Despite recent setbacks, France is still working hard to push through social and economic reforms.

With the French saying non to the EU constitution earlier this year and the outcome of the German election sending mixed messages about the publics appetite for radical market reforms, Anglo-Saxon newspapers have taken to calling France and Germany the new sick men of Europe. Britains The Guardian newspaper characterized the prevailing response to structural reforms in the eurozones major economies as resistance to any radical changes to the old social market economy.

Economists and the OECD have been vociferous about the need for structural reforms within France, Germany and Italy to help lift the major eurozone economies out of their general economic malaise. Michala Marcussen, head of strategy and economic research at Socit Gnrale Asset Management, believes that Italy is the weakest link in the eurozone, with France and Germany already taking steps toward economic recovery. Germany has done a lot of corporate restructuring and has led in terms of labor market reforms. France has also done a number of things in terms of mass reforms. Most of the focus has been on the downsides of the 35-hour working week, but it should be kept in mind that more flexibility has been introduced to the labor market. The most recent measures from the government are also heading in the right direction, she says.

Marcussen is referring to the announcements by French prime minister and presidential hopeful Dominique de Ville-pin, who outlined in August his vision for reducing unemployment by introducing more flexibility into hiring and firing workers. In September he announced the second stage of his economic recovery plan, the central tenet of which was instituting tax cuts worth -3.5 billion, as well as financial incentives to encourage the long-term unemployed back to work and measures to reduce abuse of the welfare system. His presidential rival, former finance minister Nicolas Sarkozy, also placed tax reform at the heart of his economic recovery plan, while inflexible labor laws were the cause clbre of Angela Merkel, the Christian Democrat leader who failed to win an outright majority in the recent German elections.

While Sarkozy and Merkel wore their reformist agendas on their sleeves, de Villepin appears to be more coy about his. Many thought not much would happen [under de Villepin] because of the opposition to reform that was made evident by the referendum, remarks Philippe dArvisenet, global chief economist, BNP Paribas. DArvisenet says that under the current tax regime, financial wealth was taxed several times, which was an incentive for higher-income earners to take their money elsewhere, thereby eroding the tax base. French employers have also complained that complicated legal proceedings meant that most employees waited for huge payouts before leaving a job, which discouraged companies from hiring even in prosperous times. One of de Villepins more welcome labor market reforms was to allow SMEs with fewer than 20 employees more flexibility in terms of hiring and firing people within the first six months. More flexibility in the labor market for smaller firms should encourage them to create jobs, says Professor Philippe Martin, a research fellow with the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

Martin says unemployment in France had already declined in the past five months from a high of 10.2% in May to 9.9% in August, but he explains that this fall is due mostly to tougher policies on unemployment benefits and to the creation of jobs subsidized by the public sector. The increased flexibility for smaller firms will produce jobs, but only later on, he adds. DArvisenet says by making it easier to hire and fire for a limited proportion of the labor force, some employees could remain unprotected and employers may rely on temporary labor, while others remain extremely protected, which could intensify the segmentation of the labor market.

In terms of reducing the number of people claiming unemployment benefits, it may be a good idea, but dArvisenet says it could be difficult to implement, as unemployment officers may not be as strict as they should be. Marcussen concurs, adding that while tightening up the rules for claiming unemployment benefits looks good on paper, its success is uncertain.

|

|||

|

Martin believes there is a tendency to underestimate the pace of economic reform in France. The politicians in France say they are not going to support the Anglo-Saxon model and that they are against globalization, but in fact the labor market has been reformed quite a lot already, he says, pointing to the relatively healthy balance sheets of the French corporate sector. Since the beginning of the year, Martin notes that the French stock market gained 15%, the strongest performance in the G-7 group. So it is difficult to explain that nothing has happened, he continues, but you also need economic growth, which we dont have yet.

DArvisenet says that, given the lack of consumer confidence, which is tied to the performance of the labor market, it is difficult to see the French economy rebounding any time soon. He projects that the French economy will grow by 1.5% this year, significantly less than the governments forecasts of 2% to 2.5%. Some recovery in consumer demand emerged in August, with cost cutting by retailers resulting in consumer spending increasing 5.7% from a year earlier. According to French statistics office INSEE, spending on manufactured goods increased 1.9% from July to August. Marcussen says France has enjoyed higher income growth than Germany and that there had been growth in consumption, particularly in the housing market. According to Bank of France figures, French household borrowing in the 12 months to June increased by 9.2% to _158.4 billion.

Although business confidence in the eurozone has risen on the back of a weaker euro, the INSEE business confidence index of manufacturers dipped to 100 in September, down from 101 in July. However, according to the Center for Economics and Business Research, a sub-index on French production increased to a five-month high of -14 compared with 24 in July. There are some companies out there that are hesitant about taking the next step to start investing, even now that they have strong corporate balance sheets, says Marcussen. European companies are waking up to the new reality of the global economy, and large companies in France and Germany understand that.

Historically, Germany has fared better than France in terms of annual growth in merchandise export volumes. However, in the first quarter of this year annual export volumes increased 6.5% over the previous year in France, compared to an increase of only 0.9% in Germany. Some observers believe France has been more successful than Germany in making the transition to a service sector economy. However, despite the gains Germany has made in wage restraint and productivity, the price competitiveness of German goods is not much higher than French companies, says dArvisenet. But Germany is producing the kinds of products that are demanded, and they are present in dynamic regions of the world such as Asia. That is not necessarily the case with French manufacturers.

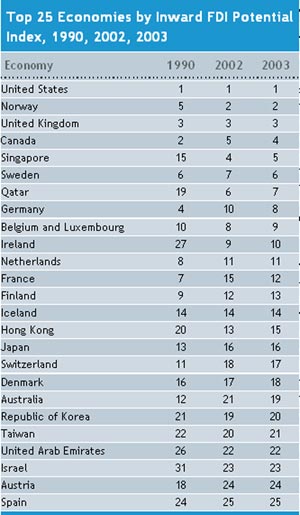

In 1990 the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) ranked France seventh in its Top 25 Economies by Inward FDI Potential Index. But with other economies competing for foreign investors dollars, Frances ranking slipped to 12th spot in 2003, behind Germany in eighth position but ahead of Finland, Denmark and Spain (see table). France has been encouraging FDI and has a well-educated workforce which is attractive to foreign investors, says Marcussen, but there is growing interest in Germany at the moment.

Yet when ranked out of 140 countries for inward FDI performance in 2004, France in 80th position performed better than Germany (118), according to UNCTADs 2005 World Investment Report. UNCTAD pointed to increasing competition for FDI as well as the impact of factors such as corporate tax. According to UNCTAD, EU investors were more likely to increase FDI by approximately 4% in those countries that reduced corporate income tax rates. France decreased its corporate tax rate from 34.33% in 2004 to 33.83% in 2005, but it was still significantly higher than countries such as Denmark, where corporate tax is 28%, and Finland, where it is 26%.

Given its location in the middle of the EU, Martin believes that France is in a good position geographically to attract foreign investment. France has good market access in Europe and good public infrastructure, he says. But labor costs remain high compared to other countries, and the unions still have a stranglehold on certain industries. De Villepin has also sent mixed messages to foreign investors. In August, when he announced his emergency plans for creating more jobs, he said France would adopt a protectionist stance toward strategic economic sectors to prevent takeovers by foreign companies in what he termed economic patriotism.

In July de Villepins economic patriotism was put to the test when rumors circulated that Frances Danone was about to be bought by US drinks giant Pepsi. Not surprisingly, Frances response to the rumored bid was not too dissimilar to the outrage the country expressed when Disney came to Paris. Responding to Pepsis rumored bid, finance minister Thierry Breton was quoted as saying: France is not the wild west. We have a strict framework of laws, and we will ensure that the law is applied so that the interest of employees will be protected.

Yet dArvisenet questions whether a company such as Danone, which produces yogurt, can be viewed as a strategic industry. That is political posturing, he says. Since then, a list of strategic industries has been published, and it does not include food processing.

Anita Hawser