Following nearly five hard years of negotiations, Canadian PrimeMinister Stephen Harper on October 18 signed a Canada-European Unionfree trade agreement in Brussels.

Although the agreement in principle got scant attention outside of Canada, the pact is, in fact, a big deal. For starters, the new setup is expected to lead to a 20% increase in bilateral trade and boost Canada’s GDP by $12 billion. What’s more, its also expected to become the template for a US-EU trade agreement. Negotiations for the latter began earlier this year. An agreement would create the worlds biggest free-trade zone.

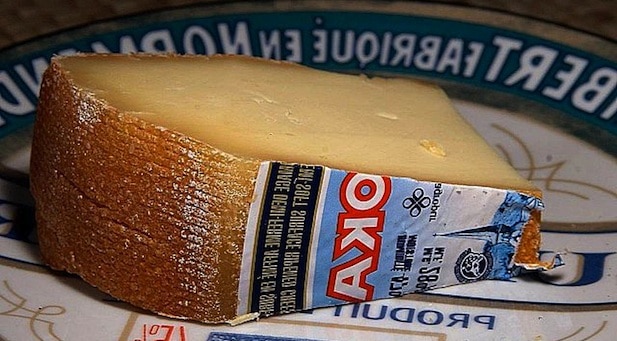

The Canada-EU deal might in the end be sunk, however, because it would allow more than 13,500 additional tonnes of camembert from Normandy, gouda from the Netherlands and Parmigiano Reggiano from Italy into the Canadian market each year, thereby crowding out the domestic stuff.

Fully half of Canadas cheese is made in the French-speaking province of Quebec. And federal opposition leader Thomas Mulcair, a socialist from Quebec who has been open to trade agreements, vowed that he wouldnt allow Canadas cheesemakers and dairy farmers to be thrown under the bus. A number of labor unions and environmental groups have already come out against the tentative agreement.At this point, Mulcair has yet to offer his pronouncement on the pact,noting that he has not seen the full text of the agreement. “We’re notbuying a pig in a poke,” he said in a recent interview.

But one thing is clear: The agreement would be great news for Canadianmanufacturers in the industrial heartland of southern Ontario, who have in recent years seen a hollowing out of the auto industry, and for Canadian beef and pork producers in western Canada, who will be allowed to boost their exports to bifteck-frites crazy France and other EU countries by some $600 million a year.

The agreement is expected to create some 80,000 new jobs in Canada. Moreover, Canadas cheese machine already gets plenty of breaks from the government. The Dairy Farmers of Canada represents about 12,500 members and their sector is insulated from foreign competition by outrageously high tariffs on imports. Those levies exceed 200%.

This has created a raw deal for Canadian consumers. Despite a vibrant domestic dairy industry, consumers in Canada pay perhaps the highest cheese prices anywhere in the G7. Consumers in Canada routinely pay at least $9 for a pound of Gouda. In Amsterdam, an arguably superior product costs half that.In fact, competition is exactly what Canadas cheesemakers need if they are ever going to make a decent product that can hold its own in the global marketplace, just as Canadian ice-wine producers have done.

But will the countrys francophones stick it to the Anglos again? In theory, leaders in Quebecwho have so far been conspicuously mum on the subject of closer ties with Europecould kill the most important FTA Canada has signed since NAFTA. Thats because the agreement needs the approval of all 10 provinces to pass muster.

Still, the whole thing smacks of a strange kind of, well . . . Canadianism. Apparently, Canada doesnt mind having its economy bought out by foreign interests from the US, the UK or Brazil. But threaten the countrys Oka-makers and youre in for a fight.