Saudi Arabia is the Gulf Cooperation Council’s largest economy, but major economic, political and social challenges threaten the kingdom’s immediate economic future. Reducing its dependence on oil and gas is now a case of when, not if.

Saudi Arabia is at an economic and political crossroads. The rise of the youthful deputy crown prince Mohammad bin Salman has raised concerns as to the level of change within the ruling Al Saud family. And while Saudi Arabia seems eager to embrace greater economic openness with the rest of the world, there is no escaping the long-simmering political, social and economic tensions that exist within the country.

The most pressing concern for the Saudi government is the need to diversify the nation’s economy away from oil. Diversification has been on the to-do list for some time, but it has taken on a greater sense of urgency recently with the dramatic fall in oil prices to below $27 a barrel and its impact on the Saudi economy, which relies on the oil and gas sector for approximately 90% of its revenues.

The kingdom’s finances are the biggest casualty from the drop in oil prices. On December 28, Saudi Arabia declared a 2015 budget deficit of $97.9 billion—its largest ever, according to Fitch Ratings. Within hours it issued a royal decree raising some gasoline prices by 66%. The fall in oil prices has forced Saudi Arabia’s policymakers to slash public spending and confront politically sensitive cash handouts that underpin the government’s social contract with the nation.

If low oil prices were its only problem, Saudi Arabia might muddle through. It has amassed substantial reserves and has low levels of government debt—around 5.8% of GDP at the end of 2015, according to the Ministry of Finance (MoF). There are also encouraging signs the government wants to liberalize the economy. In January, Mohammad bin Salman gave the strongest hint yet that the privatization of Saudi Aramco, reputedly the world’s most valuable company, is on the agenda.

Nevertheless, Saudi Arabia faces a toxic mix of political and economic problems. At the top of the list is the diplomatic standoff with Iran, its rival’s return to global oil markets and concerns over the kingdom’s foreign policy. During last November’s OPEC meeting Saudi Arabia again declined to cut oil production. The trouble is, the drive to stave off US shale oil could take the economy to the brink.

OIL AND BEYOND

The economic challeges facing Riyadh were highlighted when the MoF announced the kingdom’s 2016 budget in late December. At $224 billion, spending is 13.8% percent lower than in 2015. The budget statement left little doubt as to the government’s mood—it will review subsidies, reduce public-sector wages and consider excise taxes, including VAT. The latter measure is in line with what other GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) members are doing. Tackling subsides is a gamble, and the government is betting popular support won’t erode.

Not only did Riyadh raise gasoline prices; it also increased gas, diesel, kerosene, electricity and water prices. BoA Merrill Lynch Global Research estimates the natural-gas price hike on petrochemical firms and the gasoline and diesel price hike could add $2.2 billion and $3.8 billion, respectively, to central government revenues, but they are hardly game changers.

In a statement following the budget announcement, Jadwa Research, the research arm of the Saudi-based investment bank, said that it expects both revenues and expenditures in 2016 to be above the budgeted level but said the differential will be smaller as the government becomes more prudent in its spending. Jaap Meijer, managing director and head of equity research at Arqaam Capital, a specialist emerging-markets investment bank, expects to see greater fiscal discipline by the Saudi government in 2016.

Even so, oil prices are expected to remain a drag on the economy. The lack of economic diversification renders Saudi Arabia uniquely vulnerable to a protracted period of low prices.

The IMF says a sustained decline in oil prices will impact growth and hit the banking sector. In November, Standard & Poor’s warned that banks in Saudi Arabia face heightened economic risks and weaker operating conditions. The assessment follows S&P’s downgrade of Saudi Arabia’s sovereign rating to A+/A-1 from AA-/A-1+ at the end of October. Iran’s return to global oil markets could further dampen oil prices by between 5% and 10%, the IMF says. The fund predicts the kingdom’s GDP will grow by 1.2% in 2016, compared with growth of more than 3% just two years ago.

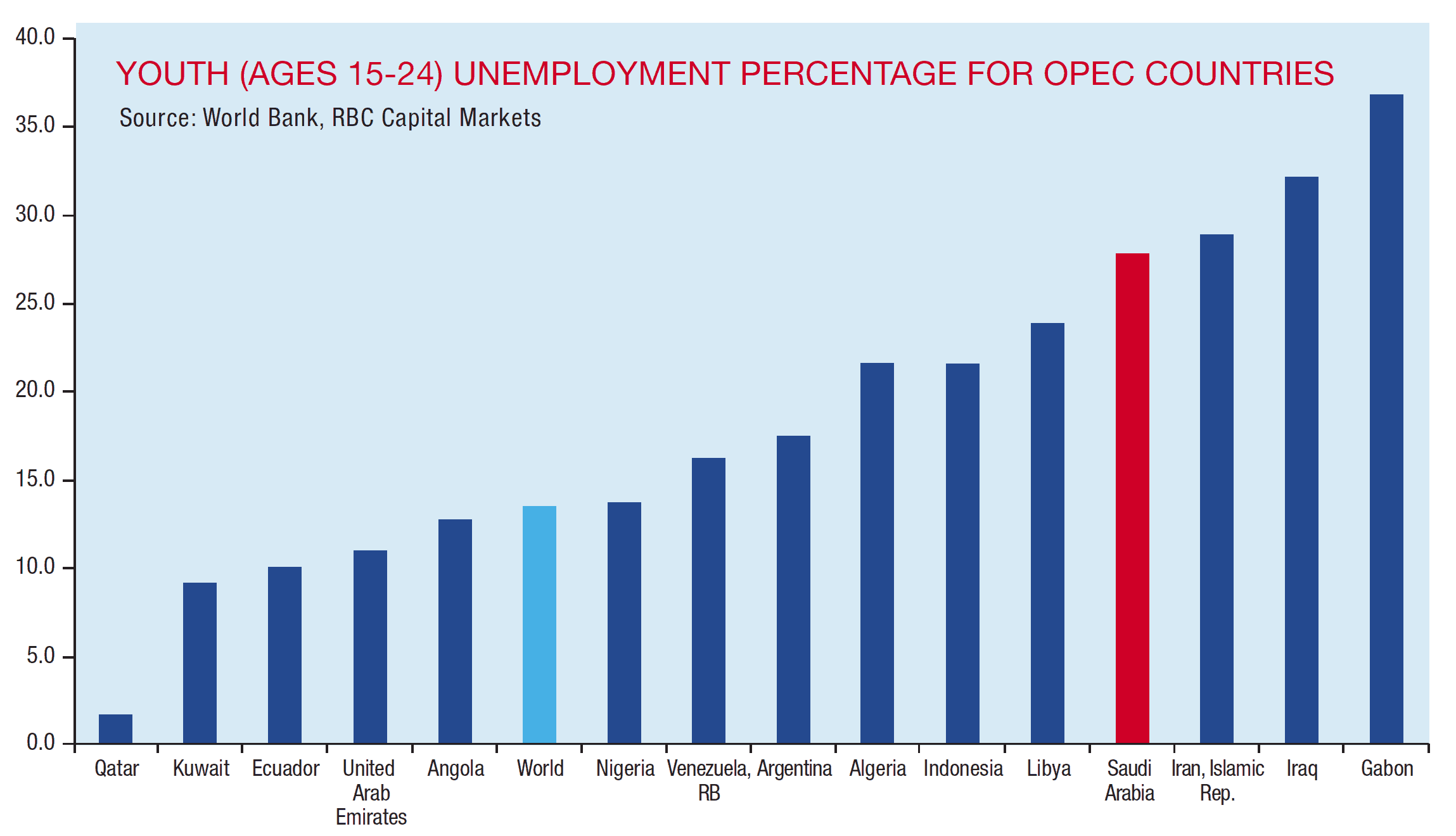

Time is no longer on Saudi Arabia’s side. It must take bold steps to diversify its economy. In December the McKinsey Global Institute published a report entitled Saudi Arabia Beyond Oil: The Investment and Productivity Transformation. MGI calculates that even if the kingdom introduces such policy changes as a budget freeze or immigration curbs, unemployment, which was 5.7% in the second quarter of 2015, will rise rapidly, household income will fall, and the government’s fiscal position will deteriorate sharply. Youth unemployment in Saudi Arabia remains one of the most pressing policy issues (see chart). The unemployment rate for ages 15 to 24 in Saudi Arabia is 29%.

However, MGI says there is a real opportunity to transform the economy and create up to six million new jobs by 2030. Such a transformation has a price, though; it would require a staggering $4 trillion in investment, MGI estimates. The institute identifies eight sectors—mining and metals, petrochemicals, manufacturing, retail and wholesale trade, tourism and hospitality, healthcare, finance and construction—that have the potential to generate more than 60% of growth.

Whether the kingdom has the capability to undergo such a change remains to be seen, but Mohammad bin Salman appears determined to overhaul the economy. According to a Riyadh- based analyst who spoke on condition of anonymity, it is a question of timing: “It would have been better if economic reforms had been implemented when [oil] prices were at $100 a barrel—at less than $40 it is going to be hard.” That view is supported by the deterioration in FX reserves held by the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority. At the end of November, reserves fell to $635.5 billion, down from $740.4 billion a year earlier.

Uncertainty over the economy is also rattling foreign exchange markets. Although the Saudi Arabian riyal is pegged to the US dollar at around 3.75 riyals, there is mounting speculation Riyadh could be forced to devalue. In January, one-year dollar/riyal forwards spiked to 16-year highs after Saudi Arabia cut diplomatic relations with Iran and markets reacted to the kingdom’s swelling budget deficit.

London-based research firm Capital Economics says currency devaluation would be a last resort. The government has earmarked several privatizations that would partially offset the fall in oil prices, and it could turn to international bond markets in 2016, albeit for the first time.

Many in the business community also remain optimistic about the resilience of the economy. “[Budget] spending is reasonable, especially with the current oil price and the fact that the country has been at war in the last 10 months,” says Ibraheem Al-Jardan, senior business development manager at Riyadh-based investment firm Dayim Holdings.

IT’S NOT JUST THE ECONOMY, STUPID

Saudi Arabia has been able to shake off economic shocks before, but the difference this time is that the kingdom’s assertive foreign policy is being called into question. What concerns analysts is that all roads increasingly trace back to Mohammad bin Salman. Even in the Gulf’s lexicon of grand titles, his breadth of influence—deputy crown prince, second deputy prime minister, minister of Defense, secretary general of the Royal Court and head of the kingdom’s Council of Economic and Development Affairs—is formidable.

When King Salman acceded to the throne in January 2015, he swept through royal ranks, dismissing former crown prince Muqrin, placing his son, Mohammad bin Salman, as second in line to the throne. Skipping a generation has fueled unease in the royal family, according to analysts. “The degree of change within the ruling family and the rapidity of Mohammed bin Salman’s rise over the past year has reinforced a sense of bewilderment in many Saudi watchers,who find themselves struggling to make sense of where the drivers and objectives of policy lie,” says Kristian Ulrichsen, a fellow for the Middle East at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. The move, Ulrichsen says, has worried observers.

In an unusual public statement in December, Germany’s intelligence agency, the BND, expressed concern the kingdom was becoming impulsive in its foreign policy. Saudi Arabia’s execution of 47 so-called terrorists in early January, including a

high-profile Shiite cleric, had political ramifications that ricocheted across the Middle East, not least with Saudi Arabia’s Shiite neighbor Iran, where the public responded to the executions by attacking Saudi diplomatic missions. Saudi Arabia severed diplomatic ties with Iran in January, adding a further dimension to an already edgy regional geopolitical environment.

Diplomatic tensions aside, the key to the kingdom’s economic fortunes will be the speed with which it is able to implement reforms. Last year the Saudi Capital Market Authority allowed foreign financial institutions to buy and sell stocks on the Tadawul, the Saudi stock exchange, for the first time. There has been little feedback on the take-up by foreign investors since the change in regulation. The IMF has urged Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries to deepen capital markets as a way to strengthen their economies. If Saudi Arabia does tap international bond markets this year, it might be an appropriate time to develop a secondary market in local currency debt.

With a nominal GDP of around $644 billion, Saudi Arabia is still the Gulf’s largest economy by far. But investors will have to weigh risk more carefully than they have ever done before.

GFmag.com Data Summary: Saudi Arabia

Central Bank: Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

International Reserves |

$744.4 billion |

||

|

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) |

$632.1 billion* |

||

|

Real GDP Growth |

2013 |

2014 |

2015* |

|

GDP Per Capita—Current Prices |

$20,138* |

||

|

GDP—Composition By Sector* |

agriculture: |

industry: |

services: |

|

Inflation |

2013 |

2014 |

2015* |

|

Public Debt (general government |

2013 |

2014 |

2015* |

|

Government Bond Ratings (foreign currency) |

Standard & Poor’s |

Moody’s |

Moody’s Outlook |

|

FDI Inflows |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

* Estimates

Source: GFMag.com Country Economic Reports