LIBYA: OPENING UP

By Justin Keay

As its economy slowly becomes more open, Libya is attracting the attention of a wider range of potential investors than just adventurous oil companies.

In the old days of the Soviet Union, sovietologists would gauge reform prospects by studying the Kremlin lineup at military parades to see how close key individuals stood to the general secretary. In much the same way, Libya watchers try to determine head of state Muammar al-Qadhafi’s intentions by judging how much prominence his sons get in the national media and in the running of the country. If the modernizing 38-year-old Saif al-Islam seems in the ascendant, reform prospects look good. If his younger, more conservative brother Moatassem-Billah, Libya’s national security adviser, seems more prominent, the assumption is that old statist tendencies are reasserting themselves.

The reality, of course, is much more complex. Despite rumors to the contrary, Qadhafi doesn’t seem to favor either son over the other as his successor and seems happy to listen to both. This means the country is as hard to read as ever, even if it is relatively easy to take some of Qadhafi’s wilder suggestions—such as his calls for the abolition of the state and the nationalization of oil companies operating in Libya—with a large pinch of salt.

Richard Dalton, a former British ambassador to Libya and a fellow at international policy think tank Chatham House, argues that the liberalization that accompanied Libya’s return to the international fold from 1999 onward and the 2005 resumption of relations with the US is continuing, with the country moving from a planned to a mixed economy. “Yes, there is an ongoing clash between those who want to move faster and those who want to slow down, but there’s no disagreement over the direction: All agree liberalization is the way to go,” he says.

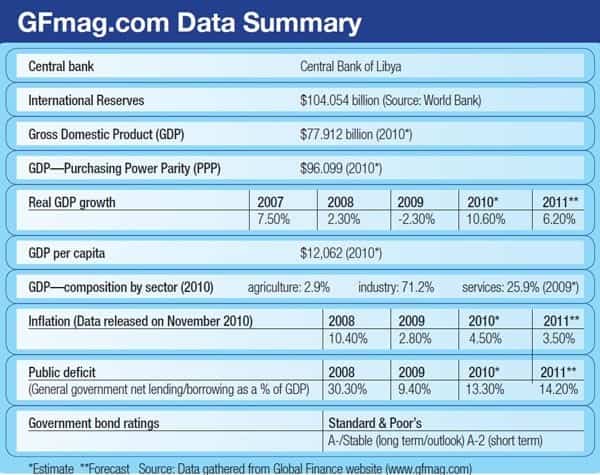

The IMF certainly believes so. Its latest report, published on October 28, commends the authorities on their efforts to boost the private sector by passing a series of liberalizing laws. Projecting that 2010’s GDP would grow 10% on the back of sharply increased oil production (which accounts for 70% of GDP and 95% of export earnings), against a decline of 1.6% last year, it concludes Libya is determined to diversify to create viable employment opportunities for the growing labor force. The IMF was equally positive regarding medium-term prospects: “Libya’s economic growth and financial position are expected to strengthen as a result of higher oil receipts and investment in the oil sector, the upgrading of infrastructure, the implementation of reforms and the continued interest of foreign investors.”

What kinds of investors are being attracted? Dalton says the typical company or bank that invests in Libya would be one accustomed to working in difficult, unpredictable environments where decision-making can be erratic. “This is a very good market for companies with an appetite for being in such markets,” he says. “If they can put up with the disadvantages, there is clearly a lot of money to be made.”

Obviously, the main focus to date has been on the hydrocarbon sector, notably oil, where the authorities are keen to step up production from the current level of some 2 million barrels per day (bpd) to 2.5 million by 2015 and 3 million after that. Unsurprisingly, international oil companies have been falling over themselves to sign energy agreements with Libya, with such companies as Occidental, ENI, Total, BP and Repsol all engaged to some degree.

However, the US and other Western countries are dipping their toes in other areas too. The first major US trade mission to Libya, which took place last year, was heavily oversubscribed, with an eclectic mix that included Boeing and Electrolux. Twenty-five companies participated, although 75 companies applied, which gives some measure of the interest.

And opportunities are growing. Privatization is proceeding, albeit slowly, and Tripoli’s three-year-old stock market expects to hit the milestone of having 25 companies listed soon, with many more joining over the coming year, including cell phone companies Al Madar and Libyana. The total market capitalization of firms on the stock exchange is expected to exceed $1.3 billion by the end of this year, although the bourse still remains closed to non-Libyans. IPOs are expected in the banking and steel industries, while other investment opportunities will be driven largely by the ambitious infrastructure projects: Roads, technical colleges, housing and even whole new suburbs are planned to boost employment prospects among the 6 million-strong population and alleviate housing shortages. So far, this focus on the non-energy sector seems to be working: In 2009 non-oil GDP grew 6%, and the IMF expects Libya to have posted a rise of 7% last year.

The bank sector has also seen considerable, meaningful reform, with regulation remaining conservative and conducted along international lines. The 2008 merger of Gumhouria and Al Ummah into Libya’s largest bank—now simply called Gumhouria—was a vital transformational step, with the profitable state-owned bank issuing new products and aggressively seeking depositors in its 150 branches. An IPO took place in 2009 as a first step toward the bank’s being privatized totally. BNP Paribas has had a stake in state-owned Sahara Bank since 2007 with management control and the right to increase its stake to 51%; it is drawing on BNP Paribas’s international expertise in order to introduce new products for retail and commercial customers. Meanwhile Jordan-based Arab Bank has held 19% of Libya’s Wahda Bank since 2008, while the granting of a license in August 2010 to Italy’s UniCredit marks the first time a Western bank has been licensed to operate fully within Libya.

However, for some, the fact that UniCredit was the only Western bank green-lighted for a license, despite widespread expectation that HSBC and Standard Chartered would also get one, is symptomatic of the erratic decision-making in Tripoli. Skeptics point to the fact that although investor-friendly laws have been drafted, their implementation seems to be taking rather longer than expected.

There are other causes for concern too. Tourism is expanding but very slowly, with long-term growth restrained by the absolute ban on alcohol. This suggests a low-volume future with most visitors being either adventure travelers or people attracted by the rich archaeological heritage, including the famous Roman city of Leptis Magna. Meanwhile, many of the building projects currently under way in Tripoli, Benghazi and elsewhere have ground to a halt, their funding interrupted because of disputes with investors.

And despite all the ballyhoo, the energy sector hasn’t quite delivered what was hoped: Recent oil and gas finds have been underwhelming, and the government’s ambivalence about giving international oil companies free rein has hardly helped speed exploration or production. Consequently, some analysts say the IMF projections are too optimistic. “The way things stand, there’s no way the economy [in 2010 can have grown] by 10%. Our forecast is 3.3% GDP growth, fueled mainly by capital spending on infrastructure,” says Rory Fyfe, Libya specialist at the Economist Intelligence Unit. He argues that OPEC constraints and declining real demand for Libyan energy will mean growth will be around 3.7% this year and 3.9% in 2012.

That said, how many new, relatively wealthy but largely untapped markets just off the coast of Europe are there these days? Tom Cook of the London-based Middle East Association led a trade mission of some 33 companies to Libya in October and says much of the apparent ambivalence to foreign investment reflects suspicion of the outside world’s motives. “I would describe the current situation as a tentative opening up,” he says. “Libyans know the worth of what they have, but they are cautious about how to return value, not least because many lack understanding about how international finance and commerce work.” He adds, however, that the Libyan business community is very open and keen to do business.

This suggests that for companies seeking new horizons, Libya—despite its small population and erratic politics—will remain something of a magnet.