COVER STORY: KENYA – REBIRTH OF A NATION

By Dan Keeler

|

|

With a new constitution, bold economic targets and an ambitious social development strategy, Kenya is determined to become the new star of Africa. All the signs so far suggest it may yet achieve its goal. |

On a recent fact-finding mission to Kuala Lumpur, members of a Kenyan government delegation were surprised when their Malaysian hosts, after greeting them warmly, thanked them for their help in making Malaysia’s capital city such a success. “They explained that, several decades earlier, Malaysia sent a similar delegation to Nairobi to find out how to create a modern capital city,” says one of the members of Kenyan team. “They told us Kenya’s capital was the model for Kuala Lumpur,” he adds.

Decades later, and with the tables unequivocally turned, Kenya is taking a very careful look at how Malaysia and the other Asian tigers built their tremendously successful economies from the ground up. With the lessons it is learning, Kenya aims not just to replicate their success but to exceed it.

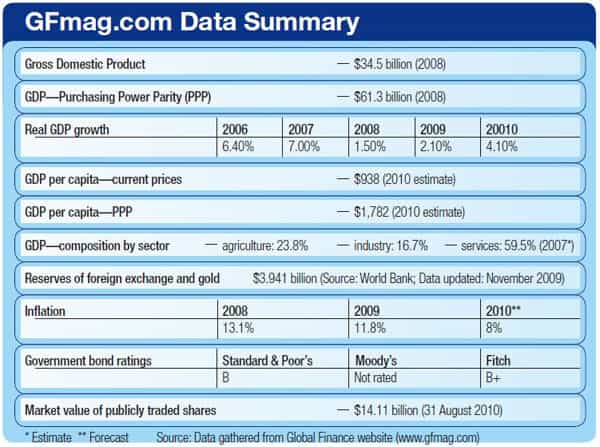

To anyone who hasn’t visited Kenya recently, the country’s claims and ambitions may sound like wild hubris. Even the most optimistic reputable estimate of GDP per head puts the figure at only $1,000 a year. Unemployment is rife, particularly in rural areas. The country’s economy has a track record that is patchy, to say the least, and it’s in a corner of East Africa that’s more often associated with famine, war and piracy than with rapid and stable economic growth and social progress. But spend a little time in the bustling, vibrant capital or in the lush landscape of the fabled Rift Valley and suddenly the Kenyan leaders’ vision of their country as one of the world’s rising economic stars—Africa’s lion to Asia’s tigers—doesn’t seem so far-fetched after all.

Conceived more than a decade ago, that vision is now becoming a reality. In late August, Kenya’s president Mwai Kibaki signed the country’s new constitution into law. As he did so, creating what many are calling the “second republic,” Kibaki said: “This new constitution is an embodiment of our best hopes, aspirations, ideals and values for a peaceful and more prosperous nation.” His words capture the spirit of the new Kenya, a country that is driving hard to become the de facto gateway to East Africa, the principal trade hub between Africa and Asia, and the region’s economic and political powerhouse.

The country has an ambitious infrastructure construction program, a determination to upgrade its power generation grid and transform the country into a green energy leader, and a new constitutional structure that will help Kenya establish a fairer and more transparent political system and a more balanced economy. Through its “Vision 2030” program, Kenya has committed to promoting economic growth, creating “a middle-income country providing a high quality of life to all its citizens.”

As well as promoting domestic growth, Kenya is looking for international partners to help it achieve its ambitious plans to grow its financial services, manufacturing and outsourcing industries. In its effort to modernize and grow its economy Kenya is also blazing a trail that other similar emerging markets will want to follow.

Mugo Kibati, director general of Vision 2030, says the organization’s mission boils down to achieving one simple goal: “We want every kid growing up to be assured of a job,” he says. “We have an overarching vision to transform Kenya into a globally competitive, prosperous nation with a high quality of life for all by the year 2030.” If the goal is clear cut, the process of achieving it is anything but simple and will involve a transformation not just of the constitutional structure of the country but of its culture.

Three-Pronged Approach

Kenya has broken its reform program down into three distinct but interdependent pillars: political, social and economic. With the ratification of the new constitution, which should lead to the development of a more stable, transparent political system, the construction of the first pillar is well under way. The aim of the social pillar is to create a “just, cohesive society” with universal access to education, healthcare, housing, food, water and sanitation. In the education field alone, the goals are ambitious: Kenya hopes that by 2012 it will be able to boast an 80% adult literacy rate and a 95% school enrollment rate.

The economic pillar is focused on significantly boosting growth. “We aim to achieve a consistent 10% annual growth rate sooner rather than later, maintaining that until at least 2030,” says Kibati. “We want to move our economy up the value chain.” To do so, Kenya is leaning heavily on its corporations—large and small—and its business leaders, many of whom have been brought in to help guide and implement Vision 2030.

“We cannot overstate how critical private sector participation is in Vision 2030,” comments Kibati. “Roughly 70% of the projects in Vision 2030 are meant to be implemented via private sector participation.” Many of those projects will focus on developing and promoting six key areas of the economy: tourism, agriculture, wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing for the regional market, business process offshoring and financial services.

To facilitate the growth of those sectors, the country has embarked on a substantial infrastructure investment program. The plans are nothing if not ambitious, involving port construction, airport expansion, a massive improvement in and extension of the country’s road network, the creation or upgrading of road and rail links from Kenya’s ports to central Africa and to countries north of Kenya, a threefold increase in electric power generation capacity and a new oil pipeline to the coast.

For the companies already operating in Kenya, one of the most welcome developments will be the expansion of the electricity generation capacity. For several years there have been concerns that the country’s generating capacity is constraining its economic growth. With a heavy reliance on hydropower, it is also vulnerable to fluctuations in rainfall—a risk exemplified by a prolonged drought in 2009, which led to severe electricity shortages. As well as building a more diverse and reliable power generation system, Kenya is also determined to become a world leader in sustainable power generation. Sam Mwale, Kenyan president Mwai Kibaki’s principal administrative secretary, explains: “We have decided to add 2,000 MW of power, of which 70% will be green energy. We want to choose a different path.” The new generation capacity will include geothermal, solar and wind-power plants.

Gateway to the East

While the electricity generation expansion will be capitalizing on Kenya’s geological advantages, much of its other infrastructure spending is focused on taking advantage of the country’s geography. “Kenya’s unique strengths include its location on the central-eastern coast of Africa, which offers access from the Indian Ocean to the entire hinterland of east and central Africa,” says Kibati. With plans to expand the country’s existing port in Mombasa, to build a new port that will handle the latest super post-Panamex container ships, and to build road and rail corridors to link the ports with the rest of Africa, Kenya is setting its sights firmly on becoming the primary gateway for trade between East Africa and Asia.

Such projects don’t come cheap, however, and Kenya is hoping to fund much of the work through a combination of public-private partnerships (PPPs), development grants or loans and government funding. The PPPs will provide opportunities for foreign investors to get involved in the infrastructure build-out. “Currently, we are still in the feasibility study stage for most of the biggest projects, but we already have international partners lining up to participate in some of the projects, such as the new port,” says Kibati.

In an effort to ensure the country’s infrastructure and business development plans don’t get snarled up in political infighting—and that the process of reform would be as transparent as possible—the politicians behind Vision 2030 established an unusually open and inclusive planning structure. A key part of that structure is a steering committee made up of business leaders and senior civil servants. “We ensured there were no politicians so that we don’t politicize the process,” says James N. Mwangi, group CEO of Equity Bank—one of East Africa’s largest banks—and a member of the team responsible for implementing Vision 2030.

Business leaders’ access to government extends to the very top level. “We have a dialogue twice a year with the president,” says Patrick Obath, chairman of the Kenya Private Sector Alliance (Kepsa). “If there are issues that require political goodwill, we ask the president to facilitate it. It is his role to bring everybody politically on board to implement some of the things that may [otherwise] get stuck.”

Nick Mbuvi, the commercial banking director at Barclays Kenya, believes that the way the strategy is being implemented should ensure both transparency and accountability: “At the end of the day, the people running this project, because they are not politicians, can be fired. That in itself makes them accountable.” It also helps ensure the reforms are business-friendly.

Obath says the business leaders’ involvement has already had a profound impact on the policies and strategies underlying Vision 2030: “The regular contact we have had with government has meant that every single activity that is done there does take business into consideration,” he says. “As a result, [the legislation] is relevant to and, most of the time, meets the requirements of the business community in this country.”

Building Trust

Few would dispute that Kenya’s effort to transform itself is laudable, but the success of the project is heavily dependent on its building and maintaining the trust of both Kenya’s population and the international investors the government is hoping will be drawn to the country. The president’s insistence on transparency and clear personal accountability for all those involved is a clear attempt to ensure the public trusts the process. Mwangi says the public has been instrumental in establishing the country’s long-term goals. “The president insisted on a thorough public consultation process to ensure the Kenyan people were involved in the future plans,” he says. “The consultative project showed us what would be the most important, visible and valuable projects to the Kenyan people. It also brought unity of purpose to the Kenyan people. It removed this process from government and gave it to the Kenyan people.”

The Kenya Investment Authority, which is responsible for encouraging foreigners to set up shop in Kenya, is hoping that same transparency will also reassure investors. Susan Kikwai, managing director of KIA, says the rules governing foreign investment should help instill confidence in companies looking at expanding into Kenya. “We have no exchange controls,” she says. “Once international investors come to Kenya, they can have a 100%-owned entity here and can repatriate all their profits, once they’ve paid the appropriate taxes.” She also points out that Kenya is a member of various international investment guarantee and dispute resolution bodies that help ensure transparent and fair treatment of investors.

As well as establishing a business-friendly environment, the KIA offers a one-stop advisory and investment facilitation service “so businesses looking to set up in Kenya have one point of contact when they start to set up here,” she adds. “We can put them in touch with all the people they need to work with in order to establish their business. We will also help businesses get all the permits they need—licenses, work permits and so on.” One of the benefits of this facilitative approach is that it makes the process of setting up in Kenya much more transparent and much simpler. “We are positioned to be the country of choice for investors,” Kikwai asserts.

Kepsa is also working to persuade potential investors that Kenya is a viable and stable place to do business. “We welcome investment from anywhere in the world to help transform this country,” says Obath. “Kepsa will ensure that the environment is created and maintained that will enable that.”

Mwale notes that Kenya is setting up a range of special economic zones, specifically aimed at attracting manufacturing and services companies. “A lot of interest will come from Asia—particularly South Korea, China and India,” he says. “There will be a lot of incentives, such as tax holidays and so on.”

According to Mbuvi, Kenya’s efforts to attract investment are already paying off. “We are getting an excellent response from investors looking at getting involved here, particularly in the infrastructure projects and in the energy sector. A lot of foreign investors have already discounted the political risk here,” he says.

Jostling for Regional Supremacy

A flurry of recent deals between the region’s key economies may entice yet more investors to dip a toe in the Kenyan market. As the ink was still drying on Kenya’s new constitution, the five countries that make up the East African Community—Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda—were hammering out the details of a pact that will lead swiftly to the creation of a regional common market. The market won’t open immediately, but the EAC members have agreed to bring down all trade barriers within five years; to ensure free flow of goods, people and capital; and to establish a customs union. The organization may also become significantly larger in the medium term. “We have a couple of countries knocking at the door to join the EAC,” says Kibati. “Southern Sudan and Democratic Republic of Congo are both potential candidates.”

There are also plans to create a much bigger East African trading bloc that would link EAC with two other regional groups—the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (Comesa). Mooted in late 2008, the 26-nation bloc extending from Egypt to South Africa would initially operate as a free trade area, eventually transforming into a full customs union.

For foreign investors, the EAC common market is a mouthwatering prospect. With a relatively youthful population of almost 130 million people, the prospect of free trade throughout the five nations and a determination to promote rapid economic growth, the bloc presents corporations with a rare opportunity to get a foothold in a frontier market that is rapidly modernizing. Mbuvi believes it will significantly benefit companies already established in the region and newcomers alike: “The EAC common market is a huge development because it helps us easily pool a single management structure across the region. For our customers, doing business across the region becomes more homogenous, so transaction costs come down,” he explains. “It’s easier for them to set up in one country and service the others, so they can set up in the country that has the most advantages for them.”

For Kenya, however, the EAC common market is a mixed blessing. Although it is already clearly the regional economic leader, Kenya is also relatively expensive. As barriers come down, companies may find it makes sense to set up in a neighboring country rather than shoulder the potentially higher costs of operating from Kenya. Similarly, Kenya’s massive investment in its transportation and communications infrastructure will make it easier for companies to move goods and people around the region, so setting up an operation in, say, landlocked Burundi becomes significantly less difficult.

Mary Kimonye, CEO of Brand Kenya, the organization charged with building Kenya’s profile on the world stage, is well aware of the potential competition: “For a long time, anyone who wanted to set up in Africa would set up in Nairobi,” says Kimonye, “but now our neighbors are coming up, other regions are coming up, and we are in competition with them. We need to up our game to continue to compete,” she says.

Part of Brand Kenya’s goal is to raise the profile of Kenya’s products worldwide and to raise awareness among consumers that they might already be buying Kenyan products. Few people, for example, realize that as many as a third of the roses sold worldwide come from Kenya’s farms and that much of the coffee they drink is Kenyan. “We export some of the best-quality tea and coffee in the world, but our products go out in bulk, so they lose originality,” says Kimonye. “When people drink coffee in Starbucks, rarely do they appreciate that their coffee might be from Kenya.” Brand Kenya’s efforts may be paying off already, however, with Kenya’s coffees coming top in an October Consumer Reports test of beans from around the world.

Neighborhood Watch

In raising its profile globally, however, Kenya still has a mountain to climb. For many people the word “Kenya” still conjures shocking images of the violence that erupted after the general elections in 2007 and left more than 1,200 people dead. “Many people around the world do not have any clear perspective on Kenya,” admits Kimonye. She says people’s perceptions of Kenya are also tainted by their impressions of Africa as a whole, which, she believes, is often considered to be “riddled with corruption, disease, poverty, child soldiers, strife, conflict and issues of malnutrition.”

Kenya’s neighbors also have an impact on the country’s image. “We are very conscious that it is not possible for us to think about our image without thinking about what is happening in our neighboring countries,” Kimonye acknowledges. “That is the reason why Kenya becomes very active in the peace processes in the region.”

According to Kennedy Kihara, senior deputy secretary in the president’s office, Kenya’s leaders also feel a sense of obligation toward their neighbors. “We have a responsibility in this region, of which we are keenly conscious,” Kihara says, adding that the government is also conscious of the instability in some of the countries bordering Kenya and is working to promote peaceful solutions to the conflicts in the region. “We are responsible to try to bring peace to [our neighbors],” he explains.

|

|

Hello world: Kenya’s modernization efforts are transforming the country |

While Kenya’s policymakers are mindful of the risks, they are confident that the country’s advanced infrastructure will be a boon for the economy. This investment is “absolutely about capturing the increasing trade from Asia into East Africa and beyond,” says Equity Bank’s Mwangi. “There is a 94% correlation between the growth rate of China and Kenya because of the unique strategic location of Kenya. China may not be picking the mineral resources out from Kenya, but it all passes through Kenya and has a consequential effect on our economic growth.” The construction of the new $16 billion state-of-the-art container port at Lamu on Kenya’s northeast coast is a case in point. “Building Lamu Port is not for Kenya; it’s purely dedicated to make Kenya the only gateway to Africa,” Mwangi asserts. “We have the oil from Uganda, the minerals from Congo, we have trade from Ethiopia and Eritrea, the oil link from Sudan to Kenya—all will pass through Kenya. The service industry for all those countries will be in Kenya,” he adds.

Fair’s Fair

Kenya is becoming a regional pioneer in another area: ethical business. According to Harriet Lamb, London-based executive director of the Fairtrade Foundation, many of Kenya’s businesses are already Fairtrade-certified, which means they conform to minimum environmental, social and economic standards and maintain a clear focus on the welfare of their workers. With the rapid growth of intraregional trade, particularly on the back of the EAC’s common market, both Kenya’s fair trade advocates and the country’s political leaders are hoping the country will become a model for the whole region—as well as an acknowledged leader in the promotion of ethical business.

Some of the core elements of Kenya’s mission are already closely aligned with the Fairtrade goals, with their clear emphasis on humane working conditions, fair pay and environmentally and socially responsible business practices. “The principles on which Fairtrade is based are also good for the ordinary Kenyan,” says Michael Kwame Nkonu, Nairobi-based executive director of the Fairtrade African network. “If Kenya, through its agricultural policies, adopts some of the policies that we have put in place, it will make it easier for them to market their products globally.” Brand Kenya’s Kimonye agrees, adding that the government is keen to promote fair trade as part of its efforts to raise the country’s profile.

Kenya’s efforts to establish itself as a powerful, recognizable global brand may be paying off, but backing that brand with a strong, sustainably growing economy is another challenge entirely. While it is broadly supportive of Kenya’s strategy, the IMF cautions that the scale and pace of change under way in Kenya is so great that it has “created an uncertain environment, particularly as viewed by potential investors, visitors and clients outside Kenya.” The multilateral also warns that external factors, such as the continuing fallout from the global financial crisis, may hinder the country’s development. George Outa, communications adviser in the office of the prime minister, counters the IMF’s assertion: “There is not a single doubt that Kenya is on a major upward trend. That is a fact. There is no question that we are in an historic moment.”

For the sake of the country’s potential investment partners, Kihara puts it more bluntly: “This is an economy that is about to take off in a big way.”