CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS: FOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Gordon Platt

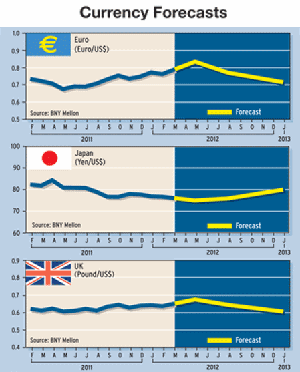

The euro’s surprising rise early this year, even as the European Central Bank flooded the market with liquidity, caught many market participants by surprise.

Net short positions in the euro hit a record high on the International Monetary Market of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange as 2011 drew to a close. The euro had dropped more than 11% against the dollar since late October.

“Sentiment was as extreme as imaginable toward the euro,” says Marc Chandler, global head of currencystrategy at Brown Brothers Harriman, based in New York. “The single currency’s five-week losing streak against the dollar was the longest in a year and a half and pushed the euro to 16-month lows against the dollar and 11-year lows against the yen.”

The extreme one-sided and one-directional nature ofthe market convinced Brown Brothers Harriman that instead of chasing the market, medium-term investors shouldlook for an upward correction in the euro “that will provide a better selling opportunity in anticipation of our midyear [2012 euro] forecast of $1.20,” according to Chandler.

“We suspected that the euro was vulnerable to an upside correction because many [in the market] had not yet appreciated the implications of the ECB’s three-year repo on December 21, which reduced the extreme tail risks in Europe,” Chandler says. The ECB announced on December 8 that it would conduct two longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) with a maturity of 36 months and the option of early repayment after one year.

Following the first LTRO in December, the Italian yield curve returned to its positive slope from inversion, and the Spanish yield curve became more positive. Dealers reported an easing in funding tensions, Chandler says.

BEST PRACTICE

In an era of floating exchange rates, which historically has produced a wide range of volatility, companies operating globally should execute a best-practice, global FX strategy, says Dan Perkins, Chicago-based principal in the finance and enterprise performance unit of Accenture, the global management consulting company.

Perkins recommends a two-tiered hedging approach, whereby corporate financial officials concentrate first on managing operational risks, and then do some hedgingof their currency exposure with forward contracts toreduce volatility.

“Companies should first identify some of the countries in which they operate where the currency is perceived to be weaker, and then protect against that volatility,” he says. “They can do that, for example, by moving some of their cash funds into a country where the currency is perceived to be stronger.”

Corporate CFOs and treasurers should also take a close look at their receivables in a weak-currency country and try to collect them as quickly as possible, reducing their assets exposed to the weaker currency, Perkins says.

“Corporations in general usually do a reasonably good job of managing their currency exposures,” he says. “They need to identify and measure this exposure and then hedgesome or all of it.”

FORWARDS FIRST

Most corporate financial officials are comfortable using forwardcontracts to reduce their currency volatility, particularlyif they are hedging for the first time, Perkins says. “They generallystart with three-month contracts and later extend themto one year,” he says.

Although options and more complicated derivatives couldbe used at a later stage, “you have to learn to walk first,” Perkinssays. By hedging little by little, companies can give themselvesmore flexibility, he adds.

Depending on the industry and the risk profile of thecompany, the amount of hedging a company does willvary, Perkins says. Benchmarks, he notes, can be usefulin keeping track of what similar companies are doing.However, each company needs to determine its own riskprofile and measure performance to the objectives selected,he adds.

Chandler of Brown Brothers Harriman says he is concernedthat a good part of the euro’s rally has passed andthat the news stream from Europe is likely to deteriorate.”The risk of a hard default in Greece appears to be rising,as one should expect [given that] the stakes are so high andthe brinkmanship tactics are used on both sides,” he says.”Portugal, which is now rated as below investment gradeby all three major rating firms, has come under increasedpressure,” he adds. The five-year credit default swaps forPortugal hit a record high [on January 24] as Portugal maynot only need a second aid package, but debt restructuringto boot, Chandler says.

FISCAL COMPACT

EU leaders met in Brussels on January 30, in the first EUheads of state summit of 2012, to discuss the new fiscal compactfor tighter budgetary control that would move the eurozonecloser to a fiscal union. “Markets hope that the agreementwill give the ECB more room to maneuver, given thatstricter rules and further budgetary oversight is likely to limitmoral hazard concerns,” Chandler says. “Yet, there is no signof an agreement in Greece, which has rejected calls for a budgetarycommissioner to oversee the Greek budget as part of anew bailout package.”

Michael J. Woolfolk, managing director of BNY MellonGlobal Markets, based in New York, says the euro’s latest rallyshould not be mistaken for a vote of confidence in Europe.”Rather, it was a reversal of overextended long dollar positionsbuilt up ahead of the latest round of European debtnegotiations,” he says.

“With a technical default of Greek sovereign debt a foregoneconclusion ahead of the March 20th refunding deadline,the question remains whether or not Greece is allowed to stayin the eurozone,” Woolfolk says, adding that the risk ahead of this decision is clearly negative for the euro. “However, the risk after the decision will depend less on what decision is madeand more upon how that decision is implemented,” he says. “Ring-fencing Greece with a collective eurobond backed by a eurozone finance ministry is an intriguing prospect.”

GERMAN BLUNDER

Although German chancellor Angela Merkel won support for the fiscal pact at the EU summit on January 30, including binding limits on budget deficits and semiautomatic sanctions on countries that breach deficit and debt limits, the meeting did not go exactly as planned. In addition to the usual message of austerity, the summit was designed to include a commitment to jobs and growth.

“This is not a choice between fiscal consolidation and growth. We need both,” Jos Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission, said in a statement. The pro-growth message was overshadowed, however, by worries that Germany was seeking to put Greece’s budget under EU control.

The controversy was inflamed by public reports of an internal German finance ministry paper suggesting that Germany wanted to dispatch an EU budget commissioner to Athens to monitor Greece’s fiscal policy. An austerity minister just for Greece alone is not acceptable, said Luxembourg prime minister Jean-Claude Juncker. One EU leader after another sided with Greece on the issue.

Nonetheless, Merkel called the summit a “very successful result,” as 25 of the 27 heads of government signed up to the pact for stricter fiscal discipline. Britain and the Czech Republic were the only EU members that refused to join the fiscal pact.

YEN OUTLOOK

Masafumi Yamamoto, chief foreign exchange strategist at Barclays Capital in Tokyo, says the dollar-yen exchange rate is at a crossroads and that the Japanese currency will likely weaken over the next 12 months. The dollar-yen pair has exhibited relatively large swings since mid-January,and Japan’s trade balance seems likely to remain in deficit for the remainder of 2012, due to higher fuel imports,he says. The current account should remain in surplus, however, given the strength of Japan’s income surplus, Yamamoto says.

The dollar-yen exchange rate has remained within a narrow trading range of 76 yen to the dollar to 79 yen to the dollar since the massive intervention by the Bank of Japan, at the direction of the ministry of finance, at the end of October 2011, Yamamoto says. “If the US Federal Reserve’s enhanced policy guidance and extended policy time frame [vowing to keep rates low until late 2014] succeeds in anchoring interest rate expectations, then it is possible that the monetary policy outlook should remain impervious to either positive or negative surprises from incoming economic statistics,” he says. This could put relatively greater attention on Japanese factors, he adds.

Japan’s current-account surplus shrank at a record rate in 2011. Fears of a sustained current-account deficit could be triggered by an unexpectedly strong rise in imports. “Fuel imports in particular could easily rise due to growing fuel demand since the March 2011 earthquake, and oil prices could be pushed up by Iran-related geopolitical tensions,” Yamamoto says. Barclays Capital made mild upward revisions in its dollar-yen forecast on February 8, projecting that the yen would weaken from about 77 to the dollar to 83 in one year.

As a current-account surplus is one of the key underlying assumptions as to the stability of the Japanese government bonds market and strength in the yen, the prospects of a slide into deficit could be a negative for the yen over the long term, Yamamoto says.