AGAINST ALL ODDS

By Justin Keay

Mid-20th-century tourists flocked to Lebanon, the Switzerland of the East. War and instability long ago changed that. Now, with the Syrian conflict spilling over its borders, the country faces yet another round of political and economic challenges.

|

| Palestinian Syrian refugees receive humanitarian aid at the Baddawi refugee camp in northern Lebanon |

| photo credit : REUTERS/STRINGER |

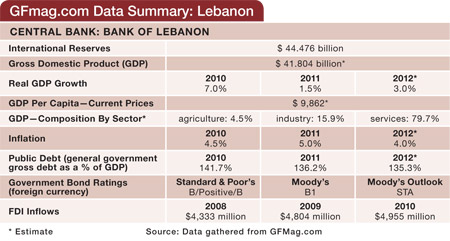

Lebanon is no stranger to instability—indeed, it has known little else since the 1970s—but a string of events in recent months has made things worse than usual. Outbreaks of fighting in the capital, Tripoli, a spate of kidnappings and, of course, the ongoing descent of its neighbor Syria into civil war, are merely adding to the long list of political and economic problems that the country faces. In September, ratings firm Standard and Poor’s concluded that Lebanon was the most exposed of Syria’s neighbors to “external, fiscal and political risks stemming from the conflict.” Little wonder that the Institute of International Finance predicts Lebanon will grow only 1.2% this year against 1.8% last year, blaming “the continuing adverse effects of the [Syria] conflict on economic activity through lower transport trade, the ongoing decline in tourist arrivals and weak investment.” Barclays echoed this in a recent report, lowering its forecast to 1.8% and suggesting the fiscal deficit would reach 7.5% of GDP (against 4.3% in 2011) and the debt-to-GDP ratio, just under 136%.

Old problems have not gone away. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Survey now places Lebanon 144th out of 144 countries for quality of electricity supply—reflecting its still-war-damaged infrastructure. It ranks Lebanon 142 out of 144 for public trust in politicians—a direct indicator of the faction-ridden political scene. The government headed by millionaire businessman, Najib Mikati, is seen as largely ineffectual and one reason why external debt increased by almost 10% year-on-year to reach $23 billion at the end of July 2012.

For the IMF and other market watchers, the biggest concern is policy inaction. “Lebanon is more affected by the slowdown in investment due to policy paralysis and less so than from the direct effect from Syria,” the IMF concluded in a recent report.

That said, the descent into civil war in Syria—a country to which Lebanon was joined until 1920—has had a dramatic indirect effect, with FDI and consumer confidence both virtually at a standstill.

The all-important tourism industry—which accounts for almost 30% of GDP—is having its worst year in memory. Although visitor numbers from Syria have held up, thanks to refugees fleeing the fighting, many Syrian refugees have little money, while the business that cash-rich visitors from the West and the Gulf usually bring has all but dried up. Nassib Ghobril, chief economist at Byblos Bank, says tourist arrivals declined by 34% in the first seven months of 2012, compared to the last “normal” year, 2010.

LOW EXPOSURE

Officials, however, are keen to emphasize the positives. Central bank governor, Riad Salameh, says that, compared to most other Arab countries that have been affected by the uncertainty surrounding the Arab Spring, Lebanon’s outlook has been partially redeemed by the continuing strong performance of the banks. “We have maintained confidence despite the adverse economic environment, with bank deposits this year expected to grow 7% to 8%; the currency is stable, and the interest rate structure is holding up well,” he says.

Salameh points out that the exposure of Lebanon’s banks to Syria—once around $5 billion—now stands at only $2.2 billion. He says the country’s 26 financial groups have been successfully put through stress tests, are ahead of schedule in preparations for Basel III capital adequacy requirements and meet the central bank’s stringent leverage and liquidity requirements. They are lending more to industry, according to Salameh, with loans to the private sector now taking almost 40% of bank resources. “Lebanon has been through many crises, but its banks have shown resilience, and I am confident we will get though this period,” he insists.

“The Lebanese banking sector remains the backbone of the Lebanese economy and continues to be profitable, highly liquid and well capitalized”

– Nassib Ghobril, Byblos Bank

Saad Azhari, head of Blom Bank, agrees: “I think the Lebanese banking system has enough experience, capital potential, resiliency and liquidity to tackle the challenges facing it.” The big question is what will happen to the broader Lebanese economy—and Lebanon itself—over the coming months. Freddie Baz, head of Bank Audi, reiterates the widely held view within Lebanon that the impact of the Syrian crisis so far has been mainly psychological and a reflection of the fact that the 360-kilometer border between the two countries was always Lebanon’s gateway to the Arab hinterland.

“Capital flows between us were always almost nonexistent,” Baz says. “Syria is not an important partner in terms of trade, monetary or human flows.” But he adds that fears of a spillover have affected tourism and investment decisions. He also defends the government against accusations of inaction, saying their main responsibility right now is to “preserve economic and political stability.”

Despite the challenges, Baz remains positive. Business is booming for Bank Audi. Egypt looks stable and resilient with activity in “growth mode,” and at the end of September the bank got a license to operate in Turkey, a development he sees as having huge potential. In difficult times the Lebanese—an international, entrepreneurial people with long trading and banking traditions—have always looked outward to the world beyond their difficult region. Perhaps that is the answer again this time.

DYNAMIC BANKING SECTOR

How can a country with a barely functional government comprising rival political factions and situated in one of the world’s most dangerous neighborhoods—next to a country descending into civil war—have such a dynamic banking system? Lebanon’s financial sector has held up remarkably well, as it did during the civil war of the 1970s and 1980s, the Syrian occupation of the 1990s and the 2008 to 2010 global financial crisis when inflows increased by more than 20%. Recent figures from the central bank show profits of the top 12 banks increased 8% to $837 million in the first half of 2012, and deposits continued to rise, thanks to wealthy Lebanese expatriates who retain trust in their country’s bank system despite all the crises besetting the wider economy.

“The Lebanese banking sector remains the backbone of the Lebanese economy and continues to be profitable, highly liquid and well capitalized,” says Nassib Ghobril of Byblos Bank.

According to Mohamad Chatah, a former minister of finance and senior foreign policy adviser to former prime minister, Saad Hariri, this continued buoyancy reflects the exceptional nature of the bank sector and of the Lebanese who manage it. Speaking in mid-September at the Aspen Institute in Washington, DC, Chatah pointed out that the overall assets held in the sector—where around 60% of transactions are dollar-denominated—is equivalent to 350% of GDP, or $140 billion, against GDP valued at around $40 billion. Most inflows come from expats, who equal a quarter of the domestic labor force but are much richer.

“Lebanon has been through many crises, but its banks have shown resilience”

– Riad Salameh, Lebanon Central Bank

Why the appeal? Lebanese banks are well run—mostly by families who have a vested interest in its wellbeing—and well regulated, with central bank governor Salameh overseeing a comprehensive regulatory network that has prevented any large-scale emergence of toxic debt, according to Chatah. “The banks and the central bank have been and remain very conservative. Traditional rules have always prevailed,” he said, adding that Lebanese banks remain resilient in the face of a deteriorating global financial situation.

But the sector is now facing its most serious challenge in a generation. Ghobril sees several contributing factors, including economic stagnation, the Syrian crisis, deterioration in domestic security conditions, shrinking margins, historically low global interest rates, the rise in operating costs due to government-mandated salary adjustments, and the still-elevated borrowing needs of the government.

Plus, with international pressure growing on Iran over its nuclear program, and Syria’s civil war spreading to its main cities, there are fears that inflows from these two pariah countries could undermine Lebanon’s reputation for financial probity.

The ongoing money-laundering case against the now-defunct Lebanese Canadian Bank (LCB) hasn’t helped–– in August, the US seized $150 million from LCB, alleging that Hezbollah was using the bank to launder money from drug running and other global operations. Neither has the fact that Hezbollah—branded as a terrorist organization by the US—is part of the government and has strong links with the regimes in Teheran and Damascus. The hostile global mood against bank secrecy anywhere, as the Swiss will attest, is another risk factor.

“Whilst we recognize Lebanon’s bank sector is an important area of stability and we support that, … we need to recognize that it is characterized by secrecy, [which] when combined with the realities of the neighborhood, lead to issues we need to take seriously,” said Daniel Glaser, assistant secretary for terrorist financing at the US Treasury Department.

Although Glaser stresses the US’s intention of working with and alongside the Lebanese authorities, he said they must take seriously infractions by Hezbollah, Syria and Iran.

But Chatah is confident the sector will survive this crisis, as it has previous ones. Pointing to new rules that require tougher audits and closer scrutiny of the origin of deposits, effectively strengthening the hand of Lebanon’s Special Investigations Commission in fighting money laundering, he says Lebanese banks cooperate fully with other jurisdictions. He also says that Syrians and Iranians find it almost impossible to open bank accounts in Lebanon. “Lebanese banks are obliged to follow US rules or risk having their license cancelled by the central bank,” he says.

What is clear is that Lebanon’s banks are in this together: Confidence is a fragile thing and, once gone, is hard to get back. Coupled with the sector’s being vital to financing the government deficit and thus Lebanon itself, banks have a strong incentive to continue towing the international line.