As the regional powerhouse restructures and tackles debt problems, neighboring nations are feeling the impact.

China’s debt burden has worried investors for a long time, not only because of its size but also because of its pervasiveness throughout the mainland economy. New estimates of the size of overall debt do nothing to assuage those concerns—if anything they heighten the urgency with which China must embrace reforms. In a May report, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) estimated China’s overall debt burden had risen to a staggering 295% of GDP in the first quarter of 2016. The proximate state-owned enterprise debt in particular is heaping pressure on Beijing’s policymakers as they scramble to manage sovereign exposure. The IIF said measures taken by the Chinese authorities to ease borrowing have led to a record jump in total aggregate financing to 6.6 trillion yuan ($1 trillion) in Q1 2016, a rise of over 40% year-on-year.

Asia is frequently touted as the global economy’s savior, but all of a sudden the region is facing intense headwinds as it grapples with China’s increasingly erratic economy and stalled global trade. Rajiv Biswas, Asia-Pacific chief economist at IHS Global Insight, told Global Finance that Asean (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) members have benefited from China’s economic ascendancy, owing to the rapid growth in exports to China, but this interrelatedness could become a double-edged sword if China experiences a hard landing. “Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines would be particularly vulnerable to the impact of a China hard landing due to their relatively open economies and significant manufacturing sectors.”

Asia’s big markets are simply failing to get traction. Employers are shedding jobs. Japan is sinking further, China dived again, and India has slipped. Admittedly, inventories are low, but restocking alone won’t stave off further economic malaise. Thus, China’s precarious debt position is not only a domestic issue—the increasing chances of a spillover, particularly in Asia, are significant. Between 2000 and 2015, China accounted for 22% of Asian exports, according to the International Monetary Fund. Recent PMI (Purchasing Managers Index) data summarily dispelled the idea that a spring bounce could be in the offing. It showed not only faltering export orders but further subdued domestic demand. New export orders contracted globally in April, led by China, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Singapore in Asia, according to HSBC and data from a regular survey conducted by Beijing-based Caixin Media Company.

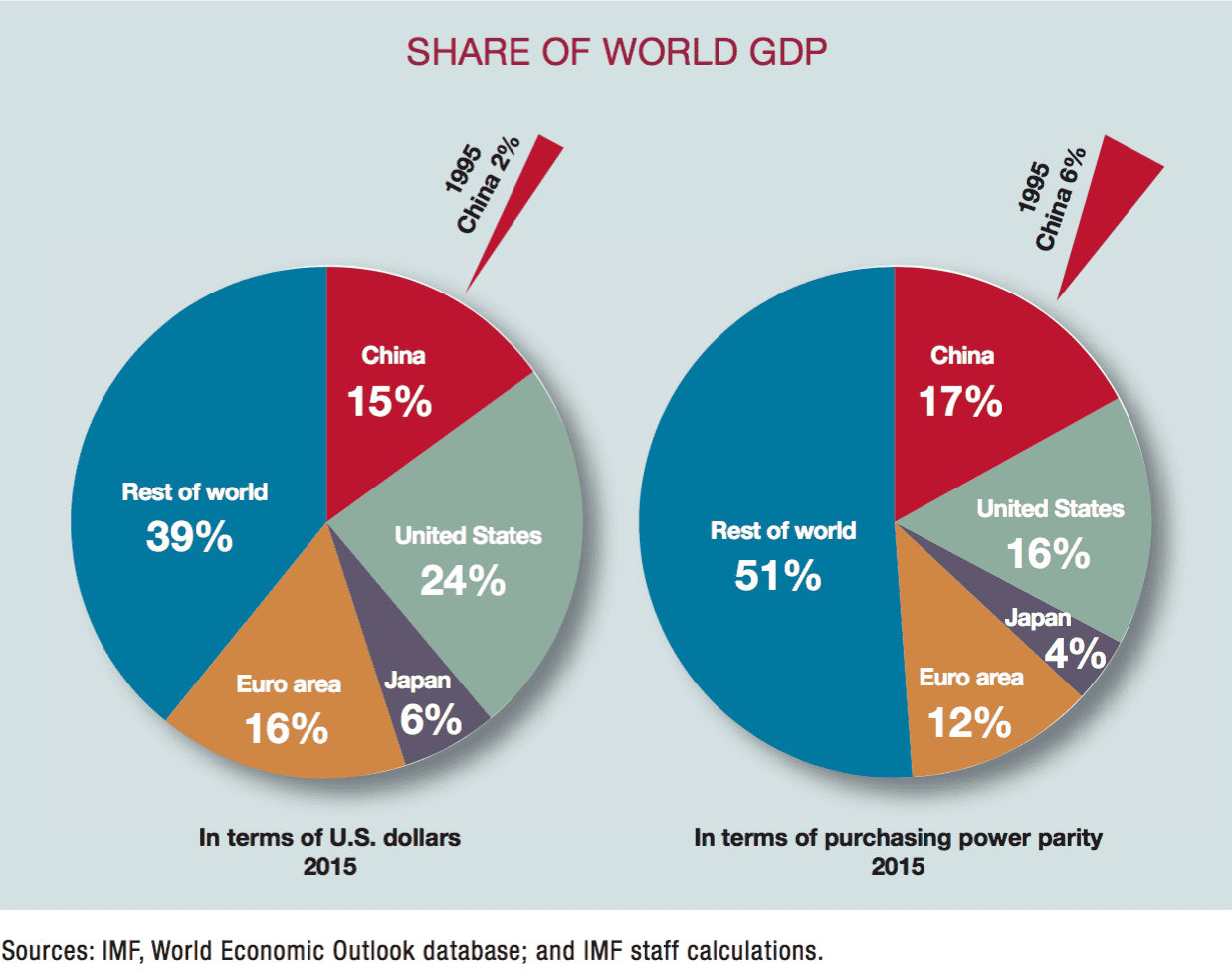

As China rebalances its economy to a model increasingly driven by consumption and services, risks to its Asian neighbors are not confined to trade but also to complex financial linkages. Recent IMF estimates suggest a one-percentage-point slowdown in Chinese growth translates into a 0.15–0.30 percentage point decline in growth for other Asian countries. China’s share of world GDP has also grown dramatically, which makes an orderly transition to a model with growth at a more sustainable pace vital (see chart). China bears responsibility for the travails of the rest of Asia, according to Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asia economics research at HSBC, and demand will remain low, “given that restructuring of (China’s) heavy industry has only just begun.”

According to the rating agency Moody’s, China’s state-owned enterprises (SOE’s) have liabilities equal to around 115% of GDP, and SOE debt that poses material risk is worth 20% to 25% of GDP. What is striking is that SOE liabilities in China are higher than those in any other rated sovereign. In Japan and Korea, where SOEs also have a sizable role in the economy, debt and liabilities amounted to 31% and 28.9%, respectively. Yet the extent of China’s SOE debt is open for debate—ANZ Research estimates the final tally as high as 145.2% of GDP at the end of 2015. Speculation over the extent of liability is one thing, but investors are clamoring for policy guidance from Beijing. Recent official comments seem to suggest an awareness, at least. In March, People’s Bank of China governor Zhou Xiaochuan warned that high levels of corporate debt could be a macroeconomic risk.

Still, in its latest World Economic Outlook, published in April, the International Monetary Fund pronounced Asian economies resilient. It forecasts growth in Asia-Pacific of 5.25% in 20162017. But there is a caveat: The IMF says policymakers should push ahead with structural reforms to raise productivity. It is too early to gauge the impact on cross-border trade of one major policy initiative—the Asean Economic Community of 10 countries that created a single market last year—but if the recent data is anything to go by, the question remains whether the much-ruminated soft landing is possible.

Getting Access To China’s $7 Trillion Bond Market

Undoubtedly the scale of China’s debt threatens the global economy, and the siege mentality adopted by Beijing has been criticized. But there are signs of change, as policymakers try to minimize the risk of contagion. Historically, Beijing has turned to debt-equity swaps as a way of deleveraging indebted firms, but that strategy looks increasingly unsustainable and is seen as a blunt instrument. “Simply ‘relabeling’ debt as equity (or effectively changing its tenor structure to perpetuity) cannot improve the quality of credit decision—policymakers should be cautious in proceeding with debt-equity swaps in a regime emphasizing market-based reform,” ANZ Research said in a note.

China has so far resisted using international debt capital markets, but local bond markets are showing signs of stress. Local corporate bond spreads have widened as investors’ concerns about defaults among SOEs and the recent wave of corporate ratings downgrades, which reached record levels in Q1, rise. According to the IIF, Q2 will surpass that record, with total downgrades already 30% above the total for all of Q1. Emre Tiftik, IIF deputy director, global capital markets, says market access for foreign investors has been expanded significantly this year, with banks and institutional investors now able to invest in the onshore interbank bond market directly without the constraint of quotas. “Many believe this will attract significant foreign investment over the next several years,” he says, “with some suggesting as much as $1 trillion to $2 trillion in inflows—a big impact on the onshore market, now worth well over $7 trillion.”

Beijing’s easing of access has been well received and prompted major providers of emerging markets indexes to consider including China’s domestic securities in their benchmark indexes. “As and when this happens, there would be scope for nonresident portfolio debt inflows to surge,” Tiftik says. “Between 2010 and 2015, annual nonresident portfolio debt investment accounted for just 0.2% of GDP in China, well below the figures in Korea (1.2% of GDP) and Japan (1.9% of GDP).” Despite grounds for optimism, there is residual uncertainty over taxation policy. The recent move toward a value-added tax from a business tax could theoretically penalize corporate bonds, as coupon payments would be subject to the VAT while those of sovereign bonds would not.

What About Reforms?

Adjusting policy without major reforms will only kick the debt can down the road, and when it comes to tackling SOEs, the reaction has been muted. Still, Beijing’s prevarication might be jolted. Official figures put the size of nonperforming loans at just 1.75% of total loans, which is widely thought to be an underestimate (some unofficial estimates put the figure at a whopping 25%). China faces a perfect storm of declining corporate profits, overlending in sectors with excess capacity and accommodative monetary policy. All of that worries investors as concerns over transparency impact sentiment. “Restrictions on capital mobility and concerns about currency and liquidity risks will continue to weigh on institutional demand for some time—hence in the near-to-medium term, investor appetite for Chinese debt is likely to be constrained,” says Tiftik.

China is now the world’s second-largest economy at market exchange rates, the IMF estimates, and the nation has been a key driver of global growth in recent years. No wonder the proficiency with which it continues to integrate into the global economy and transits restructuring is being closely watched by already-jittery financial markets. Judging by reaction to recent events, opinion is tilted toward the downside amid expectations of turbulence. As aviators know, a little turbulence can sharpen the mind but too much is destabilizing.