Despite that, progress has been a little disappointing, according to Kenniscentrum member Stephen Raggett. Flagship project is the 1.2 billion project to build and maintain a stretch of high-speed rail line between Amsterdam and the Dutch border, won by a consortium including Siemens of Germany and the hometown BAM. Split into building, maintenance and train operation, the project has got off to a poor start, with cost overruns on the conventionally financed track build. The next, true PPP part of the project is likely to work more smoothly, says Raggett. He points out that the greater decentralization of power in countries like the Netherlands can make projects harder to get off the ground than in the relatively centralized UK. The State of Victoria. This southern Australian state of 4.5 million people is leading the introduction of private sector involvement in public sector projects, with five deals worth A$670 million already signed, A$500 million in the market and A$2 billion under consideration. Key projects include a statewide high-speed rail upgrade and a new film and TV studio complex in Melbournes old docklands. Italy. With state budgets at bursting pointthe deficit stands near 3% of GDPand large investment needs, this country is a natural for PPPs. Italy has a law and a special unit of the Italian Treasurythe UFP. The 61.5 million Tecnoborgo waste-to-energy project at Piacenza, near Milan, has been hailed as a true PPP as it involves a joint partnership between a municipal waste company and a subsidiary of Vivendi Environnment. Still, the checkered history of public sector works in Italy instills caution among project sponsors and advisers alike. Source:Global Finance |

Right Thinking, Right Actions

Getting the reasons right for using the private route is important, say people who have watched the PFI process closely in the UK. These are just some of the arguments advanced for using the private sector: Projects are more likely to get built on time and on budget. Sometimes: 18 out of the first 31 PFI hospitals in the UKs National Health Service were lateon average by 12 months. Still, there are few disasters yet to match the late 1990s Jubilee Line extension to Londons subwayby some measures the most expensive track in the world mile-for-mileor the new Scottish parliament in Edinburgh, which may come in three years late and 10 times over budget. Both were built by private contractors under a conventional public sector model.

Services can be delivered better and cheaper. The IPPRs Paul Maltby argues that introducing alternative forms of provision in areas such as the Prison Service has improved the overall standard of service. Critics worry that cheaper services can only be at the expense of reducing staff costs.That equation is critical to the economics of PPPs. Jon Sussex, an associate director in the Office of Health Economics, points out that hospitals and other health services are typically labor- rather than capital- intensive. Staff accounts for 60% of hospital costs; depreciation and interest costs total just 8%.Thats important as PPP techniques move from big-ticket construction projects into long-term service provision such as health and education.Its relatively easy to contract for building a new road, says Maltby.Its much more difficult to specify everything that should happen in a big hospital over the next 30 years.

PPPs can deliver investment that the public sector cannot provide. That depends. For cash-stretched countries, the private sector can finance capital programs that couldnt be accommodated on the government balance sheetbut only if theyre not subject to overarching public sector accounting constraints. European accounts watchdog Eurostat is likely to judge a PPP project as not counting toward the allimportant General Government Balance only if there is significant transfer of risk to the private sector.Thats likely to complicate matters for existing EU countries bumping against 3% deficit constraintsItaly, Portugal and Germanyas well as accession countries seeking to bring infrastructure up to scratch.Where theres a dedicated service charge paid by usersroad tolls, for examplePPP can keep the cost off the balance sheet. Elsewhere, the bill will eventually have to be met in the form of payments to the private sector.

The overall cost will be cheaper. The most controversial arena, with the battle lines obscured by conflicting criteria. Because the PFI is the only game in town for key sectors such as schools and hospitals in the UK, there is widespread unease that the figures have been skewed by public sector managers desperate to get projects off the ground.What is clear is that private financing is typically more expensive than government borrowing, by between 1% and 3%, according to most UK estimates. Even with cheaper refinancing factored in, that makes for a considerable extra cost over the lifetime of, say, a 30-year deal.

In January the UKs Audit Commission published a report on the first PFI schools and in a widely publicized conclusion found they hadnt been built quicker, better or, crucially, cheaper than schools built by the public sector over the same period.

But the government argues that doesnt take into account the risk of overrunwhich would be borne by the builders under PFI, rather than drawing on the public purse.In every case, PFI was judged to offer a saving once an estimate of the value of risk transferred to the private sector was included, argued the Audit Commission.

That argument has won converts around the globe. The difference between the private and public sectors is that private sector capital markets explicitly price in the risk of a project into its source of finance, says Ian Little, secretary at the Department of Treasury and Finance in Victoria,Australia.Taxpayers implicitly subsidize the cost of a project by bearing the risk of cost overruns, time delays or performance failures, which are not priced into the government borrowing rate.

With the case for PPPs as yet unproven, the UK governments decision to plump wholeheartedly for that route is rooted in a fear of a return to the bad old days of untrammeled public spending, say observers.And while that commitment has spawned the largest body of PPP case studies, it is perhaps near-neighbor Ireland that provides a more useful road map for countries seeking to enrich the mixture of infrastructure investment.

|

Contractors Have to Work for PFI Money

A license to print money at the public expense, is a widespread view of PFI in the UK. If only, would be the likely response of some of the companies that have been involved in the PFI in recent years. During 2002 the dream of a sound long-term revenue stream turned sour for a growing list of companies in the UK, sounding a warning bell for construction and services companies hoping to benefit from a worldwide switch to private sector provision. The key ingredients of a noxious cocktail that poisoned for some what had once looked so promising a business prospect: thin project margins; high bid-ding costs; and concerns over how to account for projects on a companys bal-ance sheet. Few took a more spectacular tumble than Amey, a once-dowdy UK construction company that sought to transform itself into a business services support group. In March last year the company wrote down the value of its current project bids, restating its 2001 figures to a pre-tax loss of 18.3 mil-lion, instead of the previously reported 55 million profit. The UK Accounting Standards Board said last year that bid costs should be written off, rather than being brought onto the balance sheet as an asset. As Global Finance went to press, Amey was set to sell its PFI investments for a knockdown price of 40 million. The share prices of other companies involved in the PFI, such as construction company WS Atkins and business services company Serco, have also underperformed the market. If much of that sluggishness reflects worry over accounting treatment for PFI projects, it also recognizes the fact of declining margins in a competitive, maturing market. Analysts have traditionally worked on a rule-of-thumb rate of return of around 15% for equity investors in PFI projects. Contractors on the new London subway contracts are working on planned margins of 19%. Generally, however, greater competition for projects and increased claw back of refinancing profits have shaved at least a couple of percentage points off internal rates of return, say analysts. Some early PFI deals garnered contractors windfall profits; once they had completed the more risky building phase of the contract, they refinanced deals at much tighter margins. In 1999 the consortium building a new prison at Fazakerly in North West England pocketed 10.9 million from a refinancing, effectively getting the prison for free. The public sector now writes in provisions guaranteeing claw back of 50% of any refinancing profits, though its less likely to achieve its aim of recover-ing 30% of refinancing profits on existing deals. All of this puts a heightened focus on the task of managing risks for con-tractors sponsoring PFI projects. With PFI the only game in town in certain sectors, builders have been forced to become equity investors if they wish to stand a chance of winning top contracts. Thats worrying on a number of counts, and not just for shareholders. From our perspective, consortia are too often dominated by financiers and builders, says John Pierce, secretary at the treasury of New South Wales, Australia, arguing that the government interacts with them only during the project development and construction phases. Pierce says he would prefer a stronger presence from the infrastructure operator, with which the govern-ment typically has a 20- or 30-year relationship. It also makes it harder for companies to control the risks building up their balance sheets. That may be partially addressed by a secondary market that enables companies to sell on exposures in projects to more willing investors. In April 2002 Innisfree, the leading UK equity investor in PFI projects, launched a fund dedicated to investing in secondary PFI projects. This January US life assurer John Hancock committed 50 million to the fund, bringing it up to 150 million.

|

Taking a Different View

With economic growth averaging 8% a year in the late 1990s, Irelands infrastructure was creaking fit to bust. Tourist postcards depicting a flock of sheep and the legend Irish traffic jam had become a bad joke as roads in and around Dublin and Cork seized up.

In 1998 the government introduced a 52 billion N a t i o n a l Development Plan aimed at reducing the infrastructure deficit. PPPs were conceived of as partbut only partof that process.

It is important to remember that under the governments approach, and in contrast to the PFI in the UK, PPPs in Ireland include Design, Build and Operate projects where there never has been any prospect of private finance, said finance minister Eddie McCreevy to the Irish parliament in November 2002.McCreevy was introducing a bill to set up a National Development Finance Agency from 2003. Managed by the National Treasury Management Agency, the body that runs the Irish national debt, the NDFA has the power to set up specialpurpose companies to raise private finance for projects, but only where this is likely to be cheaper than raising money through the public sector.

That more pragmatic approach is one many observers of the UK scene argue could more usefully be followed elsewhere on the globe. There are a million types of Public Private Partnerships,says Paul Maltby at the IPPR. There is no reason why the default model should be the PFI.

Mark Johnson is the editor of Global Finance.

Email: mark@gfinance.co.uk

By Mark Johnson