CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS: FOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Gordon Platt

The tax deal reached between President Obama and the opposition Republican Party could boost US economic growth to around 3% in 2011, economists forecast. The improved economic outlook and rising bond yields are expected to lift the dollar further against the euro, which is still being dragged down by Europe’s sovereign debt crisis, analysts say.

“The current phase of dollar stabilization is gaining vital support in the form of rising 10-year US treasury yields,” says Ashraf Laidi, chief market strategist at CMC Markets, based in London. “While it can be argued that rising US yields tend to increase the debt burden of the US government (which would hurt the dollar), the current run-up [in yields] is the result of growth expectations, with the US economy showing generally better-than-expected economic figures.”

The recent data, with the notable exception of the weak nonfarm payrolls in November, raise the possibility that the Federal Reserve may not complete its $600 billion in asset purchases announced under QE2, the second phase of quantitative easing, Laidi says.

Raghav Subbarao, foreign exchange strategist at Barclays Capital, based in London, says the weak US employment data in November were a reminder that, while the euro has its fair share of problems, anemic growth and QE2 are negatives for the dollar. The euro and the dollar are engaged in an “ugly” contest, rather than a beauty contest, Subbarao says.

The rise of 39,000 in US nonfarm payrolls in November followed a revised increase of 172,000 jobs in October and was far below the consensus forecast for a gain of 150,000 jobs. The percentage of unemployed, discouraged and marginally attached workers has remained around the 11% level for more than a year, says Michael Woolfolk, managing director at BNY Mellon Global Markets. “The concern here is that an increasing number of workers are becoming structurally unemployed,” Woolfolk says.

Over the near term the euro will remain under downward pressure, because the problems of the peripheral eurozone countries remain unresolved, says Paul Robinson, a director and currency strategist at Barclays Capital. “Prospects for the euro remain at the center of investors’ concerns,” he says. “It has faced by far the most serious crisis in its brief history in 2010, and going into 2011 important unanswered questions remain.”

However, despite all the problems facing the euro area, the single currency has not collapsed, Robinson notes. The average value of the euro from its inception to the end of 2009 was $1.18.

The dollar and the euro, in effect, are playmates on a teeter-totter. Both currencies will underperform the market in stages in 2011, Robinson says. “There are likely to be periods where the speed of weakening of one of the currencies almost forces the other to strengthen.”

Barclays Capital’s core view is that the current peripheral-country problems of the eurozone will be contained but that there are risks for a weaker euro in the short term. In the longer term, the pressures on the dollar may be greater, it says. “We are fairly upbeat about US growth prospects, which would be consistent with higher yields,” Robinson says. “However … the unemployment rate is unlikely to fall back quickly.”

Another major issue for the dollar is the US current account deficit, which is forecast to increase from 3.6% of gross domestic product in 2010 to 5.2% of GDP in 2012, making it one of the few G20 economies to expect a significant increase of its deficit over that period, Robinson says.

“The Fed is continuing to loosen policy, and the recent agreement between the parties to extend both the Bush tax cuts and long-term unemployment benefits and to cut payroll taxes means that the US is almost alone [among economies with a large government deficit] in delaying strong action on bringing about fiscal consolidation,” he says. “In the longer run, currencies adjust to facilitate a move toward external balance, and this is likely to be a major negative for the dollar over the next few years.”

David Gilmore, partner and economist at Essex, Connecticutbased Foreign Exchange Analytics, says, “In due course, when the US government can’t borrow nearly unlimited amounts at very low nominal and real interest rates, the history books will surely talk about a generation squandered.”

Not even the world’s largest economy, with the privilege of being the world’s reserve currency, can play “kick the can down the road” indefinitely before markets say, “Enough!” according to Gilmore. “Not even when the Federal Reserve is buying treasuries as fast as the government can issue them,” he adds.

Nowhere in Washington is anyone talking about tax hikes, which are critical to balancing the budget, Gilmore says. “Anyone who thinks it can be done from discretionary spending [reductions] and entitlement cuts is dreaming,” he says. “Markets won’t stand for this nonsense, especially foreign markets which fund the US deficits.”

The recent rise in US yields stemmed from the prospective changes in US fiscal policy, with markets worried about the increasing supply of US treasuries as a result, says Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman, based in New York.

Investors, including China, who are caught between QE2 and widening spreads in peripheral Europe, have found Japanese treasury bills a good place to park their funds for a short while, Chandler says. The European financial crisis, high anxiety from the Korean peninsula and Chinese rate-hike fears are encouraging some profit-taking on emerging market exposures, he says.

“The contrast between the fiscal austerity in Europe and the extension of the tax cuts in the US has rarely been starker,” Chandler notes. Nevertheless, the widening crisis in Europe has been a major driver in the capital markets, he says. “Risks of contagion appear to be spreading to the core,” he adds. “Officials have failed to get ahead of the curve of market expectations in preemptive funding of Portugal, if not Spain.” Perhaps the biggest problem is a lack of appreciation of the significance of confidence in the functioning of a modern credit economy, Chandler suggests. “European officials have squandered this confidence, and like toothpaste coming out of a tube, it is difficult to put it back in.”

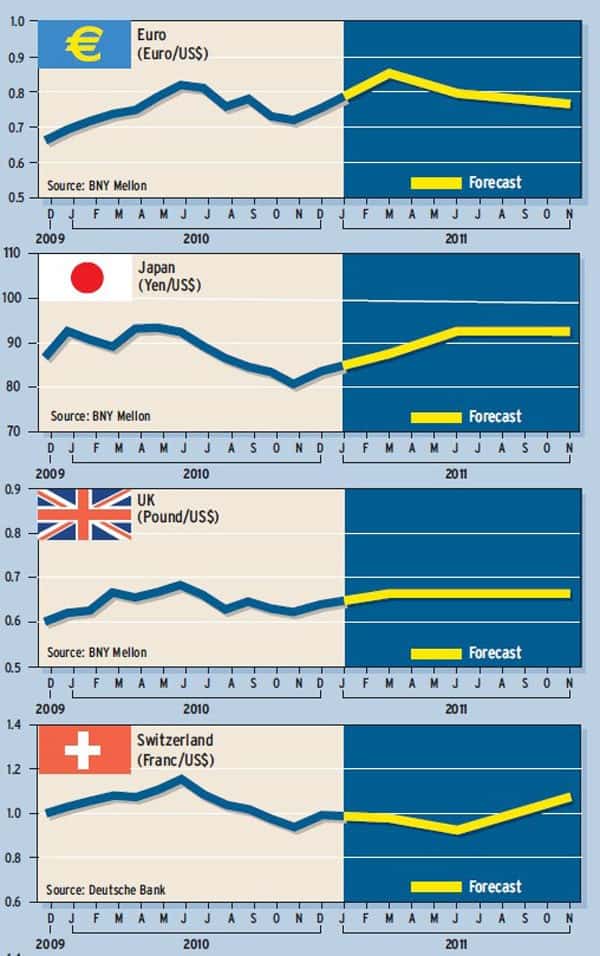

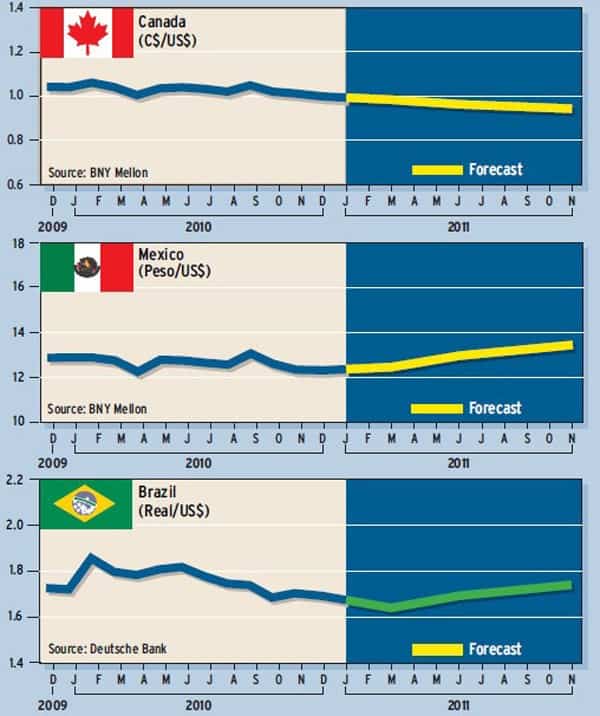

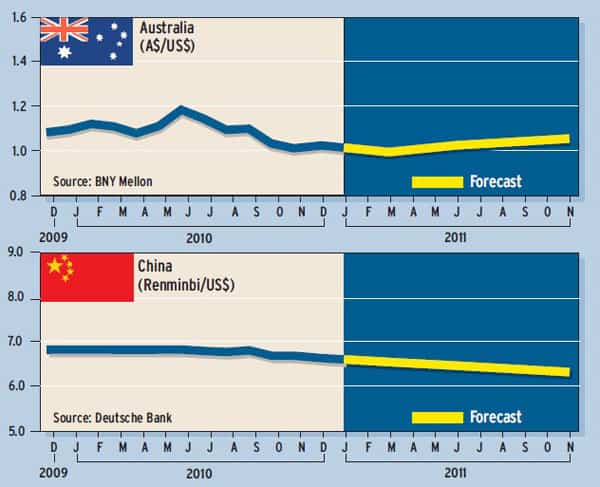

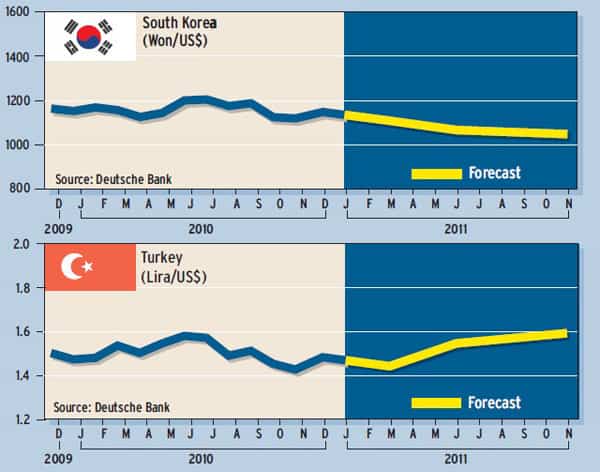

Currency forecasts