As economies start to grow again, central bankers face the tricky question of when to ease off the gas—or even tap the brakes.

The last year kept central bank governors on high alert, as a global health crisis threatened fiscal as well as physical health. Although years of loose money left some with little room to add stimulus, central bankers used all the tools at their disposal to mitigate the immediate threat. Covid-19 has since played a role in a cascade of aftershocks, including a slump in commodities and a collapse in employment. It is even now evolving unpredictable variants. Yet signs of growth are emerging—albeit uneven and unevenly distributed.

“The pandemic is still underway and high uncertainty persists, making it too early to tell which shocks are transitory and which are permanent,” says Alejandro Díaz de León, Governor of the Bank of Mexico (interview, p. 25) “Global and local supply chains remain critically affected and may be subject to a profound adjustment process.”

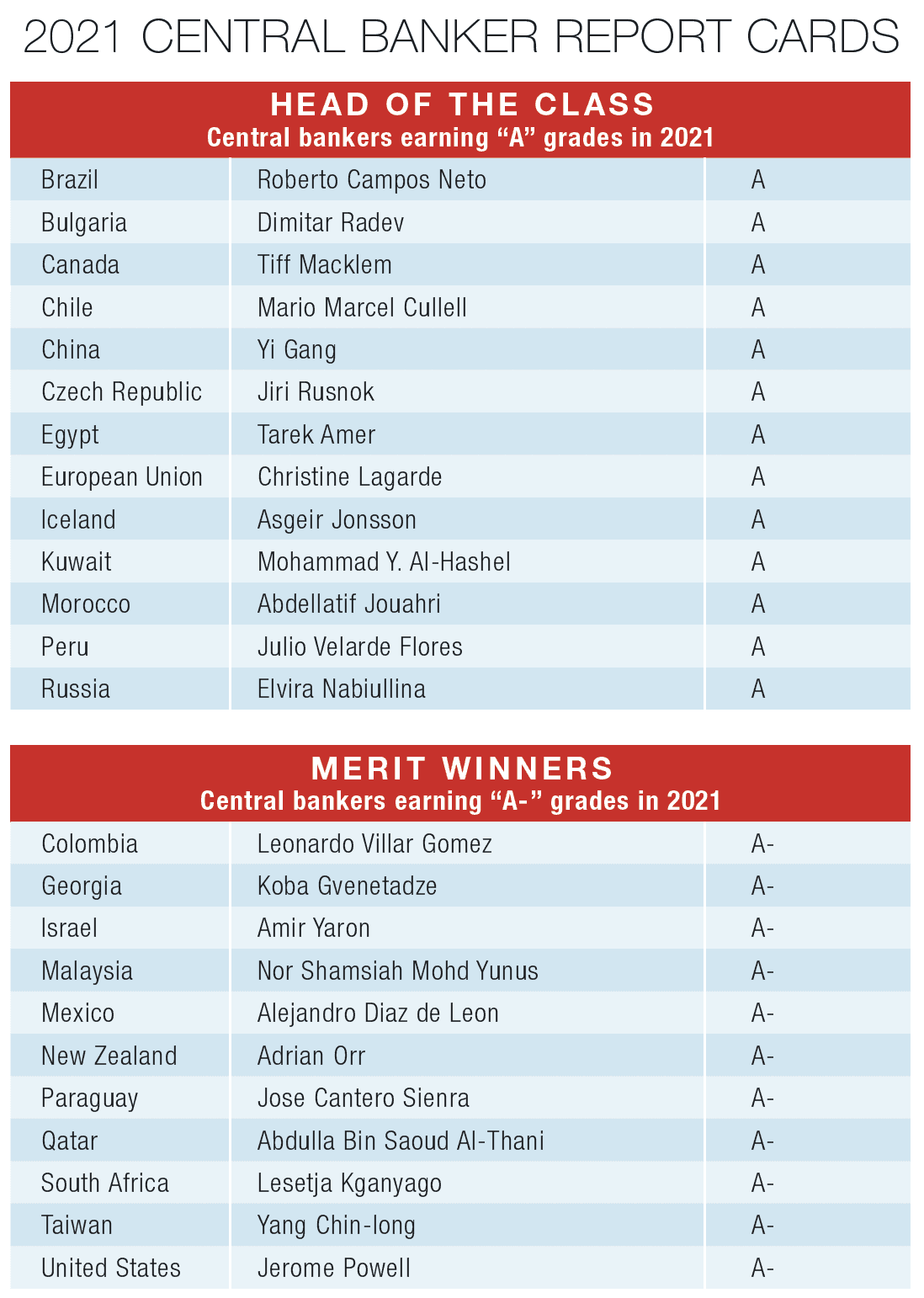

Against this backdrop, Global Finance presents its 27th annual Central Banker Report Cards, in which we grade the top leaders at approximately 100 central banks around the world. Over the past year and looking ahead, they central question for central bankers will be if and when to shift from bolstering economic activity to tapping the brakes.

“We have learned from experience that patience is needed to avoid premature policy adjustments,” says Yannis Stournaras, Governor of the Bank of Greece (interview, p. 31) “In fact, we have made explicit that our commitment to avoid a premature tightening may imply temporary periods of above-target inflation.” Stournaras, along with many independent economists, views current inflation as transitory. “Central banks should look through this temporary jump,” he counsels.

Conditions are certainly not equal across the board, with less mature economies facing significant long-term risk from lost infrastructure and green field investments. “Emerging market economies will face the additional challenge of dealing with the monetary stimulus withdrawal in advanced economies,” notes Mexico’s Diaz de Len, “which could translate into periods of volatility and tighter global financial conditions.”

Methodology

Global Finance editors, with input from analysts, economists and financial industry sources, grade the world’s leading central bankers on a scale of A to F, with A being the highest grade and F the lowest, based on a series of objective and subjective metrics, including the appropriate implementation of monetary policy for the economic conditions of each country. Judgments are based on performance from July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021. A governor must have held office for at least one year in order to receive a letter grade.

We apply an algorithm to increase the cohesion of the grades between the different geographical areas, with 100 signifying perfection. The proprietary algorithm includes criteria—such as monetary policy, supervision of banks and the financial system, asset purchase and bond sale programs, accuracy of forecasts, quality of guidance, transparency, independence from political influence, success in meeting specific mandates (which differ from country to country), and reputation at home and internationally—weighted for relative importance.

PROFILES BY REGION

The Americas | Latin America | Europe | Asia-Pacific | Middle East & Africa

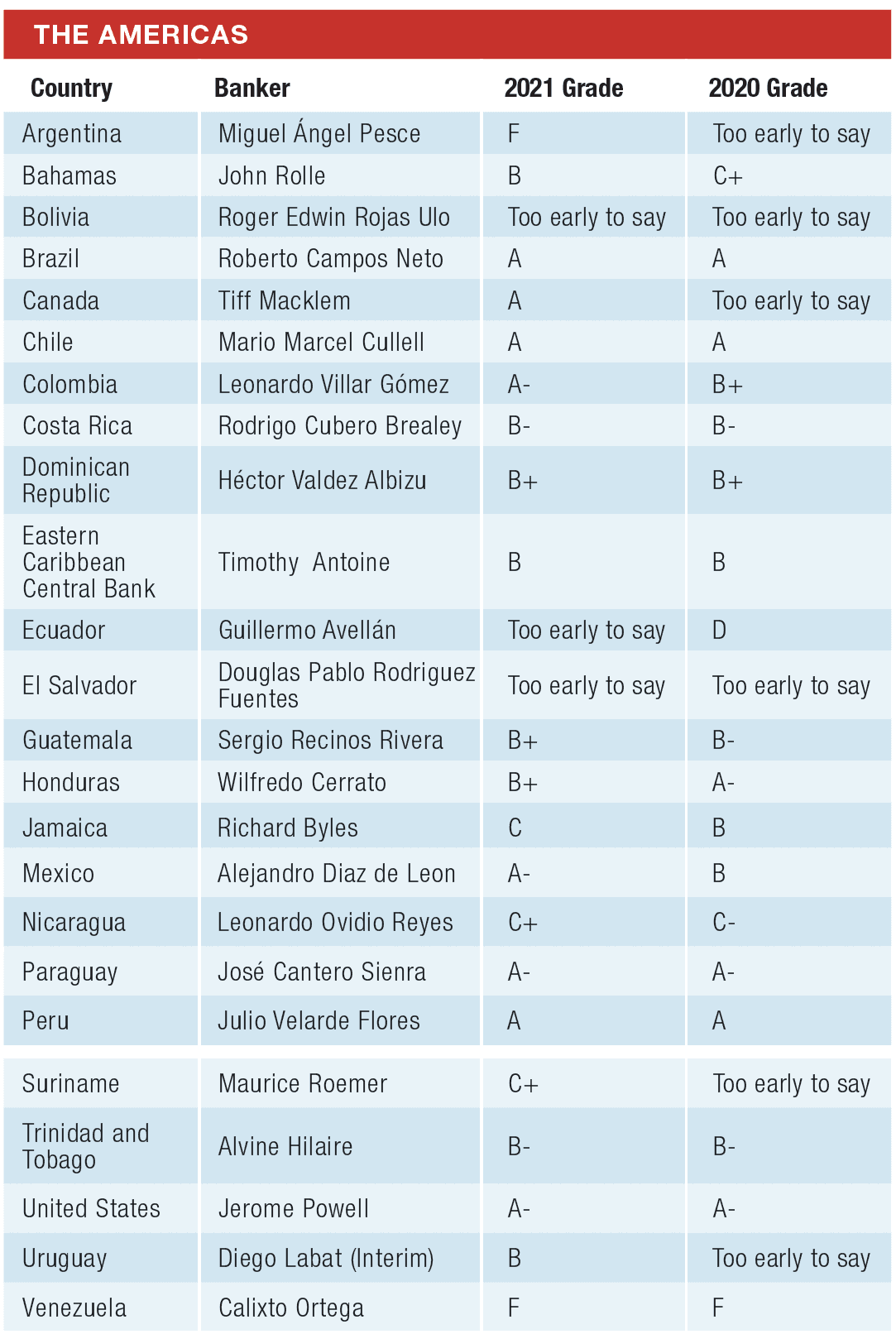

THE AMERICAS

ARGENTINA

Miguel Ángel Pesce | GRADE: F

Argentina is experiencing a good recovery, with expected GDP growth of 6.4% in 2021. Despite soaring inflation—expected to reach 50%, up from 36.1% in 2020—the central bank is not expected to hike interest rates before midterm elections next month. Rather, as FocusEconomics economist Oliver Reynolds points out, the central bank has continued to finance the government’s deficit spending and tightened currency controls to prop up the peso amid talks with the IMF over a fresh bailout package. Those negotiations—also unlikely to get serious until after the elections—add to the uncertainty.

“Argentina’s central bank has been an outlier by ignoring the warning signs over inflation,” comments emerging markets economist Nikhil Sanghani at Capital Economics. Reynolds adds that the central bank continued to finance the government’s fiscal deficit in response to market aversion. “We are not optimistic about prospects,” he concludes. “Inflation is set to stay well in double digits, and the peso will continue to crumble, despite the efforts of the government and the central bank.”

BAHAMAS

John Rolle | GRADE: C+

With the Bahamian dollar pegged one-to-one to the US dollar, the main challenge for the Central Bank of the Bahamas and Governor John Rolle has been to keep control of external reserves, put under stress by Covid-19. In May 2020, the central bank removed all long- and short-term exposure limits on banks’ reserves to force commercial banks to supply larger quantities of foreign currencies from their own resources instead of relying on the central bank; but as of July 2021, it had reimposed a $5 million foreign exchange “ceiling” exposure—a decision seen as a return to normal.

In a different field, the Bahamas last year became the first nation to issue its official currency in digital form. The “Sand Dollar” will be used across the Atlantic Ocean archipelago of more than 700 islands, where not everyone accepts credit cards, the presence of physical banks is not massive, and weather disasters call for flexibility in payment options.

BOLIVIA

Roger Edwin Rojas Ulo | GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Bolivia’s central bank has hewed to an expansive stance even as social and political instability took hold in 2020, with tensions heightened by the health crisis. Liquidity infusions and solid exchange-rate management have kept inflation well in check, giving the bank “space to remain dovish” next year, according to economist Stephen Vogado of FocusEconomics. “The bank should maintain its accommodative stance going forward, as the economy begins to show signs of recovering from last year’s downturn.”

BRAZIL

Roberto Campos Neto | GRADE: A

It was only in February, following a 30-year debate in Congress, that the Central Bank of Brazil was officially granted “technical, administrative and financial autonomy.” Going forward, Brazil’s central bank governors are legally protected from being fired for differences with the executive and entitled to a four-year mandate, renewable once. The move shored up investor confidence. Governor Roberto Campos Neto, appointed in 2019, showed agility in responding to the fast-changing environment of the past year. Initially, the bank continued with stimulative policies such as reduced reserve requirements and eased lending rules for small to midsize enterprises—as well as rate cuts, even pushing the benchmark Selic rate to a record low of 2% in August. But in recent months, the bank deftly pivoted in the face of spiraling inflation, raising the Selic rate by 325 basis points (bps), “with further hikes being penciled in before year end,” according to Vogado.

CANADA

Tiff Macklem | GRADE: A

Since taking the helm at the Bank of Canada in June 2020, Tiff Macklem has continued the aggressive expansionary monetary policy of his predecessor, often noting the extraordinary current need for stimulus. “I think the challenge for central bankers, not just in Canada but also elsewhere in the world, has been to explain that because of the scale of this pandemic, and the hit to the economy, and the different impact to different parts of society—that they want to see all of that reverse before we even consider tightening policy,” says Stephen Brown, an economist with Capital Economics. “I think Macklem has done a good job in communicating this.” Macklem expanded the governing council from six to seven in order to bring another woman into the leadership team. Macklem gave the Bank of Canada an impeccable record during his tenure, and has gone above and beyond in explaining its monetary choices.

CHILE

Mario Marcel Cullell | GRADE: A

The Bank of Chile has long been considered an expert pair of hands in the management of monetary policy in Latin America. It did not disappoint during the Covid-19 crisis last year and this year. “Chile’s central bank has offered perhaps the clearest and most consistent communication of any central bank in the region over the past year. For instance, with inflation picking up and the recovery gathering steam, the central bank softened its forward guidance about keeping rates low earlier this year. Then, in its June Monetary Policy report, it explicitly signaled that a tightening cycle would soon begin; and it duly delivered a rate hike in July,” says Capital Economics’ Sanghani. “These clear communications will help to guide investors and economic agents over the coming months.”

COLOMBIA

Leonardo Villar Gómez | GRADE: A–

Colombia’s central bank kept its key rates at record lows to support the economy through the Covid-19 crisis and early recovery. It is now on the verge of resuming monetary tightening. At its July 30 meeting, the bank noted pressure building against its accommodative stance.

“[The bank] has tweaked its forward guidance to state there is limited scope to keep rates so low; and, unlike most others in the region, it has also focused on the growing fiscal risks in the country,” says Sanghani.

“Leading indicators suggest underlying momentum remained strong into the second quarter,” says economist Alexandros Petropoulos at FocusEconomics, which speaks well of the economic management through the crisis.

COSTA RICA

Rodrigo Cubero Brealey | GRADE: B–

The Central Bank of Costa Rica has kept its policy rate at an all-time low of 0.75% for 14 consecutive months to support economic activity. Despite a recent surge in inflation, the bank is expected to keep its policy loose also in the months to come. The risk is that it may remain behind the curve.

“The continued accommodative stance, combined with liquidity injections in the form of quantitative easing and preferential interest rate loans to affected firms, has helped to accelerate the economic recovery—with indicators for Q2 2021 hinting at improving conditions. Going forward, a still-fragile recovery coupled with a persistent output gap will likely prompt the CBCR to maintain its accommodative stance in the final stretch of 2021. Moreover, although inflation picked up recently, the bank has attributed the increase to a low base effect and transitory factors,” comments economist Jonuel Pérez at FocusEconomics. “That says growth in activity is set to gain steam from Q2 onwards, which could lead price pressures to pick up toward year end and thus compel the bank to tighten in 2022.”

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

Héctor Valdez Albizu | GRADE: B+

One of the most dynamic economies in the region, the Dominican Republic benefits from a central bank with a solid reputation. The Central Bank of the Dominican Republic is seen as a steward of the currency, and its policies help support the country through the Covid-19 crisis.

“The bank’s measures, together with fiscal support from the government, have helped steady the ship,” says FocusEconomics’ Reynolds. “Private-sector credit is expanding sharply; and the economy is now back above its pre-pandemic level, making the Dominican Republic one of the region’s star performers.”

The DR’s relative economic health will make it possible for the central bank to phase out stimulus gradually. “Recent high inflation is a risk, though,” warns Reynolds. “If it leads to a deanchoring of inflation expectations, this could force the bank to tighten quicker than it would like to.”

EASTERN CARIBBEAN CENTRAL BANK

Timothy Antoine | GRADE: B

The Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) is the monetary authority for a group of eight island economies: Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.

Particularly badly hit by the collapse of tourism, the bank abandoned its goal to keep the EC dollar pegged to the US dollar; but it was not enough. Some countries, such as Antigua and Barbuda, are expected to contract further in 2021, after their GDP contracted in 2020 as much as 18%. In July, Antoine announced a new 2021-2026 strategic plan for recovery and resilience, including a new fund for renewable energy and a global plan to reduce carbon’s footprint.

Even so, the ECCB innovated, becoming the world’s first currency union central bank to issue digital cash, called DCash, on the heels of the Bahamas’ digital Sand Dollar.

ECUADOR

Guillermo Avellán | GRADE: Too early to say

On May 25, Verónica Artola Jarrín resigned from the management of the Central Bank of Ecuador, having been in office since June 1, 2017. Her replacement, Guillermo Avellán, is an interim appointed by President Guillermo Lasso Mendoza, as the laws around Ecuador’s central bank changed last spring. The new monetary board, formed in August, will choose the manager of the Ecuadorian central bank.

EL SALVADOR

Douglas Pablo Rodríguez Fuentes | GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

As US dollars are legal tender in El Salvador, its monetary policy is tied to that of the US and has been extremely accommodative since March 2020. In addition to fiscal stimulus, “additional measures were taken in a bid to support the economy after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, such as lower reserve requirements, a trust fund to support workers and relaxed lending conditions,” says Marta Casanovas, an economist at FocusEconomics.

“The economy is projected to rebound this year from 2020’s downturn. The recovery seems to be underway as GDP returned to growth in Q1, and data for the first two months of Q2 shows activity picked up further. The use of US dollars means that inflation is set to remain well anchored this year,” concludes Casanovas.

GUATEMALA

Sergio Recinos Rivera | GRADE: B+

Expansionary measures undertaken by the Bank of Guatemala (also called Banguat) during the Covid-induced recession of 2020 have been effective, with GDP rising above its pre-pandemic level in Q1 2021.

“The economy’s strong performance amid a notable firming of domestic demand, coupled with potentially higher price pressures, could give the bank reason to tighten its monetary policy stance ahead,” says Jan Lammersen, an economist at FocusEconomics. “However, premature tightening could derail the still-fragile recovery. Given the tightrope Banguat is walking, most of our analysts expect it to take a wait-and-see approach and hold rates steady for the rest of this year.”

HONDURAS

Wilfredo Cerrato | GRADE: B+

The Central bank of Honduras (BCH) was radical in its expansionary policy over 2020; but the economic momentum remains frail, and the bank has been only partially successful in bringing back growth.

Lammersen says that “the bank’s response, coupled with the government’s small, albeit well-targeted fiscal stimulus package, has been somewhat successful as the economy just managed to return to growth in Q1 2021. Looking ahead, the BCH will likely maintain an accommodative stance as underlying momentum remains frail. The key risk is uncertainty over the nature of inflation and whether higher price pressures will be transitory or permanent. Our analysts see inflation continuing to rise through next year, although if the bank tightens its monetary policy stance prematurely it risks throwing a spanner in the works for the economic recovery.”

JAMAICA

Richard Byles | GRADE: C

When Covid-19 hit, Jamaica’s central bank already had little room to maneuver: The policy rate was already close to all-time low. The bank left the overnight policy rate unchanged at 0.5% last year and in 2021. “The bank’s response, coupled with the government’s limited fiscal measures, has not been greatly successful, as recent data suggests that the economy remained in the doldrums in the second quarter of 2021,” says Lammersen.

Analysts do not expect many changes over the coming months. Jamaica’s central bank put itself in a hard spot, with few tools to boost the economy. “A premature tightening cycle would derail what is an already frail economic recovery, and it is likely not in the cards,” concludes Lammersen. “The tourism sector remains downbeat, weighing heavily on the economy; and lingering Covid-19 concerns should keep the bank on hold for the rest of the year.”

MEXICO

Alejandro Díaz de León | GRADE: A–

Outgoing Bank of Mexico Governor Alejandro Díaz de León was not confirmed with a second mandate by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, also known as AMLO. He will leave his post to current Finance Minister Arturo Herrera.

Now a lame duck, Díaz strove for central bank independence and was often seen as AMLO’s antagonist, which gave him credibility with international investors. His policy has not always been transparent. He surprised the market when in June he approved the first rate rise in more than two years, followed by another hike in August.

“The hawkish shift with a surprise 25-basis point rate hike in late June caught many analysts (ourselves included) off guard,” says Capital Economics’ Sanghani. Herrera, taking the helm in 2022, is expected to shift the bank in a more dovish direction.

NICARAGUA

Leonardo Ovidio Reyes | GRADE: C+

Nicaragua has a crawling peg against the US dollar. That limits monetary policy. However, the central bank cut its repo reference rate by 325 basis points to 3.5% between March 2020 and March 2021 and adopted other measures to help the economy, which was hit by hurricanes as well as Covid-19.

“A tighter labor market and extensive fiscal stimulus in the US have bolstered remittance inflows, buttressing spending,” says FocusEconomics’ Casanovas. “However, the recovery is still fragile, and data is flattened by a low base effect; so, the bank will likely continue its accommodative stance in the short term.” The governance problems that have characterized for some time the management of monetary policy in Nicaragua have not improved over the last year.

PARAGUAY

Jose Cantero Sienra | GRADE: A–

In the last 12 months, the Central Bank of Paraguay (BCP) has built on its tradition of stability and competence, helping the economy along with an expansive fiscal policy. The country’s economy has been relatively quick in returning to pre-Covid levels of activity.

The BCP upped its projections of GDP growth from 3.5% to 4.5%, despite recent low temperatures that have taken their toll on agricultural food output. The sectors with the greatest growth prospects for 2021 are construction, with 14%; livestock, with 12%; trade, 9.5%; and manufacturing, 8.5%, the BCP reported. The governor continued and solidified the good reputation of the central bank, and this has played an important role in the economic recovery.

PERU

Julio Velarde Flores | GRADE: A

Over the last 12 months, the Central Reserve Bank of Peru respected its hard-won reputation for guidance and communication, first relaxing its policy during the pandemic and then starting to tighten up as soon as rebound signs emerged. “Peru’s central bank has been prudent and cautious during the pandemic,” says Sanghani. “It has maintained an ultraloose monetary stance as the economy was hit hard last year and the beginning of this year from severe virus waves and lockdown measures—and it has looked through above-target inflation in the past few months as it prioritized supporting the economic recovery.” Building on the good reputation and credibility of the Peruvian central bank, its monetary policy made an important contribution to economic recovery.

SURINAME

Maurice Roemer | GRADE: C+

The central bank still lacks monetary policy flexibility, transparency and reputation—the former governor is being prosecuted for embezzlement. But one big step this year was the June float of the Surinamese dollar, tied to a deal reached in April with the IMF. The country receives a three-year, $690 million loan, but its currency was devalued by around 33%. In the past, Suriname has repeatedly defaulted on its heavy debt load, which is above 150% of GDP.

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

Alvin Hilaire | GRADE: B–

The Central Bank of Trinidad and Tobago cut interest rates last year in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The transmission of the laxer monetary policy has, however, been slow; and the economy is only now rebounding: IMF estimates put 2021 GDP growth above 2%—after a contraction of almost 8% in 2020. “We are at a delicate juncture,” Governor Hilaire said at a presentation of the bank’s 2020 financial sustainability report.

UNITED STATES

Jerome Powell | GRADE: A—

Since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, the US Federal Reserve has done whatever was in its power to face the Covid-caused recession with speed and intensity and to avoid a meltdown in the financial markets.

Over the last 12 months, the Fed missed one main point: The US economy did much better than was initially expected, so its forward guidance to keep its policy highly accommodative for three years made less sense than it had at the beginning of the pandemic. The risk is that an inflation may become ingrained in the economy over a longer term, but that possibility still appears remote.

“The Fed has been in the back seat for the past year, with the job of supporting the economy falling to fiscal policy,” says Michael Pearce, a senior US economist at Capital Economics.

“I don’t think we can blame the Fed for missing its inflation and maximum employment goals this year. It’s been rightly focused on doing all that it can to support the economy during the worst stages of the pandemic and is now pivoting back towards normalizing policy again,” he says.

URUGUAY

Diego Labat | GRADE: B

Uruguay, known for high inflation, in September 2020 changed its focus from the money supply to the monetary policy rate. It reintroduced a benchmark interest rate at 4.5%, in line with the overnight rate, in an effort to keep a lax monetary policy and support the economy over the pandemic. In August 2021, the bank increased the benchmark policy rate to 5% in its first tightening. Economists expect the new policy stance should tamp down price pressures.

VENEZUELA

Calixto Ortega | GRADE: F

The Central Bank of Venezuela did not change its policy over the pandemic and continues to battle the “twin evils of rampant inflation and unrelenting currency depreciation,” according to FocusEconomics’ Vogado. Although “the increasing dollarization of the economy has helped stem price pressures somewhat,” he adds, “the bank’s continued practice of printing money to finance the fiscal deficit ensured that annual inflation remained at four-digit levels throughout 2020.”

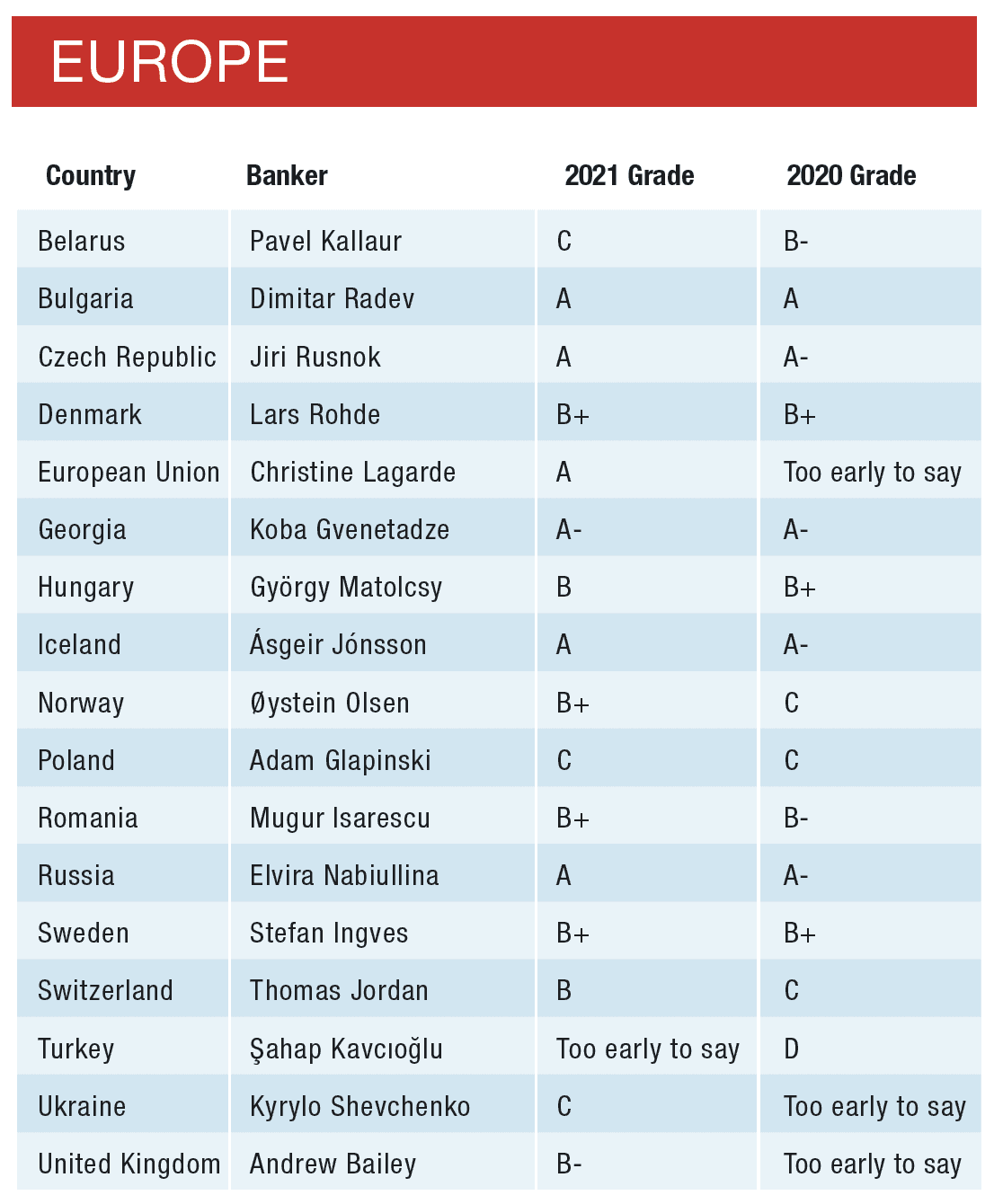

EUROPE

BELARUS

Pavel Kallaur | GRADE: C

Against a backdrop of negative economic growth and higher domestic inflation expectations, Belarus’ central bank did not waste any time in raising interest rates this year. Two rate rises, one in April and one in July, saw the policy rate jump from 7.75% to 9.25%. The central bank cited rising global commodity prices as the reason for its hawkish outlook. The IMF predicts inflation in Belarus will reach 6.9% this year, up from 5.5% in 2020. Kallaur showed his mettle when it comes to tackling inflation, but his hawkish stance has done little to boost the country’s sluggish economy. Economic growth has been in negative territory since the onset of the pandemic. The IMF predicts a 0.4% contraction this year for the oil-based economy.

BULGARIA

Dimitar Radev | GRADE: A

Radev ensured there was no stagnation in lending during the pandemic and prepared the economy for adoption of the euro. He acted swiftly and decisively to spur bank lending and enhance liquidity by implementing a package of measures to strengthen banks’ capital and liquidity positions. The base rate has stood at 0% for the past 12 months. In May, ING analysts pointed to a “robust recovery in consumption and exports,” which saw Bulgaria’s economy expand by 2.5% in the first quarter versus the previous quarter, almost back to pre-pandemic levels. The IMF predicts GDP growth of more than 4% this year, compared to -4.6% in 2020. In 2020, Bulgaria entered the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, which brings it a step closer to adopting the euro.

CZECH REPUBLIC

Jiří Rusnok | GRADE: A

Rusnok did not waste any time in providing clear guidance to markets, his intolerance for rising inflation, which exceeds the central bank’s 2% target range. In August, the central bank increased the two-week repo rate by 25 bps to 0.75% and increased the Lombard rate by 50 basis points to 1.75%. It kept the discount rate unchanged at 0.05%. In April, according to ING Bank, inflation increased to 3, as a result of higher fuel and food prices. The bank is expected to continue raising interest rates at a swift pace as the central bank believes inflation constitutes a bigger risk to the Czech economy than new coronavirus variants.

DENMARK

Lars Rohde | GRADE: B+

While Denmark’s economy contracted by more than 2% last year, it has almost returned to pre-pandemic levels, and the IMF predicts 2.6% GDP growth for this year. According to a June 2021 IMF Executive Board update, the fixed exchange rate policy with the euro area has served Denmark well, providing a framework for low and stable inflation. Rohde introduced negative monetary policy interest rates in 2012 to maintain links with ECB monetary policy. Expansionary fiscal policies also kept households and companies afloat during the pandemic, but with housing prices surging since last summer, Rohde believes now is the time to tighten fiscal policy. However, there is no indication of him doing the same with monetary policy, as he remains a staunch defender of the euro peg.

EUROPEAN UNION

Christine Lagarde | GRADE: A

Lagarde’s outspokenness on a wide range of issues–climate change and digital currencies–hasn’t always made her a favorite with traditionalists who believe central bankers should stick to their knitting. However, she has instigated the European Central Bank’s first Strategy Review since 2003 and has helped head off a pandemic-induced economic crisis in the eurozone with the ECB’s substantive Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) and the decision last year to reduce the bank deposit rate to a low of minus 0.5% to help shore up bank lending to companies and households. Key economic data suggests the ECB’s dovish outlook is paying off, with GDP in the second quarter of this year increasing by 2.2% in the euro area compared with the previous quarter. Employment also increased by 0.7% in the second quarter compared to the previous quarter. The ECB’s strategic review saw it firmly commit to an inflation target of 2%, but Lagarde doesn’t concern herself with transitory inflation trends–not enough, at least, to start contemplating rate rises.

GEORGIA

Koba Gvenetadze | GRADE: A–

Gvenetadze remained vigilant and decisive against rising and stubbornly high inflation, instituting several rate hikes throughout this year as inflation came in well above the central bank’s target range of 3%. The IMF said it welcomed the National Bank of Georgia’s “appropriate increases in the monetary policy rate in March and April” to help mitigate the inflationary impact of commodity price increases and supply constraints. Gvenetadze is determined to ensure inflation remains anchored around the bank’s target. In August, the policy rate was raised again to 10.0% as inflation reached almost 12%. Georgia’s economy was hit hard during the pandemic, shrinking by 6.2% in 2020 and 4.5% in the first quarter of this year. However, Gvenetadze credits the bank’s timely monetary policy during the pandemic with its ability to secure financial assistance from external donors.

HUNGARY

György Matolcsy | GRADE: B

The IMF praised Hungary’s central bank, Magyar Nemzeti Bank, for its swift response and the range of measures it took to ease market pressures during the pandemic last year. “It provided ample liquidity through a variety of policy tools, including FX liquidity swaps, enhanced lending facility, the expansion of its asset purchase programs (APPs), which includes government, corporate and mortgage bonds, and the adjustment of the policy rate,” the IMF staff stated in a May 2021 report. It’s measures such as these that helped the economy rebound, with GDP expected to increase by more than 4% this year, after contracting by more than 3% last year. The economic rebound hasn’t stopped Matolcsy from instituting a series of rate hikes. While some central banks in Central & Eastern Europe don’t want to raise rates too soon and jeopardize economic recovery, Hungary was one of the first European countries to hike rates this year in response to rising inflation, with the latest increase coming in August.

ICELAND

Ásgeir Jónsson | GRADE: A

Jónsson is one of a rare breed of central bankers who hasn’t had to resort to quantitative easing or negative interest rates to get his country through the pandemic, which dealt a blow to its tourism-reliant economy. During the pandemic, he indicated he was willing to do whatever it took to support financial stability and economic growth. He even contemplated negative interest rates at one point, but in the end, he didn’t need to go that far. With the bank predicting GDP growth of 4% this year, compared to a more than 6% contraction in 2020, IMF executive directors commended Iceland’s handling of the impacts of the pandemic and its strong policy framework. But challenges remain on the inflation front. Jonsson waited to see if inflationary trends were persistent before launching a rate-hiking cycle in May, to keep inflation within the central bank’s target range.

NORWAY

Øystein Olsen | GRADE: B+

Olsen and Norway’s Norges Bank are among the most hawkish of central banks in developed markets. ING analysts expect it to institute a series of interest rate hikes, which could last into next year. Last year, the central bank cut rates on at least three occasions, but at its June meeting this year it indicated that the policy rate would be gradually raised from 0% starting from September. Olsen, who is due to retire in February next year, says low interest rates have contributed to speeding up the return to normal output and employment levels, which will help bring inflation back toward the bank’s 2% target. But risks and financial imbalances can build up in economies following a protracted period of low interest rates, so this is Olsen’s way of preparing markets for a more hawkish stance moving forward.

POLAND

Adam Glapiński | GRADE: C

Glapinski took a surprisingly relaxed wait-and-see stance, despite inflation reaching 5.4% year-on-year in August, the highest level in 20 years, according to ING analysts. In early September he told PAP Biznes, a Polish Media outlet, that the Narodowy Bank Polski takes inflation very seriously: “However, let me remind you that inflation may, from time to time, run above or below the inflation target, including also outside the defined band for deviations from the target due to macroeconomic shocks occurring in the economy. The monetary policy response to these shocks must be flexible, as it depends on their causes and an assessment of their sustainability.” With inflation still expected to remain around the 5% mark by the end of the year, Glapinski may be running out of flexibility soon when it comes to monetary policy responses.

ROMANIA

Mugur Isărescu | GRADE: B+

Romania’s economy was one of the fastest among EU countries to rebound from the global pandemic. The economy is predicted to grow by more than 7% this year, according to ING. But while it is doing better than expected, Isarescu has another battle on his hands: inflation. ING has revised its year-end forecast for headline inflation from 4.7% to 5.5%. While some of the inflationary trends in food, gas and electricity prices are beyond the central bank’s control, come year end, the expectation is that the central bank will need to start taking a firmer stance on monetary policy with a rate hike of at least 25 basis points. For now, however Isarescu needs to be convinced inflation is more demand-driven rather than influenced by external factors.

RUSSIA

Elvira Nabiullina | GRADE: B+

Nabiullina tried just about everything to get inflation as close as possible to the central bank’s 4% target range. She has been indulging in what some analysts have described as some aggressive rate hikes, more notably the 100-bps rate hike the central bank instituted in July, which brought the key interest rate to 6.5%. In July, non-food inflation was more than 7% year over year. However, unemployment has fallen, and economic growth returned to pre-pandemic levels in Q2 this year. At its September meeting, the central bank increased the policy rate again, this time by a less aggressive 25 basis points. The central bank is predicting that annual inflation will reach 5.7% to 6.2% in 2021, before inching back to 4.0% to 4.5% in 2022. Nabiullina does not rule out further rate hikes, but she is clearly looking to strike a balance between keeping inflation at a manageable level and not hampering economic growth.

SWEDEN

Stefan Ingves | GRADE: B+

Unlike other banks within the EU, Ingves hasn’t had to battle rising inflation. In 2020, to minimize the impact of Covid-19 on Swedish businesses and households, the Sveriges Riksbank expanded its bond buying program and maintained an ultraloose monetary policy by keeping the repo rate at 0%. It is a policy that largely appears to have worked, with Sweden’s economy faring much better than a lot of its European neighbors, although unemployment remains high at more than 8%. The pace of central bank bond purchases will gradually taper off over the coming months, and Ingves seems to be in no hurry to change his accommodative stance, with inflation still well below the bank’s 2% target.

SWITZERLAND

Thomas Jordan | GRADE: B

The Swiss economy rebounded strongly in Q2 2021, according to ING analysts, with GDP increasing by almost 2% quarter on quarter as the country’s economy emerged from lockdown. “At the end of the second quarter, the Swiss economy was 0.5% below its pre-crisis level of activity, an exceptional performance compared to neighboring countries,” ING analysts wrote in a September 7 research note. Inflation in Switzerland hasn’t recovered as quickly as it has in other countries. Analysts predict inflation will average round 0.4% this year, which is unlikely to lead to any major shifts in Jordan’s expansionary monetary policy stance, which is focused on ensuring price stability and providing ongoing support to the Swiss economy.

TURKEY

Şahap Kavcıoğlu | GRADE: Too Early to Say

The comings and goings of governors at Turkey’s central bank in the last 12 months has done nothing to allay concerns about its independence. Last November, President Tayyip Erdogan fired Murat Uysal who had presided over a declining lira, which went into freefall last year, at one point losing 30% of its value. Uysal was replaced with ex-finance minister Naci Agbal, who instituted substantial rate hikes, which saw the main policy rate increase to a staggering 19% to tackle high inflation. But five months into the job, Erdogan had enough of Agbal’s hawkishness, which many argued was needed to bring stability to the lira and tackle persistently high inflation. Agbal was replaced by Turkish politician and banker Şahap Kavcıoğlu.

UKRAINE

Kyrylo Shevchenko | GRADE: C

Shevchenko has had his work cut out for him since taking over governorship of the National Bank of Ukraine last July during a pandemic, global oil price shock and concerns about the central bank’s independence. But with the Ukrainian economy tapped to grow by approximately 4% annually in the 2021-2023 period, he now has a different battle on his hands: inflation. At the time of his appointment in 2020, Shevchenko said he saw his role was about enhancing lending to businesses in the real economy by cutting the key interest rate. But high inflation has forced him to backtrack on that promise. This year saw a series of rate hikes all aimed at getting inflation under control. He may also have to backtrack on another promise about maintaining the NBU’s “institutional independence.” Recent departures from the central bank’s licensing department raised concerns around decision-making becoming more centralized, which could potentially jeopardize reforms of the banking sector.

UNITED KINGDOM

Andrew Bailey | GRADE: B–

At the height of the pandemic in the UK in 2020, Bailey was preparing markets for the prospect of negative interest rates. But the UK economy showed remarkable resilience in the second quarter this year, with GDP growth of almost 5% following the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions. However, by July, rising Covid-19 cases and supply and labor shortages–caused by a mix of Brexit and post-pandemic demand and supply issues–saw the UK’s growth recovery stall. With inflation predicted to end the year at around 4%, some on the Monetary Policy Committee are itching for a rate rise sometime next year. However, Bailey is less panicked about inflation, which he sees as more of a transitory phenomenon. Let’s hope he’s right.

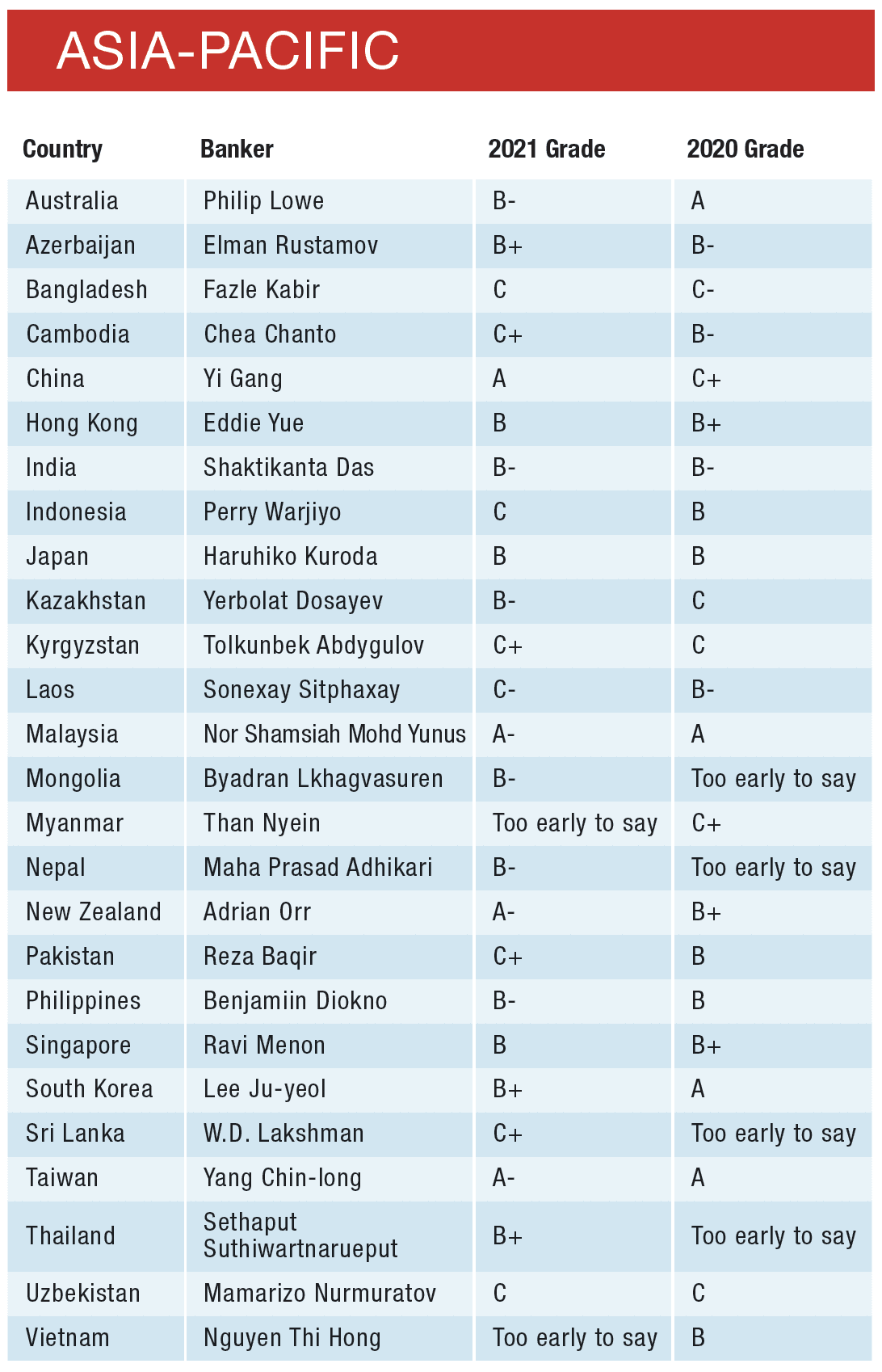

ASIA-PACIFIC

AUSTRALIA

Philip Lowe | GRADE: B–

It could be argued that in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Reserve Bank of Australia was not bold or quick enough–a frequent past refrain in criticism of the RBA.

The initial response was to cut the cash policy rate to 0.25% and to conduct a quantitative easing program on government bonds with three-year tenors, targeting an approximate 0.25% yield.

By November the RBA had realized the response was insufficient ,and that month the policy rate was cut to a record low 0.1%, while bond purchases were extended to five and 10-year tenors and included state and territory bonds, with A$100 billion to be purchased over the subsequent six months.

Perhaps the year-end response should have happened sooner, as the pandemic hit, allowing greater and quicker relief for borrowers, particularly frequent debt market issuers who would have been able to lock in cheaper term funding sooner at those longer tenors–particularly at the critical 10-year curve point–on the assumption of a rocky economic road ahead.

AZERBAIJAN

Elman Rustamov | GRADE: B+

The Central Bank of Azerbaijan perhaps has an easier job than its peers in the Caucasus given the support provided to the national currency, the manat, by the state oil fund Sofaz, whose US$43.2 billion reserves dwarf the US$6.49 billion held by the central bank.

A de facto peg to the US dollar enabled the manat to remain stable at 1.7 to the unit since 2017–it is one of the region’s most solid currencies–and this, in turn, helped hold inflation down at 2.6%, within the 2% to 4% band the bank adopted last year.

The bank utilized macro prudential easing in 2020, which allowed for a 100 bps decline in the refinancing rate to 6.5%–no radical easing here, although arguably more could have been done, given a 6.3% unemployment rate and a 4.3% GDP decline. A reserve requirement cut was not forthcoming but would have been welcome in releasing liquidity into a low-inflation economy.

BANGLADESH

Fazle Kabir | GRADE: C

GDP growth was surprisingly positive in Bangladesh last year, coming in at 2.4%, thanks to the impact of a US$12 billion Covid-19 stimulus fiscal package and structural credit support provided in the context of rising non-performing loans. Bangladesh Bank played its part, cutting the cash reserve requirement by 150 bps in March, with the liquidity support failing to spur inflation, which remained within the bank’s 5.04% to 5.93% target, at 5.7%

The term of Governor Fazle Kabir was extended last year amid a turbulent background in response to Covid-19, with parliament suspended and IMF aid required to help stem its negative effects on the balance of payments. Bangladesh Bank eased liquidity to support the financial sector. The national currency, the taka, remained stable versus the US dollar, at around 0.01 since 2018.

The bank is regarded as only around 40% independent of the government and fears of deficit monetization persist as a result.

CAMBODIA

Chea Chanto | GRADE: C+

Cambodia’s economy is heavily dollarized and largely based on cash, something which has hindered the effective implementation of monetary policy over the years.

In response to this structural impediment, the National Bank of Cambodia energetically pursued the development of the central bank digital currency (CDBC), the Bakong, in order to promote the use of local currency and digital payments within Cambodia.

The NBC has been one of the first movers in relation to CDBC in APAC, kicking off a pilot scheme over two years ago; the hope is that the digital currency will radically revolutionize the monetary backdrop in Cambodia. This effort is laudable, but it has yet to generate systemic results.

At 2.9%, inflation was relatively subdued in 2020, versus an informal 5% target, while GDP growth came in at -3.1%, a reasonable result in the context of Covid-19, but within the framework of relatively low inflation and unemployment, the NBC should have released greater liquidity via a steeper reserve-requirement cut than that introduced last March.

CHINA

Yi Gang | GRADE: A

China’s central bank relied on no quantitative easing or direct buying of government bonds to stimulate the economy after GDP slumped by 6.8% in the first quarter, its first contraction on record. The heavy lifting was done by the Finance Ministry, which issued a record amount of special-purpose bonds. The People’s Bank of China lacks the freedoms enjoyed by most central banks and doesn’t make monetary policy.

New loans are expected to reach a record $2.7 trillion this year, an increase of about 20%, as the central bank has guided financing costs lower. In February, it cut the one-year loan prime rate by 10 basis points to 4.05%. In April, it trimmed the rate by another 20 basis points. The central bank lowered its bank reserve requirements at the direction of China’s cabinet. Governor Yi Gang says the peak of easing has passed and it is time to start considering the timely withdrawal of policy tools.

HONG KONG

Eddie Yue | GRADE: B

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority responded to the economic impact of the pandemic by releasing HK$1 trillion into the city state’s monetary system to increase lending capacity. This was done via a reduction of the countercyclical capital buffer from 2% to 0.5%, a 50% cut in regulatory reserves (which released HK$200 billion of lending capacity), the deferral of Basel III requirements for financial institutions and the provision of dollars to local banks via repo transactions with the US Federal Reserve.

The central bank also set up the Banking Sector SME Lending Coordination Mechanism to help banks support small and midsized enterprises and introduced the Payment Holiday Scheme to run from May 2020 to October 2021 in which over 100 local banks participated.

Despite these measures, Hong Kong’s GDP fell 6.1% last year, with only India and the Philippines faring worse among APAC’s major economies.

INDIA

Shaktikanta Das | GRADE: B–

In May 2020 the Reserve Bank of India took the lead in the “total stimulus” package–representing 10.5% of GDP–announced by the government in response to Covid-19. As with much of APAC’s central bank sector, the RBI’s response has consisted of conventional and unconventional measures.

There was a 115 bps cut in short-term policy interest rates, and cash reserve ratio requirements were slashed by 100 bps from March through May.

It could be argued that the conventional policy options were hampered by the previous deep policy rate cut of 135 bps the previous year–which was more than that introduced by regional CB peers in their Covid response–due to a decline in India’s economy.

Unorthodox measures included LTRO, TLTRO, variable repo options, financing opportunities for non-bank FIs and advances to the government–a potentially worrying trend toward monetization of the budget deficit.

The RBI initiated yield curve control last year in the form of “Operation Twist” by selling short-term bonds and buying longer tenors. Despite the relative success of this maneuver, Indian inflation remained stubbornly high at 6.6% and growth plummeted by 8%.

INDONESIA

Perry Warjiyo | GRADE: C

A case can be made that Bank Indonesia could have done more in its pandemic response but that it was constrained by the vulnerability of the rupiah, which touched an 18% depreciation at its lowest point versus the dollar in 2020, subsequently recovering ground but still off 5.7% for the year.

Within that constraint, the bank cut the policy rate by 100bp in the first quarter as well as trimming reserve requirements by 200bp for conventional banks and 50bp for Islamic banks.

Subsequent unconventional measures were undertaken including the provision that Bank Indonesia could purchase securities from the government, both in the primary and secondary market “in perpu,” with the totality of its monetary operations in 2020 totaling 4.2% of GDP.

One of the biggest market concerns in 2020 was of the bank losing its independence in the wake of its agreement on “burden sharing” with the government for deficit financing. In addition, Bank Indonesia agreed to buy almost 400 million Indonesian rupiah of government securities to help fund relief measures.

JAPAN

Haruhiko Kuroda | GRADE: B

For the Bank of Japan, 2020 represented a continuation of the ongoing QE program which has been in place since 2013, only with a sharp eye on containing borrowing costs in the face of severe Covid-19-induced growth pressure.

Versus the pre-pandemic language of pledging to buy 80 trillion yen of Japanese government bonds (JGBs) a year, the BoJ upped this to an “unlimited quantity.” Policy rates remained at -0.1% while the 10-year JGB was still targeted in the bank’s yield curve control policy, at 0% YTM.

In response to the pandemic the BoJ bought equities, commercial paper, corporate debt, ETFs and J-REITs, leaving it open to the charge of bloating its balance sheet to unsustainable levels, wherein QE efforts equated last year to some 116% of GDP and the bank owned around 40% of the JGB market.

The BoJ’s failure to generate meaningful inflation since the introduction of “Abenomics” in 2012 must return a “could do better” assessment for Governor Kuroda, despite some success in liquidity easing and containing yen appreciation last year and the market-supporting clarity of forward guidance.

KAZAKHSTAN

Erbolat Dossaev | GRADE: B–

The National Bank of Kazakhstan faced a stern test in early 2020 as the tenge depreciated by 15%. Given the country’s vulnerability to imported inflation, the bank responded decisively by increasing the policy rate from 9.25% to 12% in a successful bid to stabilize the currency, aided by a current account surplus.

In the process, the NBK avoided runaway inflation, albeit outside the bank’s 4%-6% target range, with CPI coming it at 6.7% for the year.

In the face of pandemic-induced downside growth pressure, the rate was cut to 9%, although much of the country’s Covid-19 response was handled via fiscal and macro prudential policy. In June of 2020 the NBK was split into core banking and regulatory functions, which will enhance the institution’s independence going forward.

KYRGYZSTAN

Tolkunbek Abdygulov | GRADE: C+

The National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic produced something of a lackluster performance in 2020, increasing the policy rate from 4.25% to 5% last February, leaving the reserve ratio requirement unchanged and relying on direct liquidity injections to banks together with loan payment deferrals as its core Covid-19 response.

The basic economic data do not make pretty reading: unemployment was up at 7.9% while GDP came in at -8.6% for the worst performance in APAC outside Myanmar.

Admittedly, the NBKR’s hands were somewhat tied by the 19% fall in the sim as the pandemic broke, and to the bank’s credit it managed to contain inflation–which clocked 6.3% in 2020–within its 5%-7% target range.

LAOS

Sonexay Sitphaxay | GRADE: C–

GDP growth of 0.4% was the lowest for three decades in Laos last year and the country retained its least-developed nation status, with the 65% public external debt load to GDP–versus 59% in 2019–a sword of Damocles hanging over the country in the form of potential distress.

The Bank of the Lao PDR is not independent and is controlled by the Politburo. Inflation and its causal link to the level of the kip–which is overseen on a managed floating exchange rate basis–has been the predominant policy concern, particularly given the hyperinflation Laos experienced in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis, when it hit 110%.

Given the depreciation of the kip last year thanks to pressure on the balance of payments due to strong demand for the dollar and Thai baht for trade settlement–where a parallel market exists at much lower rates than the official one–inflationary pressure built up, coming in at 5.1%.

MALAYSIA

Nor Shamsiah Mohd Yunus | GRADE: A–

Bank Negara Malaysia retained its status in 2020 as one of Asia’s most savvy central banks, and although there remains concern about the monetizing of the fiscal deficit, the independence of BNM enshrined in the Central Bank of Malaysia Act is in no doubt.

The bank engaged in limited QE last year, capping its purchase of Malaysian Government Securities at 10% of individual issues in order to maintain secondary market liquidity. This effort to contain borrowing costs was combined with a 100 bps cut in the Statutory Reserve Requirement to 2% and a 125 bps easing of the overnight policy rate.

Wiggle room was provided in the form of a 9% appreciation of the ringgit versus the dollar, and the bank soundly met its inflation mandate by sitting on a moderation of the core rate to 0.8% from 1.4%.

MONGOLIA

Byadran Lkhagvasuren | GRADE: B–

Much like many of its regional central bank peers, BNM is studying the possible implementation of a digital CB digital currency but has voiced fears over the possible cannibalization of commercial banks via a CBDC competing with deposits. Mongolbank’s primary aim is to keep a lid on inflation–it has a 4% to 8% target which it undershot by 0.3% last year, with inflationary pressure contained by a strong tugrik amid positive sentiment buoyed by Mongolia’s surging foreign exchange reserves, which hit a record US$4.8 billion high in 2020.

Thanks to the luxury provided by a stable currency, the central bank was able to slash policy rates four times last year, by an aggressive 500 bps, providing further growth support via the extension of a consumer loan moratorium.

The bank is not fully independent, and if there is a fiscal policy shortfall it can be called upon to finance the budget deficit. A looming issue for the bank is the overhang of “policy loans” made to finance strategically important assets such as those within the mining sector and of which many are in default.

MYANMAR

Than Nyein | GRADE: Too early to say

Myanmar suffered a 10% drop in GDP last year, for the worst performance within APAC, a shocking number given that prior to the onslaught of Covid-19 the World Bank slated the country to grow by 6.4%, driven by its strong service, industrial and agricultural sectors.

The Central Bank of Myanmar cut the policy rate by 2% in 2020, capped the maximum secured lending rate at 11.5% and cut the reserve requirement by 200 bps as part of its Covid-19 response. Despite the fraught economic backdrop, exacerbated by ongoing conflict in the north of the country, the kyat was Asia’s best-performing currency last year, gaining 11% versus the dollar.

NEPAL

Maha Prasad Adhikari | GRADE: B–

Nepal Rastra Bank responded nimbly to the economic effects of the pandemic, with the 5% increase in the credit to core capital ratio a key move to boost liquidity as well as a 100 bps cut in the compulsory cash reserve ratio.

And some 300 billion Nepalese rupee was released into the financial system via reductions in repo rates while banks had extra capital to play with via a suspension of the requirement to set aside funds as countercyclical buffers.

A point of criticism for NRB is its tolerance of funds which might have been earmarked for SMEs being channeled through “big ticket” loans–in amounts over Rs10 million–to large corporations at concessional rates of 5% in what is best described as directed lending and with these loans accounting for around 45% of all loans in the Nepalese system.

This provides an uncertain backdrop of credit concentration risk as well crimping bank profitability and presenting immense risk to the country’s financial system.

NEW ZEALAND

Adrian Orr | GRADE: A–

At the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Governor Adrian Orr has been blunt in his willingness to apply negative interest rates should they be required to boost New Zealand’s low-inflation economy.

That striking pose notwithstanding, the bank ticked most of the boxes last year in its Covid-19 response, initiating QE with a NZ$100 billion purchase target of government and local government bonds, with the program set to last until 2022, having completed NZ$44.2 billion of large-scale asset purchases by January 2021.

The official cash reserve rate was cut by 25 bps to 0.25% and plans to hike banks’ capital requirements were delayed until November 2021.

Last December the RBNZ unveiled its “funding for lending” program with the aim of reducing banks’ funding costs, and had communicated in strong terms in 2020 to the market that policy interest rates would not rise until 2021.

PAKISTAN

Reza Baqir | GRADE: C+

The response of the State Bank of Pakistan to Covid-19 was surprising, to say the least, with the policy rate left unchanged at 7% during 2020, presenting one of the most jarring negative real rate outcomes in Asia, given the country’s 8.6% inflation rate. With inflation having receded from 11.1% in 2019, it might have been hoped that bolder action was called for regarding policy rates.

In a scant measure of liquidity support, the central bank cut the special cash reserve requirement for foreign currency deposits by 500 bps to 10%, instructed commercial banks to suspend dividend payments and cut the margin requirement from 30% to 10%. But there is a sense that more could have been done.

Still, it’s worth remembering that Pakistan only emerged from full-blown financial crisis prior to March 2020 and was under the auspices of the IMF, which had urged fiscal consolidation in the country.

PHILIPPINES

Benjamin Diokno | GRADE: B–

The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas in the Philippines last year conducted a QE campaign–described in the financial media as “QE Lite”–which may be characterized as tinged with waywardness, given its mechanism of buying up government securities minus volume limits or target tenors. This program eventuated in the BSP owning 20% of the Philippines’ government bond market for a bill of Ps1.1trn last year.

Conventional monetary policy was conducted alongside the unorthodox variety, with 175 bps of policy rate cuts initiated in 2020 plus a 200 bps cut of the reserve ratio requirement which injected Ps1.3 trillion of liquidity into the system.

Again, as with the other central banks discussed above, a concern for the BSP is the pressure it is under from central government to help finance the fiscal deficit via short-term advances–to date of a three-month tenor. Even though this borrowing is capped at Ps810 billion the, sensation is of a drift toward full-on deficit financing.

SINGAPORE

Ravi Menon | GRADE: B

The Monetary Authority of Singapore stared down the risk of disinflation becoming deflation in 2020 as its trade-dependent economy faced the headwinds of slumping global demand, even though the country has experienced a heady rise in money supply, with M1 surging by around 21% every month between March and August, mainly thanks to a spike in demand deposits.

Core inflation was -0.2%, exacerbated by an appreciation of the Singapore dollar versus the US dollar and yen, and the central bank’s 2% reduction of its policy band helped steer market-based interest rates to all-time lows, with three-month SIBOR and the Singapore dollar swap offer rate dropping to 0.4% and 0.2%, respectively.

Credit support was provided by MAS in October to individuals and SMEs hit by the Covid-19-induced downturn, although much of the country’s pandemic response was executed via fiscal policy.

MAS earned its ESG chops last year by establishing a Singapore dollar facility for ESG loans.

SOUTH KOREA

Lee Ju-yeol | GRADE: B+

Bank of Korea engaged in “Korean-style QE” last year, providing unlimited liquidity support via three-month repos, with the program coming alongside a 75 bps policy rate easing to 0.5%.

The bank has faced criticism for the lukewarm nature of its venture into unorthodox monetary policy, which was short-lived; QE was ditched in July after being judged to have provided sufficient market liquidity–KRW19trn–and even though BoK governor Lee Ju-Yeol floated the idea that the scheme could include corporate bond or commercial paper purchases this did not happen. The scheme may yet reappear, however.

The truth about the BoK’s experiment is that it didn’t so much represent standard QE which is effectively about central banks printing money but in Korea’s case looked more like conventional liquidity management, even though the bank showed initiative in extending the scheme to a wider range of institutions than would normally be included and spread the net wider in terms of securities eligible for inclusion in the scheme.

SRI LANKA

W.D. Lakshman | GRADE: C+

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka reduced the standing deposit and standing lending facilities in 2020, to historic lows of 4.5% and 5.5%, whilst the statutory reserve ratio was also reduced to a record low.

The country faced inflationary pressure last year, with the core rate coming in a 6.2%, above the top end of the central bank’s 4%-6% target. A 2% depreciation of the rupee versus the US dollar added to inflationary pressure as did the expansion of private credit.

Again, there is a creeping dynamic towards monetization of Sri Lanka’s budget deficit via central bank credit to the government, which expanded by a hefty 74% last year, calling into question the bank’s independence, something only exacerbated by the shelving in 2019 of a law designed to recraft its management into three boards rather than the current single board.

TAIWAN

Yang Chin-long | GRADE: A–

Perhaps no other central bank in APAC enjoys the prestige and full autonomy as that bestowed on the Bank of Taiwan, and it would be fair to say that the institution has earned its privilege.

The bank’s job has been made easier in recent years in the form of surging exports–thanks in part to former US President Trump’s trade war with China–and hence a healthy current account surplus.

Bank of Taiwan reduced the discount rate to a record low of 1.125% last year, keeping the refinancing rate on secured loans steady at 1.5% and providing SME support via US$6.6bn of special loans.

This policy proved on the mark as Taiwan’s GDP returned to pre-pandemic levels in the third quarter of last year, with unemployment manageable at 3.8% although at -0.2% inflation was perhaps too low. The bank forecasts inflation but does not target it and governor Yang Chin-long has disavowed the possibility of negative interest rates.

THAILAND

Sethaput Suthiwartnarueput | GRADE: B+

The Bank of Thailand’s governor Sethaput Suthiwarnarueput last October compared the country to a “patient in an intensive care unit” an appropriate comment given the damage the pandemic has wreaked on the Thai economy’s key tourism industry – crimping 10% from GDP last year – to say nothing of the political unrest backdrop and declining exports which collapsed 18% in 2020.

Still, the economy managed to avoid the BoT’s forecast of a 7.8% drop in GDP last year, printing a 6.1% decline. Support was provided in the form of a debt moratorium initiated in April 2020 which was extended to June of this year and was focused on SMEs. The bank has voiced concern that the moratorium could create moral hazard and systemic risk to the financial system.

There were three policy rate cuts in 2020, bringing the rate to an all-time 0.5% low and banks were allowed by the BoT to use investment grade bonds as collateral to borrow within its US$30bn lending facility.

UZBEKISTAN

Mamarizo Nurmuratov | GRADE: C

Last year was not an easy one for the Central Bank of Uzbekistan as inflation was rampant, clocking 12.9% thanks to a decline in the sum–in the face of collapsing exports to China and Russia and declining raw materials prices–and the effects of a 10bb cut in the policy rate to 15%.

The country appears to have concluded that a fully independent central bank would enhance its economic prospects and in 2019 overhauled the central bank law to that effect, under which inflation targeting was introduced in 2020–at no more than 10% in 2021 and 5% from 2023 onwards–and wherein the policy rate must be reviewed eight times per year.

VIETNAM

Nguyen Thi Hong | GRADE: Too Early to Say

Last year the State Bank of Vietnam successfully kept a lid on inflation–which came in at 3.85% against the backdrop of a stable dong, helping to deliver one of the few convincing GDP growth stories in APAC, with growth registering a relatively impressive 2.9% year-over-year.

Vietnam was less affected by the impact of Covid-19 than many of its regional peers, having sealed borders early and conducting an early, although brief lockdown.

Although the reserve ratio was not cut, liquidity was provided via the imposition of low return rates on dong and foreign reserves of 0% and 5% respectively, providing banks with an incentive to lend.

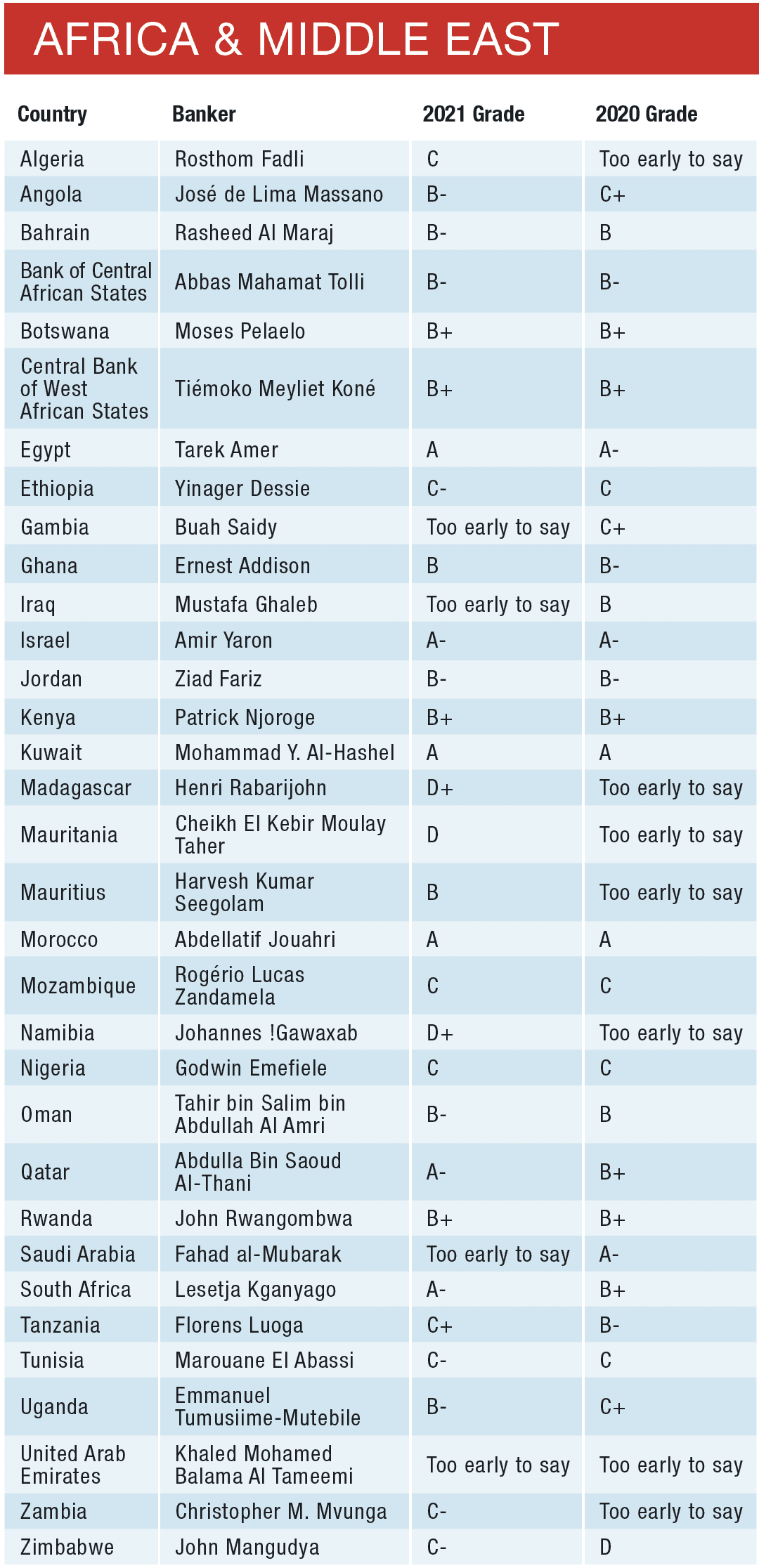

Middle East & Africa

ALGERIA

Rosthom Fadli | GRADE: C

In 2021 Algeria started a fragile recovery, mainly on the back of higher hydrocarbon prices and public spending, but the slow pace of vaccination (less than 20% of the population is expected to be vaccinated by the end of the year) is still a major obstacle. Governor Rosthom Fadli prolonged the policy rate cuts implemented at the beginning of the pandemic and gradually lowered reserve requirements from 10% to 2% in February 2021, but the additional liquidities were quickly converted into currency in circulation and banking deposits further declined. Credit-wise, Fadli lowered the liquidity coefficient to 60% but credit growth slowed down significantly and the majority of credit lines that were issued profited state-owned companies rather than SMEs or households. Inflation was contained to 2,8% in 2020 but expected to be higher in 2021 and the real economy is still dependent on black market exchange rates. Despite repeated calls from international institutions to boost private sector the Algerian economy remains dominated by state-owned enterprises.

ANGOLA

José de Lima Massano| GRADE: B–

José de Lima Massano demonstrated unbridled zeal in pushing for the independence of the National Bank of Angola (NBA). This year he made a breakthrough with the enactment of a new law, which among other things gave NBA a new mandate to stabilize prices. NBA monetary policy committee took the new mandate with gusto, increasing its benchmark rate by an unprecedented 450 basis points, to 20% from 15.5% in July. With the rate last raised in November 2017, NBA was explicit the huge adjustment is designed to tame inflation. In June, inflation rate stood at 25.3%, up from 24.9% in May. This has made the central bank resort to aggressive measures to attain its target of 19.5% by year end. Apart from reigning in on inflation, Massano is also spearheading the clean-up of banks, particularly state-owned and he’s pushing for recapitalization after setting the minimum core capital at $11.6 million.

BAHRAIN

Rasheed Al Maraj | GRADE: B–

Tiny Bahrain is trying to keep its head out of the water after the dual shock from the pandemic and falling oil prices. Throughout 2021, the government and the CBB chose to extended the COVID stimulus package – including loan instalments to help households, banks and businesses get back on track. Growth is expected to reach 3,3% this year but it proving increasingly costly for Bahrain to keep on spending without serious fiscal reform. Debt to GDP ratio increased exponentially, from 102% in 2019 to 133% in 2020. The IMF expects it to reach 155% in 2026. Bahraini banks remained sound and strong throughout the crisis, although the IMF warns there might be concerns over profitability and asset quality once the effects of stimulus packages wear off. Governor Rasheed Al-Maraj is particularly forward-thinking when it comes to Fintech, cryptocurrencies, cloud and innovation in general.

BANK OF CENTRAL AFRICAN STATES (BEAC)

Abbas Mahamat Tolli | GRADE: B–

BEAC is agile in balancing the economic interests of its six member countries namely Gabon, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Republic of the Congo and Equatorial Guinea CEMAC. Amidst the ravages of Covid-19 that saw the region plunge into a severe recession in 2020, BEAC has maintained its benchmark rate at 3.25% since March to stimulate economic recovery. BEAC has admitted the road to recovery is bound to be bumpy and has downgraded its economic growth projections to 1.3% this year from 1.9% forecast in April. Part of measures to stimulate recovery have included weekly liquidity injection operations to support the CEMAC banking system and boost financing of key sectors of the economy. With the pandemic’s impacts on CEMAC economies easing, BEAC has resumed liquidity absorption operations to mop-up excess liquidity. Early September, it launched an operation aimed at absorbing $180.2 million from banking system. This followed a similar operation in late August.

BOTSWANA

Moses Pelaelo | GRADE: B+

Botswana’s central bank cut its benchmark interest rate to a record low of 3.75% from 4.25% in October last year. Since then, the rate remained unchanged to support economic growth and contain inflation, which at 8.9% in July remained above the upper bound of the bank’s medium-term target range of 3%-6%. In its August meeting, the bank’s monetary policy committee signaled its intent to remain accommodative. Botswana, whose economy contracted by 8.9% in 2020, is set for an astonishing rebound. Government projects 9.7% growth in 2021, compared with 8.8% forecast in February due to higher diamond sales and a recent rebasing of GDP accounts. Despite boasting of a vibrant banking sector, Pelaelo wants BOB to have more autonomy and is pushing for amendment of laws in that direction, which should facilitate innovation.

CENTRAL BANK OF WEST AFRICAN STATES (BCEAU)

Tiémoko Meyliet Kone | GRADE: B+

Political instability in West Africa, including two coups in Mali, a member of BCEAO, is raising concerns over immediate and short-term economic prospects of the region. BCEAO monetary policy committee, in its June meeting, reckoned that improving of the security situation is a prerequisite in sustaining recovery that is projected at 5.6% in 2021 from 1.5% last year. The bank, which besides Mali also serves Senegal, Togo, Burkina Faso, Benin, Niger and Côte d’Ivoire, has adopted an accommodative monetary stance. The bank has maintained its benchmark rate at 2% since June last year. This is driven by favourable macroeconomic factors including inflation that stood at 2.2% in the first quarter. Over the next 24 months, BCEAO forecasts the rate to stand at 1.9%, which should be within its target zone of 1-3%. For Koné, having his contract renewed in August last year for another 6-year term is a show of confidence in his leadership.

EGYPT

Tarek Amer | GRADE: A

Governor Tarek Amar continues on his mission to reform the Egyptian economy. Late 2020, the CBE passed a new banking law to strengthen the financial sector. Key changes include an important increase in minimum capital requirements for local and foreign banks, new ownership regulations and compulsory publication of financial data. Law 194/2020 also gives provisions for the CBE to issue digital banking licenses, although this has yet to be implemented. Egypt’s fintech sector is currently booming partly thanks to the CBE’s forward-thinking approach to innovation. In 2021, inflation grew above 5% but remains within official targets. Amar’s data-driven monetary policies were praised by international financial institutions and investors. In 2020, Egypt was one of the only countries in the world to escape recession and this year 5,2% growth is expected.

ETHIOPIA

Yinager Dessie | GRADE: C–

Since 2018 when Abiy Ahmed took office as Ethiopia’s prime minister, the country has been on a reform trajectory. Part of the reforms have included gradual and partial opening of the financial services sector. After years of stellar economic performance, growth is projected at a mere 2% in 2021. A domestic crisis has stalled economic policies, including plans by the National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) to set up a benchmark interest rate and introduce a floating exchange rate. Ethiopia is already grappling with dwindling foreign exchange reserves, which stood at $3 billion in 2020. This has forced NBE to embark on a gold buying spree to shore up reserves.

THE GAMBIA

Buah Saidy | GRADE: Too Early to Say

The Gambia is under intense pressure, with a third wave of Covid hampering recovery, according to the IMF’s September review. The central bank under Saidy remains accommodative so far.

GHANA

Ernest Addison | GRADE: B–

The Bank of Ghana is proving its mettle in steering monetary policy. For most of the year, the bank followed a tight monetary stance. It held its policy rate at 13.5% following a 100 basis points cut in May. The tight stance resulted in headline inflation declining from 10.3% in March to 7.8% in June. The Cedi remains largely stable while the country has managed to boast reserves following the issuance of a $3 billion Eurobond in March. Flipside is that a huge chunk of the proceeds will be directed towards public debt servicing. Stock of public debt stands at $5.5 billion, equivalent to 76.6% of GDP. After structural reforms of the banking sector, the industry is on a sound footing underpinned by improved solvency, liquidity and profitability.

IRAQ

Mustapha Ghaleb | GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Governor Mustafa Ghaleb was appointed in September 2020 – he faces the difficult task of overseeing the stability of the Iraqi banking sector when the country is struggling with war, debt, international sanctions and traffics.IT is too early for Global Finance to evaluate his performance.

ISRAEL

Amir Yaron | GRADE: A–

Israel’s central bank has been aggressive in its 2020 actions to preserve macroeconomic and financial stability. As a result, the economy experienced a milder contraction than other developed countries (GDP was down 2.6% and it is expected to increase by more than 5% in 2021). The central bank, which has a solid reputation, is expected to wind down some of its current expansionary tools if a fourth coronavirus lockdown is not proving too negative on the economy.

“Alongside the anchoring of interest rates at close to zero, the central bank’s policy framework has enabled the smooth financing of the economy and a strong rebound in economic activity. Israel’s economy bounced back following its rapid vaccination rollout earlier this year and the central bank started to phase out some of its emergency support programs. The initiative that provided discounted loans to the banking sector ceased in July and the central bank will probably stop its bond purchase program at the end of this year,” says Liam Peach at Capital Economics.

“Intervention in the FX market will remain a key part of the central bank’s toolkit for some time, but the size of these purchases may fall as the global recovery matures and sharp upwards pressure on the shekel subsides. Even so, Israel’s economy is likely to struggle to generate the price pressures needed to meet the central bank’s 1-3% inflation target on a sustained basis and the prospect of interest rate hikes will remain a distant prospect,” says Peach.

JORDAN

Ziad Fariz | GRADE: B–

To save itself from the pandemic, Jordan borrowed on international capital markets as well as from bilateral and multilateral sources. As a result of these financial inflows, the CBJ increased its reserves – that now cover three times the required benchmark. This shows resilience to external shocks but public debt is soaring at almost 100% of GDP. In 2020, Governor Ziad Fariz reduced required reserve ratio from 7% to 5% providing banks with $775 million free of charge to help them support credit growth and investment. Credit to private sector grew by 6,3% in 2020 compared to 4,3% in 2019 and early data from 2021 shows demand for credit remains strong. Being an oil importer, Jordan benefited from the drop in energy prices during the pandemic. The economy contracted by only 1,6% but the labour market was hit hard with unemployment rising to 24,7%. This year, economic recovery is expected to be very mild.

KENYA

Patrick Njoroge | GRADE: B+

Rising political temperatures as Kenya heads into an already bitterly divisive presidential transitional election in August next year is igniting economic consternations. Going by history, Kenya is prone to violence during elections. The central bank reckons the rising temperatures do not augur well for the economy that is on recovery trajectory after being ravaged by Covid-19. With the economy operating below its potential level, the apex bank has stuck with an accommodative monetary policy stance. Effectively, the benchmark rate has remained unchanged at 7% since March last year. In July, the bank published a white paper that it contends will enhance the effectiveness of monetary policy and support anchoring of inflation expectations. The objective is a shift towards forward-looking policy approach. Despite being open-minded on financial innovations, Njoroge has banned currency speculative trading and presided over local currency stability with an iron fist.

KUWAIT

Mohammad Yousef Al-Hashel | GRADE: A

Governor Mohammad Al-Hasheel is one of the main advocates of economic reform in Kuwait. In a country where public wages account for half of the state budget, recent actions include lowering the risk for SMEs from 75% to 25% and changing the bankruptcy law to free business owners from the threat of imprisonment in case of debt defaults. The CBK is also very pro-active on fintech and digital banking. This year, inflation was under control and the Kuwaiti dinar remained stable but the country still faced many challenges such as the inability to issue debt for lack of a debt law. “Monetary tools are not sufficient to address structural challenges” Al-Hashel said during a conference in July. “There is an urgent need for economic reforms, and all parties, especially the executive and legislative authority, must work to address all imbalances”. For the foreseeable future, oil exports will continue to drive Kuwait’s economy. After declining by 9,9% in 2020, the country’s GDP should grow 2.4% in 2021.

LEBANON

Riad Salamé | GRADE: B–

Riad Salameh has served as governor of Banque du Liban for 27 years, maintaining monetary stability through a long series of crises and winning a string of A grades from Global Finance. His record has been stained, however, by recent allegations that he inflated the bank’s assets by more than $6 billion using unorthodox accounting methods. Salame says the central bank’s accounting systems “are not hidden from anyone” and are used by other central banks.

He has been feuding with the former prime minister of Lebanon, Hassan Diab, whose government defaulted on $90 billion of debt in March—over Salameh’s objections. The Hezbollah-led government resigned after the deadly August 4 explosion in Beirut triggered public outrage. Salameh has a court date this month, after a group of Lebanese lawyers formally accused him in July of embezzlement of central bank assets and mismanagement of public funds. Salameh has described the lawsuit as “groundless.”

MADAGASCAR

Henri Rabarijohn | GRADE: D+

Madagascar’s financial services sector, according to the IMF, is in dire need of widespread structural reforms. These cuts across strengthening of the monetary policy framework to transition to interest targeting, increasing the efficiency of the foreign exchange market, strengthening financial sector stability and development to pursuing financial inclusion. Despite being in office for close to two years, Rabarijohn, who became governor in November 2019, has performed dismally on all fronts. The consensus is that Rabarijohn is yet to stamp his authority in steering the country’s central bank, which in August held its policy rate at 7.20%. When the IMF approved a $312.4 million loan under the Extended Credit Facility in March, it put the apex bank on the spot over its forex management program centered on increasing gold reserves. The banking sector also remains underdeveloped, with four banks commanding over 80% market share in a country where only 30% of the adult population has a bank account.

MAURITANIA

Cheikh El Kebir Moulay Taher | GRADE: D