After years of easy money, central banks are tightening up—some more quickly than others. Global Finance grades their performance in the face of the past year’s rising inflation.

Although not every central bank has the same mandate, in many countries, the central banker’s primary job is to know just when, which way and how far to change interest rates to maintain price stability. As inflation took hold over the past year those were, at the very least, the central questions.

While macro impacts are notoriously slow to be felt, with today’s hindsight, it seems central bankers in some of the world’s biggest economies may have punted a little too far, while those in emerging market economies reacted more quickly.

“Due to their different historical experiences, it would be expected that central banks in advanced economies and emerging market economies would have distinct reactions to the current inflationary episode,” argues Roberto Campos Neto, governor of Banco do Brasil. “Central bankers in advanced economies, after several years fighting against low inflation, would be generally more tolerant with higher inflation. Conversely, central bankers in EMEs, with their history of higher inflation, would be more reactive in monetary policy tightening.”

Brazil, Chile, Peru, Uruguay and the Dominican Republic were among those that pivoted to tightening in 2021. “Emerging markets in general and Latin America in particular can offer some ideas to central banks in advanced economies on how to deal with inflation,” says Marcelo Carvalho, head of Global Emerging Markets Research at BNP Parias in London. “Latin America, and emerging markets in general, are quite used to inflation.”

Also, as observers note, advanced economies get more leeway from the market. “The Fed can be slow to react to an inflation problem without suffering a capital flight from the United States,” says Ethan Harris, head of Global Economics Research at Bank of America Securities. “Whereas if you’re a small, developing economy, you have to keep one eye on capital flows.”

Beyond Inflation

More than inflation preys upon the minds of central bankers. FX rates, reserves and the health of the banking sector fall within their purview, too, all part of their ultimate mandate: to maintain a systemwide stability that enables the economy to deliver for society as a whole.

Recent shocks, along with the increasingly clear impacts of climate change, are undermining long-held notions, however. “The globalization process that served the world’s economies and its people’s welfare so well in recent decades now seems to be facing significant challenges,” says Amir Yaron, governor of the Bank of Israel. “Global growth will suffer if these issues are not resolved.”

And now, more than ever, that cannot be achieved country by country. “Policy coordination is key to overcoming the current economic challenges,” says Governor Mario Centeno of the Bank of Portugal. Yaron similarly calls for faster and more comprehensive coordination on global warming, technology flows, international taxation and health issues. “In rapidly changing times like these,” he adds, “the speed of the response is very important.” — The Editors

Methodology

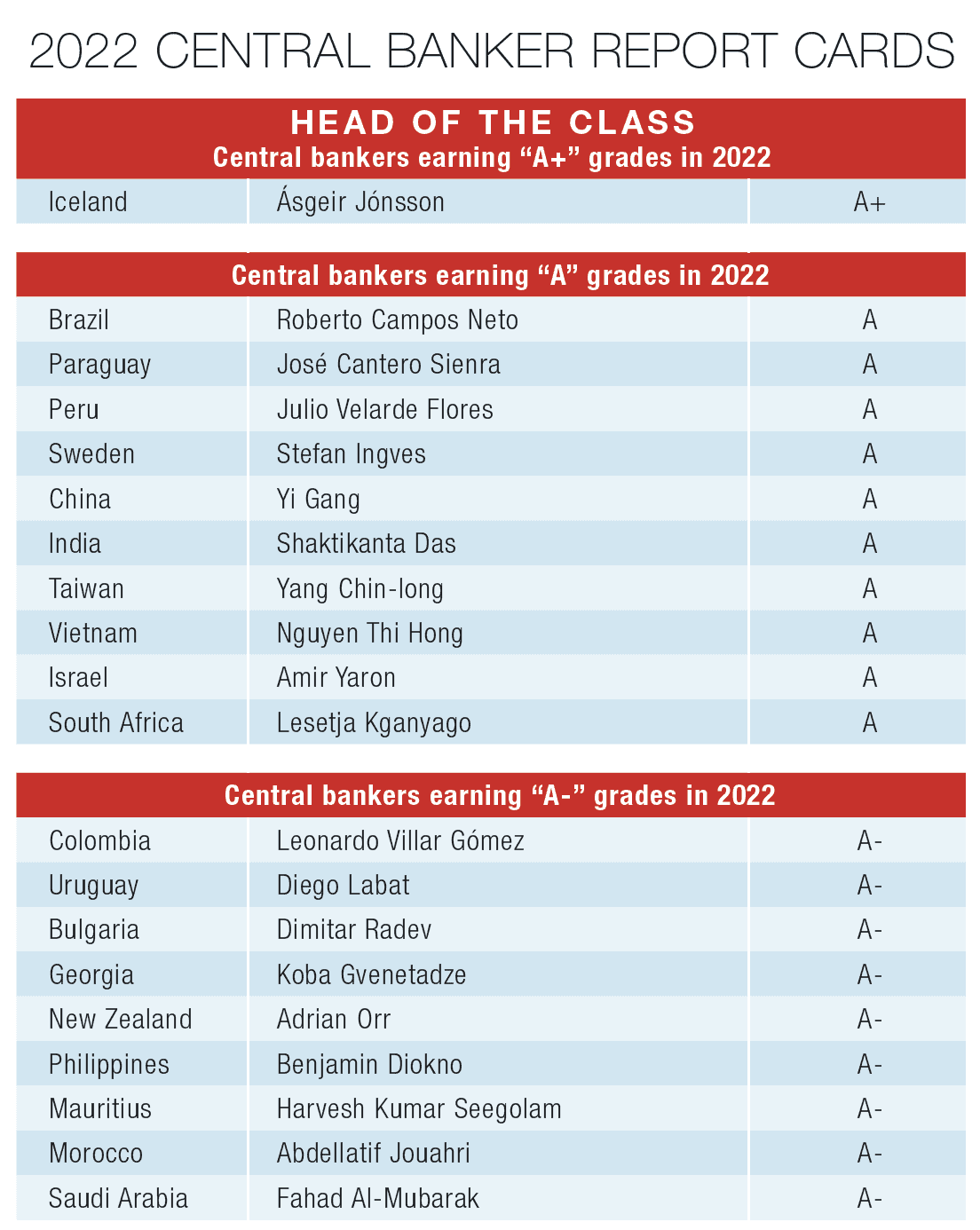

Global Finance editors, with input from analysts, economists and financial industry sources, grade the world’s leading central bankers on a scale of A to F, with A being the highest grade and F the lowest, based on a series of objective and subjective metrics, including the appropriate implementation of monetary policy for the economic conditions of each country. Judgments are based on performance from July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022. A governor must have held office for at least one year in order to receive a letter grade.

We apply an algorithm to increase the cohesion of the grades between the different geographical areas, with a score of 100 signifying perfection. The proprietary algorithm includes criteria such as monetary policy, supervision of banks and the financial system, asset purchase and bond sale programs, accuracy of forecasts, quality of guidance, transparency, independence from political influence, success in meeting specific mandates (which differ from country to country), and reputation at home and internationally—weighted for relative importance.

PROFILES BY REGION

The Americas | Europe | Asia-Pacific | Middle East & Africa

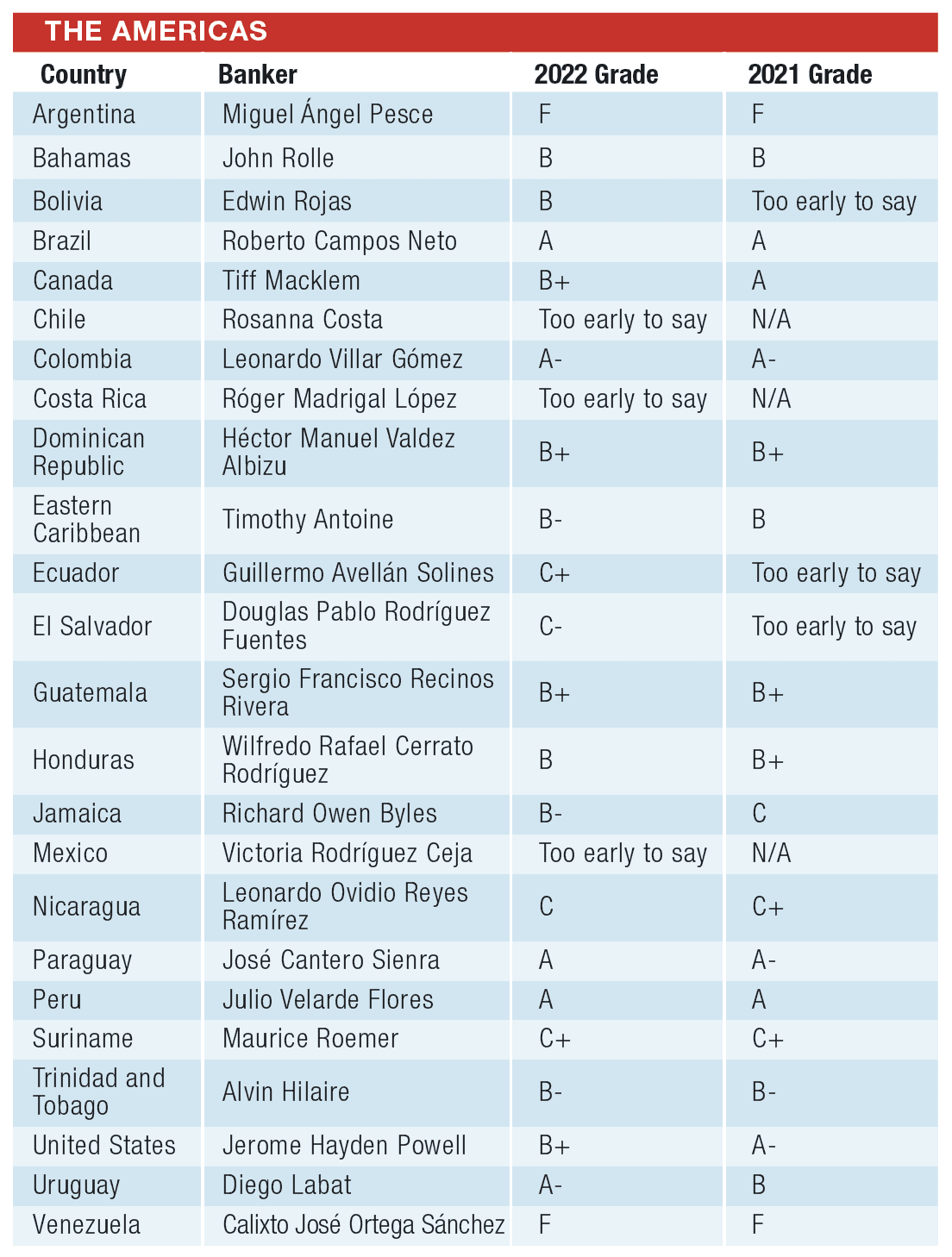

THE AMERICAS

ARGENTINA

Miguel Ángel Pesce | GRADE: F

The Argentine economy has been growing relatively well lately but suffers from increasing inflation, which, according to Moody’s Investors Service, will hit 80% in 2022. The central bank has increased interest rates, but not fast enough. The year has seen strong devaluation of the peso and highly volatile return on investment in both real and financial assets. While most of its economic problems come from fiscal policy, accommodative monetary policy has contributed. But the central bank is caught in a bit of a bind.

“Argentina needs a weaker currency to boost exports and generate the current account surpluses needed to repay external debts and rebuild foreign exchange reserves. The problem here, though, is that, with the lion’s share of Argentina’s sovereign debt denominated in foreign currency, a fall in the peso would … make it much more costly for the government to service its debts,” Capital Economics analysts wrote in an August update. “The upshot is that the likelihood of another sovereign debt crisis before the end of this decade is high.”

BAHAMAS

John Rolle | GRADE: B

The Bahamian dollar remains pegged to the US dollar on a one-to-one basis, limiting the central bank’s options. The economy was improving as tourism returned, but inflation has been on the rise, sending consumer prices up 3.4%, largely due to oil and other imports, according to the central bank. The bank also boasts an improvement in external reserves, up 23% on a mix of foreign currency inflows from real estate sector activity and government borrowings. The central bank continued the introduction of its digital currency (the “sand dollar”), strengthening the payment system by reducing the need to transport currency among the 700 isles of the archipelago. The ability to make payments using mobile phones is particularly important in case of natural disasters. “The Bahamas is vulnerable to hurricanes … [and] this exposure can manifest itself through higher growth volatility,” Moody’s analysts wrote in March. “However, high income levels and the quality of infrastructure have allowed the country to better absorb climate-related shocks than the other islands in the Caribbean.”

BOLIVIA

Roger Edwin Rojas Ulo | GRADE: B

For the last 12 months the Banco Central de Bolivia (BCB) supported economic expansion primarily through its peg of the boliviano (BOB) to the US dollar. The BCB has continued to hold the peg at BOB 6.9, to reduce the pass-through inflationary pressures from imported goods, particularly oil imports, the trade for which is usually conducted in dollars, says Andrew Trahan, head of Latin America Country Risk at Fitch Solutions. The defense of the exchange rate has lowered reserves, which in February 2022 reached the lowest level in a decade. Sustainability of the exchange rate depends on the evolution of export prices, especially natural gas.

The BCB is forecasting inflation at a modest 3.3% and GDP growth of a solid 5.1% for 2022. Trahan projects 3.8% in growth: “While high commodity prices have allowed for increased social spending, we expect a slowdown once prices come down, as proceeds from international sales and exports of natural gas and gold decline.”

BRAZIL

Roberto Campos Neto | GRADE: A

The Banco Central do Brasil led in responding to nascent inflation, with multiple rate increases starting in March 2021. “The [central bank] has implemented one of the most aggressive rate-hiking cycles among global emerging markets,” says Trahan. So far, however, these efforts have not made a dent in inflation. Service sector businesses reported considerable pressure from energy, food, fuel and staff costs, according to Pollyanna De Lima, economics associate director at S&P Global Market Intelligence. “Several businesses felt the need to transfer escalating costs to clients in June,” she noted in a comment on a July S&P news release, “with the rate of change inflation reaching a fresh series peak.” While inflation is still well above target, the aggressive rate increases are expected bring it down in the second half of 2022 and in 2023. Still, “Based on the advanced stage of the tightening cycle, Brazil is one of the few countries in which financial markets are pricing in interest rate cuts next year, rather than increases,” says BCB Governor Roberto Campos Neto. “The latest inflation readings show that inflation may have peaked in 2022, mostly due to government measures to reduce energy prices.”

CANADA

Tiff Macklem | GRADE: B+

Governor Tiff Macklem, who took over the role of governor in June 2020, was slow in responding to the inflationary pressures that emerged in 2021 and 2022. Inflation may have peaked in 2022 at 8.1% in June, a 20-year high; it fell back to 7.6% the following month. “The bank was always trying to find an excuse not to raise interest rates,” comments Stephen Brown at Capital Economics. “At the start of this year, the market was pricing in a rate rise from the Bank of Canada, but it just kept finding excuses not to act. I think—even though we can’t blame them for not predicting the war on Ukraine—they were too slow to lift off.” Along with the US Federal Reserve, Canada’s central bank turned around over the second part of the year. “Even though [the bank] took a long time to become hawkish,” Brown adds, “it became so very quickly. It hasn’t messed around.”

CHILE

Rosanna Costa | GRADE: Too Early To Say

As she was appointed less than a year ago, in February 2022, any judgment of her leadership would be premature. So far there are no indications of substantial changes in policy. The Banco Central de Chile (BCC) continued the aggressive policy of interest rate increases begun in July 2021, without success: inflation soared above 13% this year.

“Moving forward, we expect the bank will continue its hiking cycle at a slower pace, as it has signaled its strong commitment to reining in price growth and expectations,” says Fitch’s Trahan. “This commitment has not been notably affected by the resignation of former BCC President Mario Marcel. (He is now the finance minister. His replacement, Rosanna Costa, has overseen continued rate hikes as inflationary pressures accelerated following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.” Chile will see one of the steepest growth slowdowns in Latin America in 2022, falling from 11.7% in 2021 to 1.9% this year, says Fitch.

COLOMBIA

Leonardo Villar Gómez | GRADE: A–

Colombia’s growth in 2021 was strong at 10.6%, with the central bank’s forecasts easing to 5.6% for 2022 and 3.4% for 2023. The central bank (Banco de la República, or Banrep) made five interest rate hikes in 2022. “Banrep focused on stopping inflationary pressures and avoiding a weakening of the peso,” comments Luis Arturo Bárcenas, senior economist at Ecoanalitica.

The shift to the left in the last presidential election worries some. “With Gustavo Petro in Bogotá and Gabriel Boric in Santiago, they also put pressures on the currencies, because of the political uncertainties,” says Marcelo Carvalho, the head of Global Emerging Markets Research at BNP Paribas in London. “So, in these countries there was additional concern for the central bank—that a weakening currency could boost further inflationary pressures.” Still, Banrep continues to enjoy a high degree of independence.

COSTA RICA

Róger Madrigal López | GRADE: Too Early To Say

Róger Madrigal López was appointed as governor of the Banco Central de Costa Rica in May. He has been working at the central bank for 40 years and most recently was the head of the economic division. Although it is too early to assess his tenure, Madrigal López has a reputation for fighting inflation: In 2004, he was in charge of a strategic plan to reduce inflation. At the end of July, the Central Bank of Costa Rica ordered a 200-basis point (bp) increase in the policy rate, to 7.5%—the sixth consecutive rate hike since the end of 2021.

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

Héctor Valdez Albizu | GRADE: B+

In 2022, the Banco Central de la República Dominicana has maintained its reputation for independence, defending the currency and fighting inflation. It started a tightening cycle in November 2021 and had six consecutive raises of the key interest rate, which stood at 7.75% in July. “We expect the key rate to end the year at around 8.5%,” says Alejandro Grisanti at Ecoanalitica. “As a matter of fact, the underlying inflation, excluding more-volatile components, has hinted at some moderation.”

EASTERN CARIBBEAN

Timothy Antoine | GRADE: B–

The monetary authority for a group of eight island economies—Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Saint Lucia—Eastern Caribbean Central Bank (ECCB) has maintained a stable financial system. The economy of the eight countries has been particularly slow to emerge from the Covid pandemic, while inflation is eroding income and lowering output. “Real GDP is projected to grow by 7.5% in 2022, leaving output still well below the pre-pandemic level,” said the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in a July report on the Eastern Caribbean Currency Union. And “fiscal deficits are projected to remain sizable.” Non-performing loans may rise with the expiration of the ECCB’s loan moratorium, notes the report.

Still, the IMF acknowledges the financial system has adequate capital and liquidity buffers. Also, the IMF welcomes recent steps by the ECCB to integrate climate risks into supervisory and regulatory frameworks and continue building climate resilience via new infrastructure. DCash, the central bank’s digital version of the Eastern Caribbean Dollar, suffered a major crash in February but was restored in March. The IMF report stresses the need to “raise public awareness and improve communication with end-users, reinforce capacity and fully implement safeguard measures.”

ECUADOR

Guillermo Avellán Solines | GRADE: C+

Ecuador, which defaulted two years ago, rebounded to 4.2% GDP growth in 2021 with macroeconomic management and a boost from high oil prices, according to the IMF. “Because Ecuador’s economy is dollarized, the Banco Central del Ecuador is limited in what it can do,” notes Fitch Solutions’ Trahan. “That said, the bank’s foreign reserves, which support the economy’s dollarization, have steadily risen this year as a product of higher prices for the country’s oil exports.”

Guillermo Avellán—an economist appointed in June 2021 as general manager of Ecuador’s central bank—promoted some institutional changes aimed at giving the central bank power to set interest rates and promote financial inclusion. He has commented that for a country with a dollarized economy, the stability of the financial system is of paramount importance because of the lack of a lender of last resort. Avellan also promoted the elimination of charges for sending and receiving money transfers—critical where remittances are a key macroeconomic element.

EL SALVADOR

Douglas Pablo Rodríguez Fuentes | GRADE: C–

The US dollar is currently the main currency for El Salvador and its monetary policy remains an independent variable. According to the World Bank, the Salvadoran economy will grow 2.7% in 2022 and 1.9% in 2023. The government experiment introducing bitcoin as legal tender—the first country to do so, in 2021—led to a decline in trust, with public bonds trading at around 30% of face value. And bitcoin’s price fell dramatically over 2022.

According to the IMF, the country is on an “unsustainable path,” with financing needs set to surpass 15% of GDP this year. In July, the government launched a bond buyback to show international markets its willingness to repay the debt. “Reviewing the data for the first quarter of the year raises some alarms,” says Jesús Palacios Chacín, senior economist at Ecoanalitica. He expects El Salvador’s growth to be among the weakest in Central America.

GUATEMALA

Sergio Recinos Rivera | GRADE: B+

The quetzal is the currency of Guatemala, named after the national bird. Banco de Guatemala, or Banguat, maintained sustained economic expansion in the first quarter of 2022. GDP rose by 4.5% and the economy appeared relatively protected from inflation and the war in Ukraine. Banguat foresees GDP growth settling at around 4% for all 2022, supported by the recovery of international tourism. Moody’s, changing Guatemala’s outlook to stable, commented, “The stable outlook reflects our expectation that … the government’s long-standing commitment to prudent fiscal and monetary policies will help Guatemala maintain its debt close to the current levels, despite pressures arising from high poverty levels and relatively weak institutions.”

HONDURAS

Wilfredo Rafael Cerrato Rodríguez | GRADE: B

The Banco Central de Honduras successfully supported economic growth in the wake of the pandemic hurricanes Eta and Iota. According to the IMF, GDP grew by 12.5% in 2021—the country’s best performance since 1977. Today, the country faces higher-than-expected inflation and higher-than-planned public debt. Over the first part of 2022, the Central Bank of Honduras funded public debt with at least two separate loans—one considered temporary, to be repaid in six months. Moody’s July update on the country noted that “the credit profile of Honduras balances a relatively low debt burden and steady real GDP growth against low levels of economic development and a weak institutional framework. Debt metrics deteriorated moderately in 2020 but have since improved.”

JAMAICA

Richard Owen Byles | GRADE: B–

Jamaica remains affected by subpar growth in comparison to peers in the region—and also by inflation, which averaged 8.6% from 2000-2019. Perhaps as a result, the Bank of Jamaica shows great determination to pay down public debt and fight inflation, raising key rates several times, from 0.5% in September 2021 to 5.5% in July 2022.

“The BOJ’s mandate was revised in 2020 to set a fully fledged inflation-targeting regime,” says Fitch’s Trahan. “The spike in prices since mid-2021 is the first major test of the BOJ’s commitment to its inflation target, and the central bank has responded proactively with an extended series of rate hikes. The bank’s hawkish response will likely support its inflation-fighting credibility and is in line with our expectation that the central bank would generally adhere to IMF-prescribed policy.” Jamaica’s recovery will be slow, he adds, in line with its regional peers, and vulnerable to a loss of US, Canadian and other tourists suffering diminished spending power due to economic strains in their home countries.

MEXICO

Victoria Rodríguez Ceja | GRADE: Too Early To Say

Outgoing Governor Alejandro Díaz de León started it in June 2021; and since then Mexico’s central bank, Banxico, has announced a total of nine rate increases, from 4% to the current 7.75%. Some expect rates to climb above double digits by the end of the year. An appointee of left-leaning President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), Victoria Rodríguez Ceja sparked investor concerns—particularly after AMLO clashed with Banxico over access to funds disbursed by the IMF in August 2021, says Trahan. “However, thus far in her term, Rodríguez Ceja has voted in line with the majority, supporting hawkish policy and generally quieting these concerns,” he adds.

NICARAGUA

Leonardo Ovidio Reyes Ramírez | GRADE: C

Banco Central de Nicaragua raised its monetary reference rate to 5.5% from 5% in August, in a move following a general international trend. The country, which has a large dependence on the international prices of oil, has seen high inflation and a series of downward revisions to growth in 2022. Estimates include an optimistic 5% from the central bank, but the World Bank puts it at 2.9% and the Economic Commission for Latin America at 3%. This summer, the United States and then Canada blacklisted the president of the Central Bank of Nicaragua, Leonardo Ovidio Reyes Ramírez, alleging human rights abuses and efforts to undermine democracy. But Moody’s gives Nicaragua a B3 stable rating, noting that “upside and downside risks to Nicaragua’s credit profile remain balanced. Moody’s believes that the sovereign’s strong adjustment capacity will continue to guide fiscal policymaking as the economy returns to a steadier equilibrium.”

PARAGUAY

José Cantero Sienra | GRADE: A

Banco Central del Paraguay confirmed its tradition of stability with a solid monetary policy, first during the pandemic and later the Ukraine war. In July, it corrected its inflation estimates for the year up to 8.8%, well above the 4% target, and revised its growth estimate to 0.2%.

In July, Moody’s confirmed the government of Paraguay’s long-term Ba1 issuer ratings and senior unsecured bond ratings and changed the outlook to positive from stable because “a track record of solid growth and prudent fiscal policy are supporting Paraguay’s positive credit momentum; fiscal and debt metrics compare favorably with those of Baa-rated sovereigns.” In August, the Financial Action Task Force of Latin America decided not to include Paraguay in the gray list despite a current investigation of the country’s former President Horacio Cartes.

PERU

Julio Velarde Flores | GRADE: A

Peru’s central bank started an aggressive cycle of monetary tightening in August 2021, doubling its benchmark policy rate to 0.5%. Since then, it has raised its rate 12 times, to 6% in July. Despite this, inflation reached a 25-year high in the country amid street protests against the increased cost of living. Peru is facing one of the steepest slowdowns in the region. “Peru’s constant political gridlock has thus far prevented President Pedro Castillo from implementing much of his leftist policy agenda, keeping Peru’s business-friendly operating environment in place,” says Fitch Solutions’ Trahan. Julio Velarde, now in his fourth consecutive term, has led the central bank since 2006. He showed a strong and immediate response to the surge in inflation. “The [inflationary] price rises are not only external; they also correspond to local dynamics more persistent than anticipated,” says Diego Santana Fombona, an economist at Ecoanalitica. “However, the real interest rate remains at negative levels, which is why the incentives to obtain credit are maintained, just as, to date, activity figures continue to show sustained growth, despite a slight slowdown.”

SURINAME

Maurice Roemer | GRADE: C+

Suriname, South America’s smallest country, was carrying an estimated total debt of just $3.4 billion at the end of 2021 when the IMF approved $673 million in new funds, based on the country’s plan to address fiscal and external imbalances.

Now, in the fall of 2022, Suriname is in default on its external debt and wrangling with international creditors. A March review by the IMF says the country’s recovery program remained “on track despite difficult social and economic conditions.” The central bank, in particular, is praised in the executive board discussion for its commitment to “achieving a downward path for inflation and maintaining a market-determined exchange rate,” and the report notes that “proactive steps have also been taken to address vulnerabilities in the banking system.”

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

Alvin Hilaire | GRADE: B–

Higher international prices of oil and gas are supporting economic growth in 2022, with S&P projecting a GDP increase in 2022 of 4.5% and of 3.9% in 2023. The central bank cut the key repurchase rate to 3.5% at the start of the pandemic in order to support the economy and has left it unchanged. “A heavily managed exchange rate and a small open economy effectively limit the role of monetary policy,” says S&P, which revised the nation’s outlook from stable to negative. The central bank has traditionally kept a low interest rate.

UNITED STATES

Jerome Hayden Powell | GRADE: B+

US Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell was late in tightening policy as inflation rose, and now he could be the first head of the Federal Reserve to face stagflation since Paul Volcker at the beginning of the ’80s. Several Fed board members expressed self-criticism for having been slow to act. Observers such as former head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, William Dudley, commenting on June’s 75 bp hike, stressed how sudden moves by a central bank can have bad impact. “When the Fed changes their mind at the last minute like this,” said Dudley, “it does have the potential to undermine the credibility” of its critically important communication with markets and the public. Still, the Fed gets credit for self-correcting. “Having acknowledged the mistake,” notes Michael Pearce, senior economist at Capital Economics, “they have moved very quickly back to neutral setting.”

URUGUAY

Diego Labat | GRADE: A–

The Banco Central del Uruguay, which only in 2020 adopted a monetary policy rate, has aggressively increased the cost of money—ordering seven straight rate hikes since August 2021, for a total of 475 bps, to 9.75%. Central Bank Governor Diego Labat says that 2022 will see a year-end inflation at around 8.5%, well above the 5.8 % of 2021. But he is determined that, no matter what is happening in the rest of the world, Uruguay will bring it down. “Inflation in the United States, in Europe and in the region is on the order of 10%. Ours is below 10%,” he said at a parliamentary presentation in July. “The issue is how long this is going to last. I want to be clear about that. In other words, in six months we will no longer have this inflation.”

VENEZUELA

Calixto José Ortega Sánchez | GRADE: F

The Venezuelan economy remains trapped in a state of high inflation, currency depreciation and international scorn—although this year’s sharp increase in oil prices has been a great help. Still, in July, the British government (which supported opposition candidate Juan Guaidó) refused Banco Central de Venezuela (BCV) Governor Calixto Ortega Sánchez’s demand to repatriate roughly $1 billion worth of Venezuelan gold that had been deposited with the Bank of England.

While this year’s soaring oil prices are bolstering the economy, even with production below prior capacity, there is great pressure on all non-oil sectors. “We expect that the Venezuelan economy will grow at least 9.7% by 2022,” says Ecoanalitica’s Bárcenas; but he cautions that “inflation and the exchange rate will continue to yield to the limitations that the BCV continues to impose, with annual price growth [expected] of 150.8% and an official closing exchange rate of 7.97 Venezuelan bolívares per US dollar for this year.”

—The Americas by Tiziana Barghini

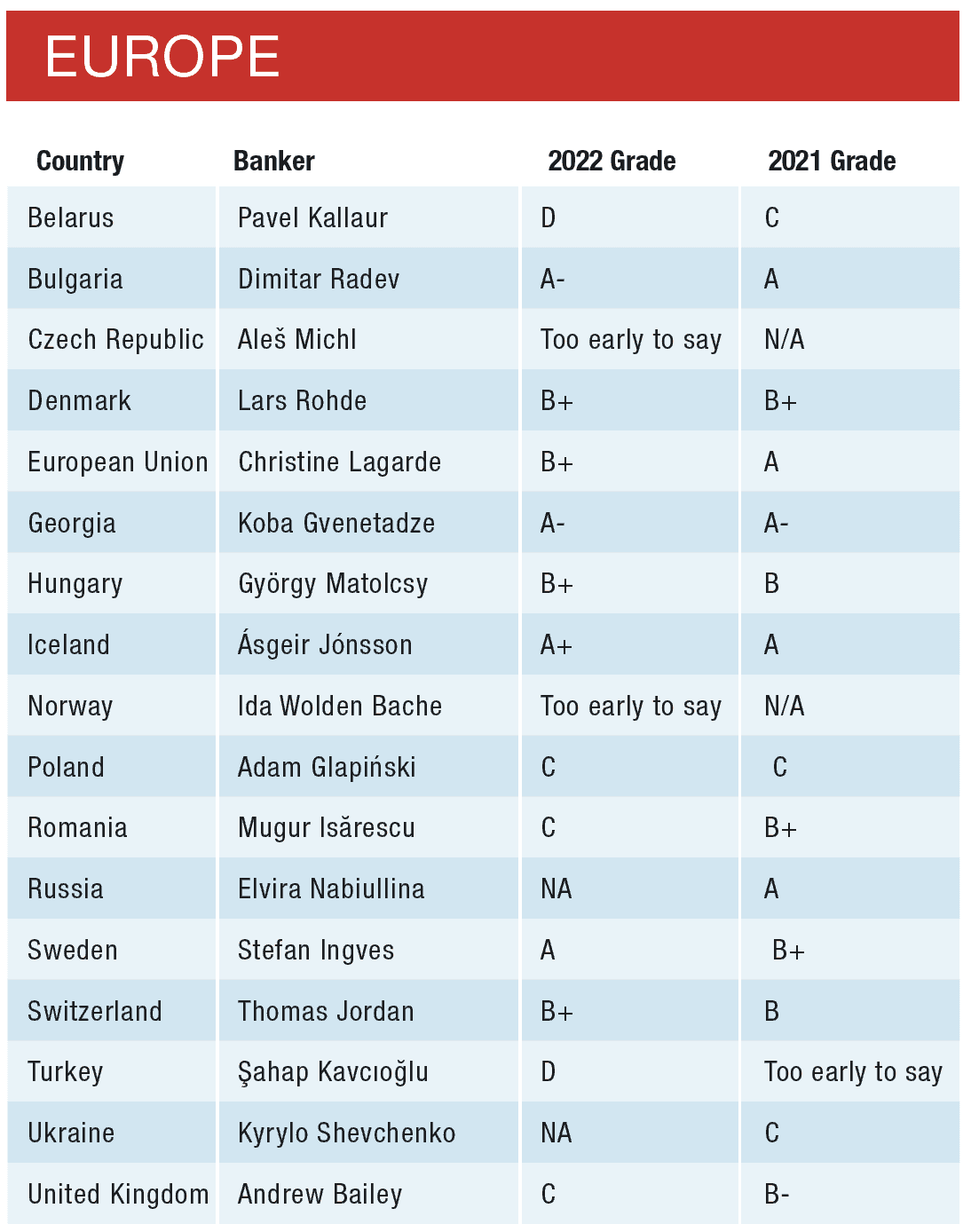

EUROPE

BELARUS

Pavel Kallaur | GRADE: D

Rising global commodity prices and domestic inflation are taking their toll on the Belarusian economy, which according to the World Bank will see its GDP contract by almost 3% this year. Kallaur and the National Bank of the Republic of Belarus responded by raising the key policy rate: first to 9.25% in 2021; then, in February this year, with the Belarusian ruble losing 20% against the euro and dollar following the Russian invasion, by another 275 basis points (bps), to 12%. Further increases to stabilize the ruble are expected in the near term; but according to the Belarus in Focus Information Office, a Warsaw-based nonprofit, nonpartisan organization working closely with Belarusian and international journalists, the central bank is losing its influence on monetary policy as Alexander Lukashenko’s regime is said to be using force and intimidation to maintain loyalty among bankers and technocrats.

BULGARIA

Dimitar Radev | GRADE: A–

Having recovered well from the pandemic, Bulgaria’s economy is now battling inflation expected to exceed 11% in 2022 according to the IMF. The central bank has revised its growth forecasts downward from initial projections of more than 3% growth to less than 2% for both 2022 and 2023. However, Radev, whose term as central bank governor officially ended last year, has not followed his Central European peers in raising rates—largely because the currency, the lev, is pegged to the euro. Bulgaria says it is still on track to join the eurozone from January 1, 2024. This pronouncement comes despite bickering between the ruling party and opposition, slowing efforts to find a replacement for Radev. Whoever steps into his shoes will be responsible for finalizing preparations for Bulgaria to join the eurozone, an eventuality likely to be among Radev’s lasting legacies as central bank governor.

CZECH REPUBLIC

Aleš Michl | GRADE: Too Early To Say

With Jiří Rusnok’s term of office as central bank governor expiring in June, Michl, who is an economist by training and has worked as a journalist and economic adviser to the Czech Ministry of Finance and later the former Czech Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, left no one guessing how he would steer the central bank. “I will propose at the first Bank Board meeting in the summer, in my new role as governor that interest rates remain stable for a while,” he said when his appointment was formally announced in May. While most central banks in the region are raising interest rates to counter rapidly rising inflation, Michl’s “dovish transformation” proposes to end rate hikes. He expects inflation to be back on target in two years and notes that higher rates are not having much impact in reducing inflation.

DENMARK

Lars Rohde | GRADE: B+

After 10 years as governor of the Danmarks Nationalbank, Lars Rohde has announced he will be retiring at the end of January next year. The first central banker to introduce negative policy rates, in July 2012, Rohde will be leaving at a time when most central banks, including Denmark’s, are reversing the past decade of easy money. In a March 2022 assessment of the impact of the Ukraine war on the Danish economy, Rohde said GDP growth would contract by approximately one percentage point and inflation increase by approximately two percentage points this year. In step with European Central Bank (ECB) monetary policy (the Danmarks’ main remit is to keep the currency stable within a narrow peg to the euro), the bank, in July, raised the current-account rate, the rate of interest on certificates of deposit, and the lending rate by 0.5 percentage points.

EUROPEAN UNION

Christine Lagarde | GRADE: B+

Last year, Lagarde was adamant that the ECB would not act on what she termed “temporary inflation.” What a difference a few months make. With worsening inflation and war in Ukraine, Lagarde had to do a quick about-face: The era of negative interest rates and asset purchases is coming to an end. The ECB is calling it a “normalization.” Lagarde and the ECB certainly didn’t react as swiftly as other central banks to burgeoning inflation, but over the summer they tried to make up for lost time by hiking the three key ECB interest rates by 50 bps in an effort to bring inflation nearer to the 2% target. According to Eurostat, euro area annual inflation was expected to reach 9.1% in August. Given the challenges ahead—the eurozone is thought to be entering a recession—the ECB is taking a “meeting-by-meeting” approach to setting rates, hoping to thereby reach inflation objectives more quickly.

GEORGIA

Koba Gvenetadze | GRADE: A–

Gvenetadze has never been one to balk at doing what is needed to support the real economy, but he has his work cut out for him, not least because Georgia is geographically close to Ukraine. According to a June 2022 report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the war is expected to “dampen growth, raise inflation and widen the current account deficit.” In March, the National Bank of Georgia hiked the key policy rate 50 bps to 11%, a 14-year high, where it has since remained. “The central bank’s monetary policy stance remains appropriately focused on bringing down high inflation,” the IMF stated in a June press release announcing a $280 million standby arrangement for Georgia. “The authorities are committed to maintaining exchange rate flexibility, strengthening reserves and enhancing the central bank’s communication strategy. They have managed the initial impact of sanctions, with the central bank requiring banks to adhere to international sanctions, which has limited risks.”

HUNGARY

György Matolcsy | GRADE: B+

While the second quarter saw Hungary notch GDP growth of 6.5% year-on-year, ING analysts warn of a “technical recession” in the year’s second half. Inflation continued to accelerate in August, to 15.76%, the highest since May of 1998. Retail sales are falling and unemployment is rising. So far, Matolcsy and the Magyar Nemzeti Bank (MNB) have maintained a hawkish outlook, delivering a decisive 100 bps worth of increases in the base rate, which currently stands at 11.75%. But with inflation expected to peak in the 22% y-o-y region by the end of this year, according to ING analysts, the question is how far Matolcsy is willing to go. Analysts say the key rate could reach as high as 14% by December. But the MNB isn’t relying just on higher interest rates to mop up excess liquidity. The bank has also raised the reserve ratio for banks, including setting a new minimum daily reserve at 5%. Matolcsy’s hawkishness appears to have satisfied analysts’ expectations for now.

ICELAND

Ásgeir Jónsson | GRADE: A+

With 80% of the country’s energy coming from renewables, Iceland’s economy is better protected from rising energy prices than is the rest of Europe. However, the rising cost of living, especially for housing and domestic goods, has Jónsson worried—worried enough to be the first Western central bank governor to start tightening monetary policy, in early 2021. With the central bank initially forecasting inflation to peak at 11% later this year, Jónsson acted swiftly and decisively, instituting rate hikes of 75 bps to 100 bps. At its August meeting, the bank hiked interest rates by another 0.75 percentage points to reach 5.5%; and Jónsson has not ruled out further rate hikes to tackle “persistent house-price inflation and higher global inflation.” He is also not afraid to use other tools in the central bank’s toolbox—capping loan-to-value ratios on residential mortgages and debt service-to-income ratios—to control price inflation in Iceland’s housing market.

NORWAY

Ida Wolden Bache | GRADE: Too Early To Say

While her predecessor Øystein Olsen instituted some of the most drastic rate cuts in the Nordic region during the pandemic, the Norges Bank’s first ever female governor hasn’t wasted any time instituting a series of rate hikes, as inflation rose to its highest levels since 2008. Having already raised the policy rate to 1.25%, in August, Wolden Bache and the bank’s Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Committee hiked the key policy rate to 1.25%, then another 0.5%, to 1.75%. With food and energy prices ticking upward over the summer, Wolden Bache has hinted at further policy rate increases in the fall. “Low and stable inflation is important for the economy to function well and is a prerequisite for predictability,” the governor stated following August’s rate hike. “I don’t think any of us want to return to the Great Inflation of the 1970s.”

POLAND

Adam Glapiński | GRADE: C

Glapiński dismissed concerns about inflation last year, remaining dovish even as other central banks started inching interest rates up well in advance of more dire inflation forecasts. The Narodowy Bank Polski has steadily increased the reference rate over the past few months, with the last rate hike, to 6.5%, coming in July. But it looks like Glapiński will need to do more, judging by August’s surprise uptick in consumer price inflation, which rose to 16.1% year-on-year in August from 15.6% y-o-y in July. Glapiński may be looking for a peak in the rate hiking cycle, but ING analysts are adamant that further rises in inflation after the summer holidays and in early 2023 mean the hiking cycle is far from over.

ROMANIA

Mugur Isărescu | GRADE: C

In June, the IMF warned that Romania “is facing adverse spillovers from the war in Ukraine and rising inflation.” At its meeting in August, the National Bank of Romania (NBR) tightened its main policy rate to 5.5% from 4.7%. According to Focus Economics, the policy rate could end the year at 6.3%, coming back down to 6% in 2023. However, compared to his Central and Eastern European peers, Isărescu has less leeway to hike rates, given fears about the impact on the Romanian economy. Hence, analysts remain skeptical about the NBR’s ability to meet its 2.5% inflation target. “Considering that the bank hiked too little to control expectations and that it remains reluctant to tighten as it aims to avoid a recession, despite rather reasonable growth currently and large EU funds available, we do not believe in a return to the target in 2024 or later, unless a deep recession materializes,” states economist Nicolaie Chidesciuc of J.P. Morgan.

RUSSIA

Elvira Nabiullina | GRADE: No Grade

Due to the war in Ukraine, Global Finance editors have decided not to award grades to the Russian and Ukrainian central bank governors this year. Still, it is worth noting that Nabiullina has steered the Russian economy and the ruble through one of its most challenging periods to date, under an unprecedented level of economic sanctions and the freezing of approximately $300 billion of Russian central bank assets globally. Amid rumors that she wanted to leave the central bank following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the ruble lost half its value in February. Nabiullina immediately went into defense mode, shoring up the currency by boosting the key interest rate from 9.5% to 20%. It was this step that led to the ruble’s remarkable recovery. Under Nabiullina’s guidance, the central bank is also pondering a plan to buy as much as 70 billion in yuan and other “friendly” currencies to help with the further de-dollarization of its reserves. However, the war will shrink the Russian economy. According to Russian central bank forecasts, GDP will decline this year by 4% to 6%. Over the next year, according to Nabiullina, GDP will edge down by 1% to 4%.

SWEDEN

Stefan Ingves | GRADE: A

Stefan Ingves, who swam against the tide of monetary policy, will finally bow out as governor of the Sveriges Riksbank at the end of this year. Having begun his service in 2006, he has seen his term of office extended twice. For the past few years, he was among the camp of central bankers who presided over zero-interest or reference rates. The pandemic saw him embark on a relatively large asset-purchasing program, including purchases of corporate bonds for the very first time. Now he is departing at a time when Sweden’s 2%-inflation-targeting regime, which was first introduced in 1995, is experiencing its first real test. The bank’s policy rate is expected to be close to 2% by the start of next year to contain rising inflation that is likely to remain above 7% for the remainder of the year, according to the Riksbank’s July monetary policy report. This is what Ingves means by “acting forcefully” to rein in inflation, which he stated in August is “far off the mark.” He will be replaced by the current director of the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority, Erik Thedéen.

SWITZERLAND

Thomas Jordan | GRADE: B+

In June, Jordan and the Swiss National Bank finally relented, shrugging off 15 years without increases in its policy rate with a 0.5 percentage point hike; but at minus 0.25%, it is still in negative territory. Jordan still seems to be trying to distinguish between temporary and sustained inflationary pressure, judging by his comments at the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium in August. Inflation is still relatively low in Switzerland compared to other countries, holding steady at 3.4% to 3.5% for most of the summer. Jordan was quick to act, even though inflation is likely to remain mild for the Swiss “in the broader European context,” says Focus Economics, “thanks to the country’s limited reliance on fossil fuels for electricity generation, ingrained low inflation expectations, the franc’s appreciation this year against the euro, and mild wage growth.”

TURKEY

Şahap Kavcıoğlu | GRADE: D

Turkey’s central bank has never been one for orthodox monetary policy. Following a succession of rate cuts during the pandemic at the behest of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, raising concerns about political interference in monetary policy, the central bank is now battling skyrocketing inflation—which stood at over 80% in August, a 24-year high. Turkey’s central bank has lurched from a currency crisis to an all-out economic one, and the revolving door of the central bank’s governorship hasn’t helped matters; but Kavcıoğlu has lasted surprisingly longer than some predecessors. When downgrading Turkey to B+ negative watch in February, Fitch Ratings said it “does not expect the authorities’ policy response to reduce inflation, including foreign exchange-protected deposits, targeted credit and capital flow measures, will sustainably ease macroeconomic and financial stability risks.” Fitch also noted a potential for “additional destabilizing policy easing or stimulus policies ahead of the 2023 general elections.” In July, Fitch further downgraded the country to B.

UKRAINE

Kyrylo Shevchenko | GRADE: No Grade

When Shevchenko, a former chairman of state-owned Ukrgasbank, became the central bank chairman in 2020, he promised to defend its independence. But under martial law, imposed since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, Shevchenko and the central bank have had to navigate a tricky route between stabilizing the economy, minimizing panic and supporting the citizenry by setting up fundraising accounts to directly receive donations from inside and outside the country for the Ukrainian army and humanitarian needs. The bank has also bought war bonds to finance critical expenses of the government. The task for Shevchenko is daunting. Fitch Ratings estimates inflation will accelerate from 22.2% in July to 30% by the end of this year “due to monetary financing, ongoing supply chain disruptions, weak monetary policy transmission and the hryvnia depreciation, and to remain high in 2023, averaging 20%.”

UNITED KINGDOM

Andrew Bailey | GRADE: C

With the UK suffering the highest inflation rate in the G10 (10.1% in July), all eyes are on Governor Andrew Bailey. The bank’s mandate is to maintain monetary and financial stability, but Bailey was slow with interest rate hikes, which came only in August when the bank rate increased by a mild 0.5 percentage points, to 1.75%. The UK’s new prime minister, Liz Truss, clearly had the Bank of England and Bailey in her sights during her leadership campaign, when she blamed the bank for letting inflation reach new highs. Bailey faces a multitude of economic headwinds, not least of which is energy-induced inflation. Despite a government support package for rising energy prices being announced by the Truss government, Bailey may be forced to hike rates much further than he would like. September’s mini-budget, which saw sweeping tax cuts announced to ward off a deep recession, could fuel inflation even further.

—Europe by Anita Hawser

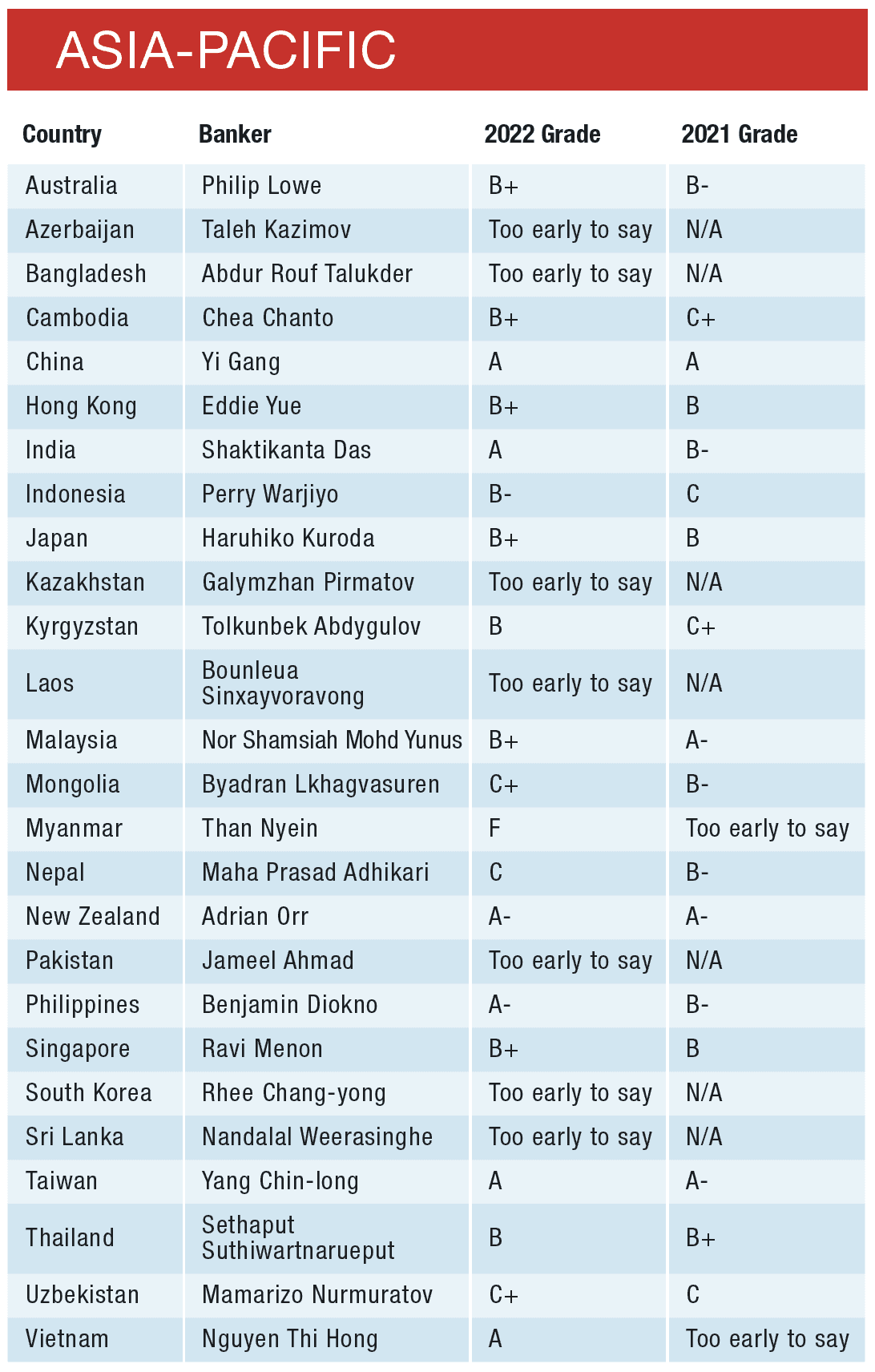

ASIA-PACIFIC

AUSTRALIA

Philip Lowe | GRADE: B+

The sudden updraft of inflation that emerged in Australia during the first quarter of 2022 followed years of notorious underperformance by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on inflation targets—indeed, deflation beckoned in 2020 as prices fell 0.9% according to the IMF, prompting Governor Philip Lowe to state bluntly that interest rates would remain subdued until 2024. That guidance was misplaced: Consumer price inflation hit a 20-year high of 5.1% in the three months to March, albeit propelled largely by the war in Ukraine. This prompted the bank to embark on its most aggressive rate tightening in 30 years, with three successive 50 basis point (bp) hikes of the benchmark cash rate in the first half, taking it to 1.35% from the record 0.1% lows of the Covid pandemic—accompanied by the RBA’s quantitative easing (QE) targeting the yield curve. The QE withdrawal could have been exercised with more finesse; but the 4.7% GDP growth of 2021 according to the IMF, near-full employment, stable Aussie dollar and low endogenous inflation are feathers in the RBA’s cap, as is the willingness to tighten early.

AZERBAIJAN

Taleh Kazimov | GRADE: Too Early To Say

By regional standards, the Central Bank of Azerbaijan (CBA) held to a relatively conservative monetary stance during the pandemic, reducing the refinancing rate by 100 bps, to 6.5%, and allowing macroprudential initiatives to do the rest. A solid GDP growth rate of 5.6% last year vindicated this approach; and, as with Australia, much of the inflationary pressure that emerged early this year in Azerbaijan’s economy derived from rising import costs. Against the backdrop of a comfortably stable manat (with the viability of the de facto dollar peg reinforced by a 22.5% current account surplus) and a buoyant Sofaz (the national oil fund), the CBA’s monetary prudence—the rate corridor was raised and the refinancing rate increased from 6.25% to 7.75% over the review period—is likely to have kept a lid on underlying inflation. A full-year reading is required, against a backdrop of falling import inflation, contained by a nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) appreciation dynamic.

BANGLADESH

Abdur Rouf Talukder | GRADE: Too Early To Say

For Bangladesh Bank (BB), as with many other central banks in the Asia-Pacific region (APAC), the mandate was reasonably met during the first half of the review period: Post-Covid GDP growth was solid at 5.6%, while inflation modestly overshot BB’s 5% target by 0.6% and the taka was steady. However, by mid-2022, the taka was devalued by 9.5%; importers struggled with an onshore shortage of dollars; energy and food costs ballooned due to the Ukraine conflict; and inflation ran rampant. Having burned through central bank foreign exchange reserves, a call went out for International Monetary Fund (IMF) support. But the structural weakness of the Bangladeshi economy and the government’s 60% control of the central bank produce a vulnerability to externalities such as the inflation shock of 2022.

CAMBODIA

Chea Chanto | GRADE: B+

National Bank of Cambodia (NBC) has stood out in Southeast Asia for a willingness to adopt innovative policy, most notably in the championing of its central bank digital currency (CBDC), the bakong, which last year began to make strides in helping reduce Cambodia’s dependence on the US dollar and open digital financial channels to its chronically underbanked population. Holding the post of NBC governor since 1998, Chea Chanto is one of APAC’s longest-serving central bank governors, yet works with a young and tech-savvy team. The free digital wallet they developed for the bakong is now used by half of Cambodia’s population, and billions of dollars’ worth of transactions have been processed by the app in the past 12 months. This is a stellar achievement for a CBDC launched as recently as 2020. As a result, reliance on dollar cash may soon become a thing of the past in Cambodia. NBC moved last year to risk-based supervision of the banking sector, with a forward-looking bias, enhancing the transmission of macroprudential policies and ushering in an era of streamlined bank organizational structures and governance.

CHINA

Yi Gang | GRADE: A

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) presides over a banking system awash with liquidity, having injected a gargantuan $1.3 trillion since 2018 in the form of successive cuts to the RRR, to fulfil a mandate of economic growth and exchange rate stability.

The RRR has been exemplary as both an exchange rate tool and a growth tool, nimbly utilized. It was increased by two percentage points last December to halt an appreciating renminbi; and it was cut from 2.1% to 2% in April “to improve financial institutions’ ability to use foreign exchange funds,” according to a PBoC statement.

Achieving 8.1% GDP growth last year without igniting inflation and in the context of China’s profoundly troubled real estate sector—which threatens systemic financial instability—was an immense achievement. And the PBoC under Governor Yi Gang mustered a variety of policy instruments, utilizing structural selected credit via macroprudential tools, rather than aggregate credit that affects the entire economy and carries inflationary risk.

HONG KONG

Eddie Yue | GRADE: B+

At the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), the job of CEO Eddie Yue is less expansive than that of his regional peers, given that the key role of the HKMA is to maintain the stability of the Hong Kong dollar/US dollar peg. Short-term interest rate policy moves in lockstep with the US Federal Reserve. Inflation has remained muted, hitting a seven-month high of 1.9% in July. Deft use of the countercyclical capital buffer and the regulatory reserve—the former was held at its Covid-response 1% and the latter cut by 50 bps—helped maintain system liquidity and lending capacity last year. The HKMA has earned its innovation chops by working with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) to launch the e-HKD, or e-Hong Kong dollar. That currency is in the works, while a CBDC digital renminbi is already in use to fund cross-border payments with China.

INDIA

Shaktikanta Das | GRADE: A

Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Governor Shaktikanta Das must be commended for delivering barnstorming 8.7% GDP growth last year to the world’s fifth-largest economy—much as is the case in China, growth is the central bank’s core mandate—while also containing inflation, which came in at 5.5% in 2021, within the RBI’s 2% to 6% target. Monetary policy has been on a tightening trajectory: The repo rate was increased by 140 bps via three consecutive hikes this year, the first since 2020; and the RRR was restored to 4%, its pre-Covid level, in two stages last year. Both moves were appropriately hawkish in relation to global price pressures this year; and they typify the RBI helmsman’s cautious equilibrium, as do his warnings on a CBDC for India: He refuses to provide a timeline and reiterates the dangers of cybersecurity and counterfeiting within a CBDC.

Das was reappointed to another three-year term last October—a year longer than the usual reappointment—in recognition of the prestige he brought to the RBI during Covid, with the institution’s efforts doing most of the heavy lifting in the country’s pandemic response.

INDONESIA

Perry Warjiyo | GRADE: B–

“Dovish” best describes the stance of Bank Indonesia (BI) Governor Perry Warjiyo, who has kept the policy rate at 3.5% since February 2021 while regional peers around him tightened up. Nevertheless, BI has steadily moved to reduce the excess liquidity hanging in the banking system thanks to Covid stimulus measures. BI’s mantra is “pro-growth,” and it perhaps helps that Warjiyo and his team focus on the core inflation rate, which remained within the bank’s 2% to 4% target corridor during the review period, rather than the headline rate (which overshot the corridor by 1%). Still, growth was a relatively lackluster 3.7% in 2021. There remains underlying unease regarding BI’s independence and the issue of “burden sharing.” A third burden-sharing exercise amounting to the equivalent of $30 billion was closed in August 2021, wherein BI accepted the repo rate for holding government debt rather than the market rate, representing a saving in excess of 3%. Meanwhile the rupiah remained vulnerable to speculative attacks based on rate differentials, hitting a two-year low of 15,000 versus the US dollar in early July.

JAPAN

Haruhiko Kuroda | GRADE: B+

The Bank of Japan signally failed to generate inflation in 2021 while continuing to adopt the tools of the “Abenomics” era, targeting a 0% yield on the 10-year government bond, buying ETFs, REITs, corporate bonds and commercial paper. A minus 0.3% consumer price index (CPI) rate for 2021 must be judged a failure in relation to the BoJ’s 2% inflation target; but Kuroda’s commitment to dogged transparency via his pronouncement in late 2021 that the policy rate would remain low, at 0.1%, and that yield curve control would remain intact, should be commended given what happened in the first half of 2022. In the three months to June, nationwide CPI came in at an average 2.6%, modestly overshooting the BoJ’s target. The bank now forecasts 2.3% CPI for the fiscal year to 2023 but refuses to tighten policy—unlike regional peers—in what has been described as the world’s most dovish central bank policy.

KAZAKHSTAN

Galymzhan Pirmatov | GRADE: Too Early To Say

Fuel price inflation was the direct cause of riots in January that claimed hundreds of lives and prompted President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev to summon the support of Russian troops.

When trading resumed after the conflict had subsided, the National Bank of Kazakhstan was forced to use up $240 million of reserves to support the tenge and to continue its rate hiking cycle, moving from 9.75% to 10.25% as it struggled to meet its 4% to 6% inflation target band. The national oil fund and state-owned companies sold more than $1 billion to prop up the tenge last December. Tokayev ordered Kazakhstan’s 16.1% inflation rate halved by 2025, in yet another war of words between the government and the central bank as the latter seeks to assert its independence.

KYRGYZSTAN

Kubanychbek Bokontayev | GRADE: B

The National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic hiked the policy rate four times last year, from 5% to 8%. Appointed at the end of Sept 2021, Bokontayev helped the som hold steady against the US dollar, and although inflation hit 11.9% in 2021, a disinflationary dynamic seems to have kicked in.

LAOS

Bounleua Sinxayvoravong | GRADE: Too Early To Say

For those who seek to find “the next Sri Lanka” in APAC, Laos has topped the list this year, as its economy struggles under the weight of a 65% debt-to-GDP burden, amounting to $14.5 billion (half owed to China). The nose-diving kip sank 13% against the dollar in July 2021 and at the same time by 8% versus the Thai baht—the currency of its regional key trading partner and crucial to tiny, landlocked Laos. Covid-19 hit the Laotian economy hard and demand has not recovered; unemployment is around 23%. Hence, the Bank of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic is caught between the need for monetary stimulus and the need to rein in inflation, which hit 30.1% in August, an all-time high. The central bank has attempted to control dwindling forex reserves by increasing the RRR from 1% to 3% for the kip and from 3% to 5% for foreign currency holdings, but this begins to seem like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

MALAYSIA

Nor Shamsiah Mohd Yunus | GRADE: B+

The Malaysian ringgit has been on a weakening trend versus the US dollar—and Singapore dollars, hitting a record 3.25 ringgits to the unit of its key trading partner across the Johor Strait in August. The blame in the former case lies with dollar strength and in the latter with Singapore’s managed exchange rate regime, which utilizes the forex rate to control inflation. Still, the risk of imported inflation remains high in such a scenario, particularly on intermediate and capital goods. Foreign debt service costs also rise. At the same time, the overnight policy rate was kept at a pandemic-induced record low 1.75% until May when it was hiked to 2%, which might seem rather too little and too late, as inflation hit the 3.4% mark. Bank Negara Malaysia also shows impressive involvement—alongside the central banks of Australia, Singapore and South Africa—in Project Dunbar, which aims to utilize CBDCs for international settlement via a shared platform developed by the BIS.

MONGOLIA

Byadran Lkhagvasuren | GRADE: C+

Bank of Mongolia’s (BOM) aggressive Covid stimulus—featuring a 5% cut in policy rates and a 5.5% cut in the RRR—manifested in delayed fashion, according to many Mongolia watchers. The surging local stock market, which was the world’s best-performing bourse, rallied up 130% last year on the back of excess onshore liquidity. It was a stimulus with unintended consequences—private consumption actually fell 4% in 2021—adding sharply to Mongolia’s debt-to-GDP ratio, which rose to 92%. And while inflation was inside the central bank’s 4% to 8% target band for 2021, at 7.1%, by June this year it had ballooned to 14.4%, exacerbated by China border bottlenecks and supply-side factors out of BOM’s control. Central bank operational independence was in the spotlight, as BOM conducted quasi-fiscal operations and the country entered the second half of 2022 facing possible stagflation.

MYANMAR

Than Nyein | GRADE: F

Myanmar’s economy shrank 18% last year. Had the country not endured a military coup and Covid, according to World Bank estimates, its economy would be 30% bigger. Amid the value destruction, the military junta announced in February that it is looking to establish a CBDC, perhaps with a joint venture partner, in order to “improve financial activities.” CPI was estimated by the World Bank at 17.3% in March, although data reporting is patchy and unreliable. Furthermore, there is currency market turmoil following Central Bank of Myanmar’s abandonment of the managed float exchange rate regime, an onshore shortage of dollars for export/import purposes, collapsing central bank reserves and production disruption due to civil conflict and power outages. Chaos reigns.

NEPAL

Maha Prasad Adhikari | GRADE: C

As tourism had dried up and foreign worker remittances declined, an official at Nepal Rastra Bank warned in April that central bank reserves were running so low that the country risked being unable to import items such as medical supplies, cars and petroleum products. The comments, which led to Gov. Adhikari being briefly suspended, echo troubles that brewed last year when the central bank’s quasi-fiscal directed-lending policies threatened a liquidity crisis, increasing the credit to core capital ratio from 85% to 90%. The Financial Action Task Force is auditing the bank for weak anti-money laundering measures.

NEW ZEALAND

Adrian Orr | GRADE: A–

At the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ), Governor Adrian Orr moved at the first signs of inflation, hiking the cash rate by 25 bps to 0.5% last October—having ended quantitative easing under the Large Scale Asset Purchase program three months earlier—as inflation rose to the highest level since 2009. The QE announcement came after the RBNZ had reduced weekly bond purchases to 220 million New Zealand dollars and caused a surge in two-year swap rates from 0% to 1%, signaling market normalization. RBNZ was the first developed nation central bank to tighten, which is perhaps not surprising, given that RBNZ pioneered formal inflation targeting over 30 years ago. The RBNZ’s loose monetary policy and QE was criticized in July by former Governor Graeme Wheeler for unleashing a 30% house price boom in 2021.

PAKISTAN

Jameel Ahmad | GRADE: Too Early To Say

State Bank of Pakistan began its tightening cycle quicker than any other developing country central bank in APAC, with then Governor Baqir hiking three times last year for a cumulative 275 bps, as inflation edged up, the trade balance deteriorated and the rupee put on Asia’s worst currency performance. Baqir’s stated aim of achieving positive real interest rates was abandoned early this year amid soaring inflation stoked by the 625 bps easing the State Bank of Pakistan executed in 2020 and a variety of supply-side shocks. The central bank tightened policy rates by 400 bps in the year to June—at which point CPI hit a 13-year high of 21.3%—to battle price pressures released by pent-up demand. Domestic economic conditions deteriorated sharply as the year progressed, in the face of onerous external financing costs and collapsing central bank reserves, forcing Pakistan to seek IMF assistance to the tune of around $41 billion of emergency funding.

PHILIPPINES

Benjamin Diokno | GRADE: A–

The outgoing governor of the Bangko Sentral Ng Pilipinas (BSP), Diokno took a gradualist approach to rate tightening as inflationary pressures built in the Philippine economy, tightening the benchmark rate by 25 bps in May to 2.25% for the first increase since 2018 as headline CPI hit 4.9%. This arguably weighed on the peso, which fell to its all-time lowest level in September as he was clearing his desk, and time will tell whether a more aggressive approach was justified.

But Diokno must be lauded for delivering stunning GDP growth, which hit 5.6% last year and is on target to clock the bank’s 7% to 9% official estimate for this year. The growth/inflation trade-off looks acceptable in such circumstances if the BSP average 4.6% estimate for 2022 is met—for much of 2021 it was contained within the bank’s 2% to 4% target band. The BSP executed a smooth withdrawal of the “QE-lite” bond-buying program, shifting to a regular facility that can be used to actively manage money supply, and brushed off lingering criticism of deficit monetization as it prepared to accept early repayment of a loan made to the government during the height of the pandemic.

SINGAPORE

Ravi Menon | GRADE: B+

Economic challenges in the city-state have been rising as the post-Covid recovery has taken shape: the worst labor shortage in two decades; inflation at a 14-year high, hitting 7% in July; and a widening inequality gap—measured by the Gini coefficient—loom large in Menon’s inbox. Singapore uses currency appreciation as a monetary policy tool, steepening the slope of the nominal effective exchange rate ($NEER) currency band, and its midpoint and width to tighten economic conditions. In April the Monetary Authority of Singapore moved the $NEER midpoint and its slope in an ultrahawkish take on inflationary pressures.

Menon has taken center stage globally this year in his efforts to coalesce policymakers and businesses around the climate agenda as he chairs the Network for Greening the Financial System, an international group of central banks and financial supervisors.

SOUTH KOREA

Rhee Chang-yong | GRADE: Too Early To Say

Named by South Korean President Moon Jae-in in March, Rhee replaces Lee Ju-yeol, who had served the legal maximum of two consecutive terms. Rhee has already stepped up with a 50 bp hike—the biggest increase since 1999—to counteract rising inflation and a falling won, one of the year’s worst-performing currencies in emerging markets. Rhee plans to keep monetary policy tight for some time and to keep a close eye on the US Fed.

SRI LANKA

Nandalal Weerasinghe | GRADE: Too Early To Say

Whether the boxes ticked in Sri Lanka over the past 18 months qualify the country as a “failed state” is a subjective call, but central banking in such circumstances becomes the stuff of nightmares. Offshore debt default, the collapse of forex reserves, capital flight and hyperinflation—to say nothing of violent civil protest—have been gifted to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka’s governor. Unsurprisingly in such circumstances, the country has had three governors over that period. Appointed in April 2022, Nandalal Weerasinghe raised the policy rate 700 bps in July as inflation hit 55%.

TAIWAN

Yang Chin-long | GRADE: A

Central Bank of the Republic of China’s Governor Yang Chin-long has helped deliver a global rarity to the country: continuous economic growth for the past five years, and in 2021 its highest in a decade as GDP rose 6.6%, boosted by soaring exports. Taiwan skirted global semiconductor supply chain bottlenecks, propelling the country’s current account surplus to 15% of GDP and helping boost the Taiwan dollar, the strongest currency in APAC last year. For a preeminent exporter such as Taiwan, forex stability is a key part of the central bank’s mandate; but this strength was welcome: It kept a lid on inflation, which was just 1.8%. The measured calibration that has become the hallmark of monetary policy at Taiwan’s central bank was in evidence in response to price pressures this year. CPI hit a 14-year high of 3.6% in June, and the policy rate was hiked in two stages to 1.5% from the record low 1.25% that prevailed last year. Yang declared the rate rise decision “very difficult,” but Standard Chartered economists in Taiwan believe CPI may have already peaked in the country.

THAILAND

Sethaput Suthiwartnarueput | GRADE: B

It’s perhaps surprising that the Bank of Thailand (BoT) under Governor Sethaput Suthiwartnarueput waited until August to increase policy interest rates for the first time since 2018, by 25 bps, following 2020’s three cuts in the one-day repurchase rate to an all-time low of 0.5% .

But much as with other central banks in Asia in the review period, the Jekyll and Hyde nature of prevailing conditions played havoc with the mandate. No sooner had BoT successfully defeated negative inflation than the specter of its opposite appeared, by August reaching a 14-year high in CPI of 7.9%—way above the central bank’s 1% to 3% target. The inflation dynamic was stoked by the inauspicious performance of the Thai baht, which shed 8% in the year to August, for one of the worst performances in Southeast Asia, amid ongoing fears of sustained and hefty capital outflows from dollar-based investors as the interest rate differential versus dollar assets widens.

UZBEKISTAN

Mamarizo Nurmuratov | GRADE: C+

Last year was not an easy one for the Central Bank of Uzbekistan. Uzbekistan’s economy is heavily dollarized—the foreign currency reserve ratio requirement was hiked 4% to 18% last year to address this—and there are low levels of intermediation, making monetary policy transmission a major challenge. Inflation was already up at 10.8% last year according to the IMF, thanks in part to strong credit growth of around 9% in the first six months of the year. The policy rate was set at 14%, with the corridor widened to 2% on either side, and the average coefficient of required reserves increased to 0.8% from 0.75%.

VIETNAM

Nguyen Thi Hong | GRADE: A

When Nguyen Thi Hong was elected the first woman governor of the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) in November 2020, she joined an elite group: A 2021 survey by the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum found that just 18 women held the rank of central bank governor at that time. Expectations were high, and Hong has not disappointed. In July 2021, she successfully negotiated with US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to resolve a dispute over the Vietnamese dong and allegations of currency manipulation. It was an auspicious start to her tenure, yet Hong faced some pressing challenges: to restore the flow of credit to a Covid-battered economy and the soured debt it left as a legacy, and to commence the immense challenge of restructuring the banking system and dealing with its “zero-dong” loss-making lenders. SBV has focused on macroprudential policies to boost credit growth. In January, Hong issued a directive designed to improve credit quality and through which loans to risky industries would be controlled, instructing the banks to keep the bad-debt ratio below 3%.

—Asia-Pacific by Jonathan Rogers

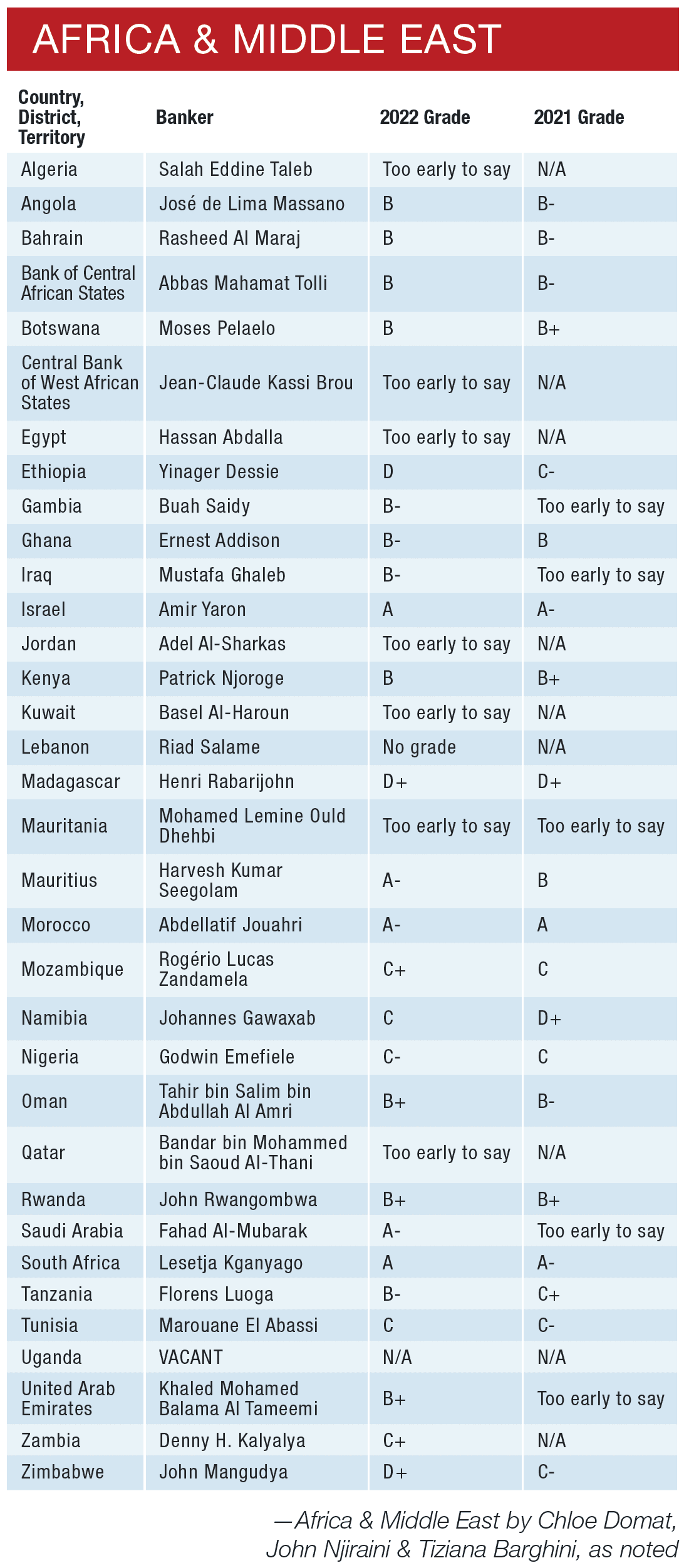

Middle East & Africa

ALGERIA

Salah Eddine Taleb | GRADE: Too Early To Say

The Algerian president dismissed Central Bank Governor Rostom Fadli in May 2022 and named Salah Eddine Taleb to replace him. Algeria should see a boost in external revenue as a result of the global hydrocarbon price rise but the country is also facing severe inflation and a dire need for public sector reform.

ANGOLA

José de Lima Massano| GRADE: B

In August, Angola went to the polls in a tightly contested presidential vote, and the incumbent secured another term. Oil accounts for 47% of Angola’s economy; but even with oil prices soaring, GDP growth is forecast to be a 3% in 2022, hinting at deep struggles throughout the economy. With inflation easing, oil boosting foreign exchange (forex) reserves and a stabilizing local currency, the National Bank of Angola (NBA) kept its benchmark rate at 20% for a sixth straight meeting in July. Inflation dropped below 20% in August, the lowest in more than two years. Though the banking sector remains largely stable and well capitalized despite huge exposure to the oil sector, NBA has created a financial stability department to enhance supervision. The bank is also implementing measures to make banks solid by increasing minimum core capital.

BAHRAIN

Rasheed Al Maraj | GRADE: B

With its currency pegged to the US dollar, the Central Bank of Bahrain (CBB) follows the US Federal Reserve’s lead on interest rates. The bank raised its key policy interest rates by 300 bps in 2022. By September, the one-week deposit facility reached 4%, the overnight deposit rate 3.75% and the lending rate 5.25%. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) praised the exchange rate peg as “an appropriate monetary anchor” that kept inflation under 4% until summer. Thanks to higher global energy prices, projected growth for 2022 stands at 3.5%. Increased hydrocarbon revenue is pushing economic indicators in the green: Debt-to-GDP ratio, one of Bahrain’s main weak spots, is set to lower from 130% in 2021 to 117%, while the budget deficit should drop to 3% in 2022 from 17% in 2020. The financial sector remains the backbone of Bahrain’s economy, with 362 financial institutions contributing almost 18% of GDP. Bahraini banks enjoy a strong reputation globally. To remain relevant in a fast-transforming environment, the CBB has an open approach to innovation, including cryptocurrencies, cloud and open banking.

BANK OF CENTRAL AFRICAN STATES (BEAC)

Abbas Mahamat Tolli | GRADE: B

An April decision by the Central African Republic (CAR) to adopt bitcoin as legal tender jolted the authority of the Bank of Central African States (BEAC), raising fears the move could have a contagious effect on its six members—Gabon, Cameroon, CAR, Chad, the Republic of the Congo and Equatorial Guinea. BEAC maintains that the decision goes against a “fundamental rule” of the bloc’s monetary union. Besides BEAC’s authority being undermined, Governor Abbas Mahamat Tolli is also under pressure—including accusations of nepotism. Nevertheless, he has maintained a steadfast focus on helping the region’s drive for economic growth. High crude prices have buoyed economic prospects, because oil accounts for more than 50% of revenue in five of the six nations. In July, BEAC maintained its policy rate at 4%, opting for status quo with inflation within target. With the region’s GDP growth projected at 3.5% in 2022, inflation is forecast to accelerate only marginally, to 3.8% from 1.6%.

BOTSWANA

Moses Pelaelo | GRADE: B

In February, Bank of Botswana (BOB) introduced a new monetary policy rate, using the yield on the main monetary operations instrument as the anchor instead of the official bank rate. In June, BOB increased its policy rate by 50 bps from 1.65% to 2.15% to contain inflation that increased to 14.3% in July, the highest since December 2008. Rising inflation, a depreciating local currency and external shocks are forecast to send growth to 4.3% in 2022, from 12.5% in 2021, according to the IMF. BOB plans to discontinue the use of checks as of 2024. As part of measures to stabilize the pula, BOB has intensified its crackdown on forex bureaus flouting regulations.

CENTRAL BANK OF WEST AFRICAN STATES (BCEAU)

Jean-Claude Kassi Brou | GRADE: Too Early To Say

In June, Jean-Claude Kassi Brou replaced outgoing Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) Governor Tiémoko Meyliet Koné. An Ivorian politician and economist, Brou has a deep understanding of the region. Until his appointment, he was the president of the Economic Community of West African States. Brou is no stranger at BCEAO, having worked at the bank in the 2000s. However, he takes over at a time when the West African Monetary Union, which the bank represents, is grappling with not only economic challenges but also coups and instability. Three of the bank’s eight members–Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger–have been victims of successful or failed coups. Despite the threats, the union is not feeling the intense pain of inflation that is expected to average 6.2% in 2022 from 3.6% in 2021. For this reason, BCEAO has maintained a largely accommodative monetary policy. In June, it decided to raise the key rate by 25 bps to 2.25% to encourage the gradual return of inflation to the target zone.

EGYPT

Hassan Abdalla | GRADE: Too Early To Say

Tareq Amer stepped down as governor on August 17, after seven years at the head of the Egyptian central bank. His successor at the central bank, acting Governor Hassan Abdalla, will face a tough challenge. After a strong performance during the pandemic, Egypt—the world’s largest wheat importer—is now struggling. Soaring food and energy prices have brought inflation to 14.6% in August. As Amer departed, the Egyptian pound was trading at its second-lowest rate on record, public debt hit 90% of GDP, and Egypt entered talks for a new IMF bailout.

ETHIOPIA

Yinager Dessie | GRADE: D

Ethiopia was hoping for a quick end to the war in the country’s northern Tigray region. Combined with external shocks, massive debt, declining foreign direct investment and severe drought, the war is battering the economy and prompting a plea for debt restructuring under the G20 Common Framework. While inflation slowed slightly to 32.5% in August, the birr has fallen by 26% since May. The National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE) has been unable to tame inflation or arrest the black market trading of hard currencies that is shrinking the local currency’s value. The shortage is forcing NBE to continue altering foreign currency retention and distribution rules. Despite the gloom, NBE is implementing a liberalization program of the banking sector by licensing more private commercial banks and allowing foreign banks to invest and set up operations in the country.

THE GAMBIA

Buah Saidy | GRADE: B–

In August, Buah Saidy was elected president of the Association of African Central Banks. For a man who has been at the helm of the Central Bank of The Gambia (CBG) for only two years, this was no mean feat. Seen as progressive, Saidy has the confidence of President Adama Barrow. In May, CBG raised its policy rate by 100 bps to 11% to contain inflation that has spiked to the highest levels in about two decades, to stand at 11.7% in June. The bank hopes to bring it back to its medium-term target in line with a favorable economic outlook. CBG forecasts GDP growth of 4.7% this year. Though the financial sector remains stable and resilient, with non-performing loans (NPLs) on a decline, a decision by Standard Chartered Bank to divest from the country casts a shadow.

GHANA

Ernest Addison | GRADE: B–

Ernest Addison has had commanding control of the Bank of Ghana (BOG) since his appointment in 2017. The past few months, however, have been challenging. In August, BOG held an emergency monetary policy committee meeting that hiked the rate by 300 bps to 22%. Such a substantial hike in one sitting was not expected, and it highlights the BOG’s desperation to stem inflation and stabilize the forex market. This year, BOG has been Africa’s second-most aggressive central bank, having raised its key rate by 750 bps in all, but without notable impact: Inflation accelerated to 33.9% annually in August, an all-time high. The Ghanaian cedi has depreciated by 25.5% against the US dollar since January. The worsening economic situation precipitated street protests, and the government is seeking an IMF bailout.

IRAQ

Mustapha Ghaleb | GRADE: B–

Despite reforms, Iraq remains a hydrocarbon economy. Oil accounts for 99% of the country’s exports and over 90% of public revenues. Given this year’s increase in oil prices, Iraq is on track for recovery. The IMF expects 10% growth, and extra revenues should bring the debt-to-GDP ratio down to 47%, from 66% in 2021. The political context remains extremely volatile, and soaring inflation poses a risk of social unrest. The Central Bank of Iraq (CBI) spent over $10 billion to support companies through private banks but the overall needs are much larger. In a country torn by decades of war and international sanctions, the CBI’s main challenge is tamping down money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (CFT). In 2022, Iraq exited the EU’s list of countries deemed to be high risk for money laundering and CFT, and Governor Mustafa Ghaleb is opening channels with France and the EU to increase correspondent banking relations for Iraqi banks. Climate change is also a rising concern. The CBI is engaging with the issue by offering low-interest loans for water, green and renewable-energy projects.

ISRAEL

Amir Yaron | GRADE: A

Over the last year, Israel’s economy had one of the world’s fastest recoveries in GDP, with one of the lowest levels of inflation. Economists see inflation climbing above the official target of 1%-3% but still lower than elsewhere. According to Reuters, Israel’s “economy grew 8.2% in 2021 and is expected to expand at least 5% in 2022 and 4% next year, while the jobless rate stands at 3.5%.” “With the economy no longer in need of emergency policy support, the central bank acted relatively quickly to phase out its unconventional monetary policy tools,” says Liam Peach, an emerging markets economist at Capital Economics. But it is a delicate balance to suppress growth just enough. “The ongoing tightening cycle by the Bank of Israel [BoI] will drive up lending rates, discouraging credit-based purchases,” says Gabriele de Leva, a Middle East and North Africa country risk analyst for Fitch Solutions. “This will cause output expansion to ease in coming months.”

JORDAN

Adel Al-Sharkas | GRADE: Too Early To Say