The Dollar’s Decline

A weak dollar may be beneficial to the US in the short term, but it is undermining the dollar’s long-term status as the de facto global currency.

By Laurence Neville

One of the rocks on which the global economy has been founded since World War II is a strong US dollar. As a projection of the United States’ political, military and financial might, it has been all-powerful for more than half a century. As a means of exchange for goods and services the world over, including all commodities and much international trade, it has seemed unassailable. Now, that dominance is coming to an end for financial, economic and political reasons.

One of the rocks on which the global economy has been founded since World War II is a strong US dollar. As a projection of the United States’ political, military and financial might, it has been all-powerful for more than half a century. As a means of exchange for goods and services the world over, including all commodities and much international trade, it has seemed unassailable. Now, that dominance is coming to an end for financial, economic and political reasons.

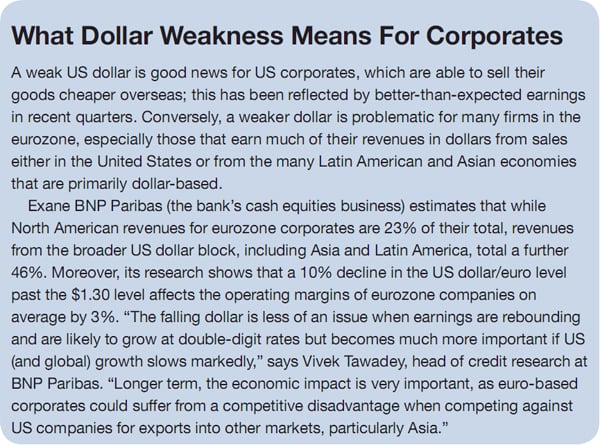

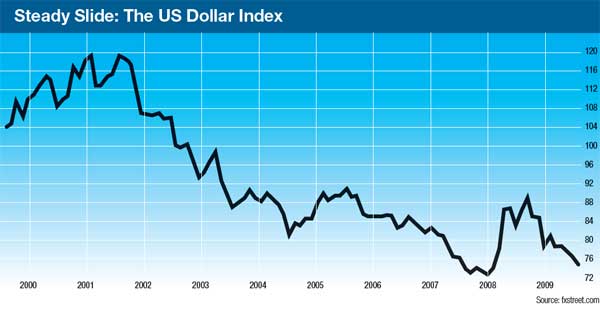

Over the past year, the US dollar/euro exchange rate has declined from $1.25 to $1.50. BNP Paribas economists expect that by spring or early summer 2010 the dollar/ euro rate could touch $1.55—a fall of more than 3% in little more than six months. To be sure, part of the reason for the current weakness of the dollar—and its negative outlook over the next two years—is a normal cyclical phenomenon regarding rate expectations. Australia and Norway have already begun tightening policy, and market participants are looking for the next major-economy central bank to make a move. “Other [central banks] are set to follow early this year,” says Adam Cole, global head of FX strategy at RBC Capital Markets in London.

The widespread assumption is that the US Federal Reserve will be among the last central banks to follow suit and raise rates because its economy, along with that of the United Kingdom, is the most structurally challenged and therefore needs as much monetary largesse as possible. “Moreover, along with the UK, the US will have to reverse its quantitative easing policy before it embarks on rates rises, which are therefore some way off,” says Cole.

The expected disparity in rate movements around the world means that the dollar is going to be unattractive on a yield basis and helps to explain some of its weakness. However, there are a number of other longer-term phenomena that explain why the dollar can be expected to remain weak. While the financial and economic crisis has exacerbated and highlighted a number of these trends, many have been evident for years.

US Creditworthiness

One of the main ingredients among the cocktail of negative influences on the value of the dollar is the perceived creditworthiness—or lack of it—of the US government, which is currently running a deficit of $12 trillion. The markets are prepared to cut the US a lot of slack because it is the world’s largest economy and remains the issuer of the world’s reserve currency. That makes it easier for the government to sell bonds and support itself in the short term. “Nevertheless, the current situation does raise concerns, and that is reflected in the dollar’s value,” says RBC’s Cole.

“In the short term, the US has given itself an adrenalin shot of ultra-loose monetary and fiscal policy that is unsustainable and which has not fully solved many of the problems facing the domestic economy,” says Peter Rosenstreich, chief market analyst at foreign exchange broker ACM in Geneva. “Although there have been some signs of economic recovery, the housing market remains in trouble, with defaults of up to 15% of the entire market currently predicted.”

Similarly, in the labor market, although there has been some stabilization, jobs are still being shed and not enough quality jobs added. “These factors will undermine the ability of the US to grow, as the consumer fails to show up to the recovery, which will in turn limit its ability to tackle its structural weaknesses,” notes Rosenstreich. “The $12 trillion government deficit cannot be tackled without a stable and resilient underlying growth story. It’s a scary picture that can do nothing but undermine the dollar.”

A Diminishing Role

Another negative influence on the value of the dollar is a gradual process: It is suffering from a diminishing role as a reserve currency. Excluding the Chinese central bank, which does not report its holdings to the IMF, around 40% of global reserves are in dollars compared to 55% a decade ago, with the difference lost to a range of currencies such as the euro and sterling, according to Cole at RBC. “That decline in importance as a reserve currency is more than just symbolic,” he says. “Although the flows generated by central bank sales have limited impact, to some extent they do dictate demand for a currency.”

When Chinese central bank holdings are taken into account, the future appears even bleaker for the dollar. Standard Chartered estimates that at the end of 2008 the Chinese central bank held 82% of its reserves in US dollar assets. “That heavily overweight position is no longer appropriate given concerns about the stability of the dollar following quantitative easing,” says Robert Minikin, senior FX strategist at Standard Chartered in London. “Changing direction will take time, but there is already evidence that China is adding to gold holdings, for example, as an alternative to the dollar.”

Despite its secrecy, it is impossible to believe that China does not recognize the benefits of diversification as an investment strategy and therefore impossible to believe that it will continue to buy US debt endlessly. “Of course, in the short term such a move would be counterproductive, but it is wrong to rule out the possibility of a reduction in Chinese holdings of dollar debt,” says Rosenstreich at ACM. “When it occurs,it will have significant consequences for the dollar and could unleash a downward spiral.”

|

|

Minikin: “As the US role dwindles, the |

|

|

Rosenstreich: “Ultra-loose monetary |

Crucially, any weakening of the US dollar requires the world to have an alternative currency. Five years ago there were no clear alternatives; now there are. It is notable that the Canadian, New Zealand, Australian and Swiss economies did not collapse during the economic crisis. While none of these is a clear single alternative reserve currency, as a basket they offer a convincing alternative. “Moreover, the current speed with which the BRIC countries are continuing to grow is unlikely to slow,” says Rosenstreich. “By the end of the next decade, it is likely that China and Brazil will be robust enough to provide the certainty required for central bank treasurers to begin to shift some of their reserves to the real and yuan.”

Cole agrees that the renminbi will eventually become a reserve currency but says that 10 years is too short a time horizon. “It would need to become convertible first and then become widely accepted globally before becoming a reserve currency, and that’s more likely to take 20 or 30 years,” he says. Moreover, deep and liquid financial markets are needed to support a currency if it is to be a reserve currency; currently only the euro comes close to the dollar in that respect.

Trade and Commodities

While the dollar might be becoming less important as a reserve currency, the actions of central banks are insignificant compared to global trade volumes— much of which is conducted in the US currency. The convention of using the dollar to price trade and commodities is a reflection of the US economy’s dominant position following World War II— just as sterling played a similar role in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “As the US role dwindles, the dollar’s importance will be pared back,” says Minikin at Standard Chartered.

Minikin believes that it is already clear that there is a steady whittling away of the dollar’s status as the currency of trade. “There have already been efforts to boost the role of the euro and, to a lesser extent, the renminbi,” he says. “There are trade corridors developing—within Asia, for example—which don’t include the US, and therefore it no longer makes sense to denominate everything in dollars.”

However, while there have been discussions between, for example, the Chinese and commodity producers in the Middle East and Brazil about using alternatives to the dollar, any substantial shift to de-dollarize trade and commodities— possibly using IMF Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) as an alternative— is a long way off. “If that is China’s goal, then it stands a good chance of succeeding,” says RBC’s Cole. “However, that is a 30-year project, given the changes in payments and settlement infrastructure required.”

Despite these challenges, the dollar’s fate looks sealed, with no resurgence likely in the long term. Undoubtedly, there will be bouts of recovery and corrections during periods of high risk aversion, such as during concerns about Dubai in late November. Similarly, a strong performance by US equities could prompt inflows that bolster the position of the dollar. “However, overall, while it is wrong to say that the US dollar will never be able to get back its position of strength globally,” says Rosenstreich at ACM, “it is extremely unlikely in the foreseeable future.”