As fears grow that Chinas economy may be dangerously overheated, analysts are increasingly drawing parallels with Japans experience over the past three decades.

China has been hogging the headlines in recent monthsand justifiably so. Around the world, analysts, investors and businesses are hungry for news of an economic growth engine that will help to drive the global economy out of its slump, and China seems to be gearing up to do just that. Even as the breathless reports pile up of Chinas economic potential, though, predictions of its demise are becoming increasingly common.

Central to the gloomy predictions of the doomsayers is the fact that the Chinese banking system suffers from an overload of ill-considered lending and a mountain of real or potential non-performing loans. The country as a whole has more than its fair share of crony capitalism, and the phenomenal economic growth of recent years has been fueled as much as anything by sheer enthusiasm. In fact, its a lot like Japan in the 1970s.

The possibility that China is the new Japan could be both a blessing and a curse. While Japan remains a heavyweight, boasting the worlds secondlargest economy, it has only recently pulled itself out of yet another recession. No one is sure that it wont slip back into recession soon.

China on the other hand has witnessed stellar growth of recent yearsbut it may well be a bubble waiting to burst. Japan has every reason to worry about that because a faltering Chinese economy would almost certainly take Japans fledgling recovery down with it.

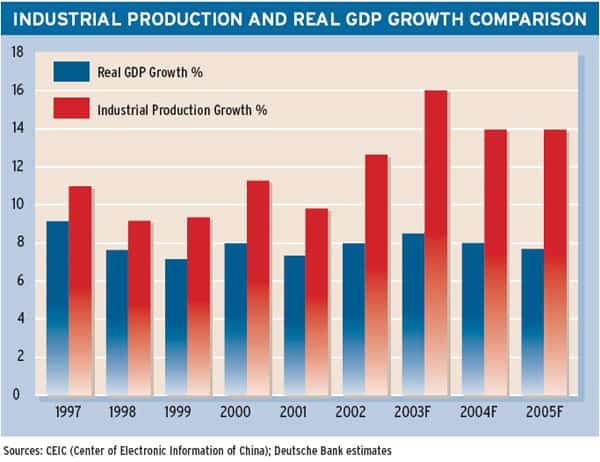

The two economies recent experiences couldnt be more different. Over the past decade, as Japan struggled with a stagnant economythe fallout from unchecked growth in the 1980sChina was reporting annual average GDP growth of over 9%.Then, in 2003, Japan joined Chinas growth spree, lifting itself out of its moribund state to attain an annualized real GDP growth of 7% in the final quarter of 2003.

Its no coincidence that Japans fortunes are reviving. Jesper Koll, chief economist at Merrill Lynch in Tokyo, explains: If you do the arithmetic, you see that 30% of Japans growth was from exports over the last one-and-a-half years.And 85% of those exports were to the Peoples Republic of China. Even a minor slowdown in growth could have a significant impact on Japan, while an implosion of Chinas economy would have severe ramifications for Japanand, indeed, the rest of the world.

There are few reasons to conclude that Chinas economy will suffer a meltdown, though. While it shares a surprising number of Japans underlying problems, it is unlikely to plunge into a recession as Japan did at the end of the 1980s. This is because the current overheating is basically cyclical, rather than structural, in nature. Despite several fundamental weaknesses, some reminiscent of Japan, China remains a strong growth story in the medium- to long-termassuming it continues its reform program. As a result, while most analysts agree that the countrys economy is set to slow down over the next two years, they view it as hitting a speed bump rather than undergoing a full-blown crash.

Growing Pains

There is no doubt that China is hurtling toward Western-style modernity with unprecedented speed. Patrick Powers, director of China operations at the US-China Business Council in Beijing, describes a burgeoning middle class, which began to do some serious spending on itself in 2003. Last year saw the emergence of three distinct cultures in the country, he says: the automobile culture, the property/home-improvement culture and, of course, the finance culture, because people have to find a way to pay for the other two.

Deutsche Banks head of Greater China equities, Jing Ulrich, found that automobile spending surged last year, with passenger-car sales almost quadruple the growth rate recorded in 2001. According to HSBC figures, the homeownership rate also jumped, surpassing 70% in most cities in 2003. Consumers, meanwhile, accounted for a high 20% of new loans last year, notes Ulrich.

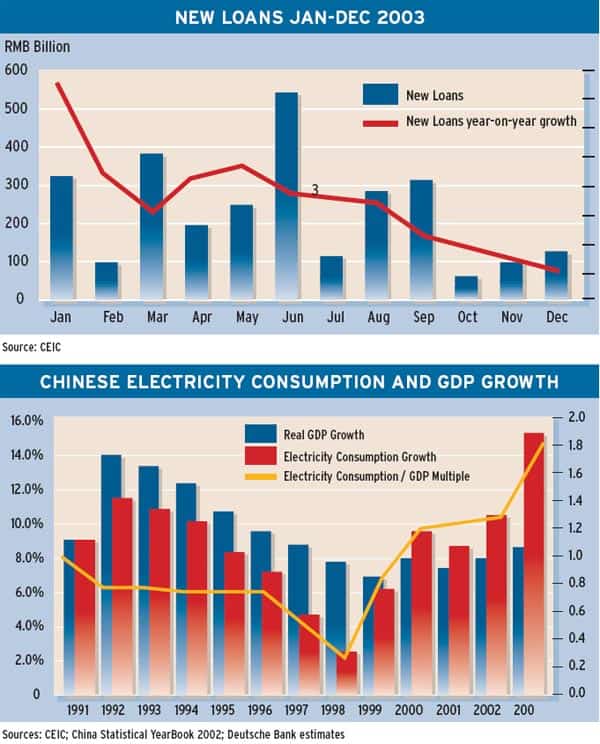

Chinas growth story is not simply a result of a consumer spending spree, however. Total bank credit increased 21% in 2003, and, as analysts pondered whether the new year would bring a slowdown of sorts, fixed-asset investment surged 50% year-on-year in January-February, according to HSBC.

| |

|

Much of this stems from industrial ization. Qu Hongbin, senior China economist at HSBC in Hong Kong, points to Chinas rapid industrialization and urbanization, and claims that the hasty development being witnessed in China largely derives from local governments eager to win brownie points with the central government. The emphasis has been on attaining lofty GDP growth figures with little thought given to sustainable progress. A recent Chinese study, notes Hongbin, shows local governments in the process of creating 3,837 industrial parks and development zones across Chinaequal to 1.5 times the current urban area, or 62 times the size of Singapore.

Eddie Wong, chief Asian strategist at ABN AMRO in Hong Kong, emphasizes the continued excesses of Chinas state-owned enterprises, which are also forging ahead with little appreciation of the bigger picture. Despite decades of ill-considered investments, many still rush to buy into the latest phenomenon with little concern for what their counterparts are doing and how it will affect their business.

This unchecked development is generating signs of overheating in a number of key sectors, say economists, including steel, aluminum, cement and the property sector.As the rampant development leads to overcapacity, many are concerned that Chinas banks are lining up another round of non-performing loans for Chinasomething the country can ill afford.

Echoes of Japan

Chinas rapid growth story harks back to Japans swift rise to economic power in the latter half of last century. China has to be hoping its boom will not go the way of Japans, though, which imploded under the weight of collapsing real estate and stock prices and a raft of non-performing loans. Some are already predicting that Chinas economy will also buckle under the pressure of overwhelming growth and sink into a prolonged period of stagnation.

Although the current overheating can be explained away as cyclical in China, one cannot ignore the structural issuesfundamental problems that China shares with Japan and that it will need to address if it is to enjoy sustained growth. Both China and Japan suffer from weak financial systems, which threaten to undermine the very foundation of their economies. Both maintain an overload of non-performing and sub-performing loans left over from a myriad of failed ventures in the 1980s.

Historically, the countries banks have been highly protected by their respective governments. There has been little incentive to pursue debtors when fixedterm loansand even the interestare often rolled over as a matter of course. In turn, companies have also shown little concern for the health of their balance sheets. While corporate Japan is beginning to move beyond this, China has a long way to go. The problem is that the Chinese companies have little sense of the cost of money, says Wong.

Japan appears to have halted its prolonged rise in NPLs, and, according to Teikoku Databank, bankruptcies dropped by 14.6% last year, the first decline in four years. Japans major banks also took unprecedented steps in 2003 to clean up their balance sheets, exploring the use of more adventurous financial products such as synthetic securitization to offload trillions of yen in debt. However the Japanese government along with most banksstill takes the position that many companies are too large to fail, and it forgives bad debts accordingly.

Chinas financial institutions are less sophisticated than Japans; one analyst described them as primitive. Says Wong: Risk control and credit assessment are not well developed yet. The current incentive systems also encourage over-lending. China set up four asset management companies in 1999 in order to offload 1.4 trillion yuan in non-performing loans from the countrys state commercial banks, but there is every chance that the current credit splurge will result in a new round of bad debts.

Making the Same Mistakes

According to Robert Feldman, chief economist at Morgan Stanley Japan, the most striking similarity between China and Japans problems is their misallocation of capital, reflected in their deteriorating return on assets. While China has seen its return on assets decline from 20% in the early 1980s to 5% in recent years, according to Nicholas Lardy, a scholar at the Brookings Institution, Japan has hovered around 2% over the past decade. Thats down from 4% prior to 1990, says Feldman. Feldman, who records Lardys figures in a report produced in July 2002, notes that while Chinas figures may not be strictly comparable to Western-style accounting, the sharp decline is nevertheless incontrovertible.

Of course, the two countries do differ in obvious ways, but not always to the benefit of Chinas economic outlook. China is at an entirely different stage of development from Japan, after all. And despite a strict authoritarian regime, it is also hampered by its cumbersome geographical size.That makes it more difficult for the government to control the countrys growth. Glen Fukushima, chief executive of Cadence Design Systems Japan and former president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan, says: China’s growth is less centrally managed and controlled than Japan’s was in the 1960s and 1970s, so the risks of disruptions are greater. He points to the disparity in income in China and argues that it is much greater than it was in Japans high-growth phase, as is the disparity in wealth across geographical regions.

But China has already shown itself willing to endure significant reform and a strong will to restructure going forward. It bodes well for the long-term health of its economy. Over the past 20 years the government has made concerted efforts to address a range of difficulties it facesin stark contrast to Japan, which has spent the past decade avoiding heavy-handed restructuring.

While it is often difficult to notice change in a giant monolith like China, the progress has been real. As Stephen Roach, economist at Morgan Stanley, notes in his December report, Reforms in China are proceeding at a pace that is almost impossible to fathom from outside. Although the countrys state-owned enterprises remain huge and unwieldy, the government has been reducing headcounts significantly around 7 million to 9 million jobs annually, says Roach. And even as the country is set to lose millions of more jobs each year, through restructuring and as a result of joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, the government is working to create new positions and retrain its people. For 2004 it aims to create 9 million jobs, maintaining unemployment at 4.7%.

It is an issue that Japan has sidestepped wherever possibleand for which it has been often criticized. Despite the fact that the country has an enviable social security system, losing ones job remains highly taboo in Japanan issue that ha stood in the way of much-needed reforms and prolonged its economic woes as a consequence.

Another area where China distinguishes itself is in its fostering of foreign direct investment (FDI). Unlike Japan, China has embraced foreign capital, much to its benefit. According to the China Chamber of International Commerce, 41,081 FDI enterprises were established in China in 2003, up by 20% over the preceding year. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development put Chinas FDI for 2003 at $57 billion, another record high for the country and more than five times that of any other developing economy.

Japans FDI on the other hand was down, at $7.5 billion, lagging far behind most of the developed countries. Says Fukushima, One of the lessons that Japan can learn from China is the benefits of inward foreign direct investment to the growth and vitality of the host nation. He points to the fact that China has used FDI to considerable effect as a way to gain such benefits as tax revenues, employment, technology, innovation and new management methods.

China Applies the Brakes

As is all too often the case with respect to China, the West just doesnt get it, notes Morgan Stanleys Roach. Missing from the worlds assessment of China, in my view, is the perspective from the insidethe overarching imperative of China to stay the course of reforms without disturbing social stability.Roach believes that the country cant afford

a hard landingand wont allow it.

Certainly the government has its eye firmly on the macro economy just nowand on longer-term structural reforms. According to Qu at HSBC, it is very aware of the threats facing it and has been refreshingly open about them: China does have a serious overheating problem.We can use a number of ways to try to measure the problem, but its not that important.What is important is that policy makers recognize the risk and try to do something about it.They are.

One approach has been to rein in the excesses of local governments. Says Qu: The central government has to do something to impose discipline on the

local governments. If the central government can regulate this, it can engineer a slowdown. He believes that it has already taken promising steps. In March the government clearly articulated the need for local authorities to focus on the quality of growth: social development as well as economic development.

Chinas government has also taken preliminary steps to tighten credit and monetary control.However, the governments power over the banks is no longer absolute. Says US-China Business Councils Powers: The government is very well aware of the situation, but it is not a monolith, so its difficult to control bank lending down to the retail levelalthough they are trying to rein in the more egregious lending practices.

Most agree that any landing will be a soft one, buffered by the countrys vast resources. Consumer spending is likely to cushion much of the slowdown as rapid urbanization continues well into the next decade. Says Powers: The key to Chinas success is domestic demand and further growth of consumer spending in the long term.That doesnt mean there wont be speed bumps along the way and there will be some economic pain, but they will get through it as they have in the past.

Japans Window

So where does that leave Japan? The pessimistic view is that even a slight slowdown in Chinas economy could trigger another recession.Koll at Merrill Lynch, however, believes Japan has a unique window of opportunity over the next six to nine months to convert export growth into consumer growth, and he holds out hope that the country will take advantage of it.

Japan has shown promising signs over the past 12 months. Its companies and financial institutions are becoming increasingly competitive as they pursue long-needed reforms.The governments economic management has also been more decisive.

But skepticism is warranted, and whether Japan goes on to make the very most of the opportunities presented by an economically powerful China remains uncertain. Like China itself, Japan needs to rectify many of its problems if it is to make the most of a post-WTO China.

Of course, there is one final problem: The two countries relationship is not entirely cordial, and hostilities from the previous century have not been easily forgotten. Concludes Fukushima, Of course there are the simmering political issues between Japan and China that inhibit the full realization of mutual economic benefit. Perhaps it will be that mutual benefit that will finally allow the two nations to bury the hatchet.