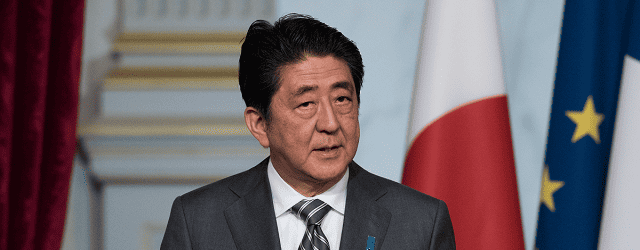

The abrupt announcement that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was resigning for health issues after nearly eight years in power startled the world.

He will be remembered as the first prime minister to be born after World War II and the longest-serving, for his audacious economic policies and for bolstering the country’s defense capabilities, for being very popular and then very unpopular—and yes, for teasing the 2020 (now 2021) Tokyo Olympics by dressing as the video game character Super Mario during the closing ceremony of the Rio Games in 2016. The abrupt announcement that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was resigning for health issues after nearly eight years in power startled the world; Japan without him, many argued, is now difficult to imagine.

The grandson of a prime minister and son of a former foreign minister, Abe was elected to parliament in 1993 and quickly moved up the ladder of the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party. He became prime minister for the first time in 2006, a stint plagued by scandals in his cabinet and an electoral defeat. By 2012, however, Abe had managed to stage the most unlikely of comebacks, returning to the top political post and promising to revitalize the nation’s economy and revive its global standing.

At first, he succeeded. His approach, which came to be known as “Abenomics,” combined fiscal stimulus, monetary easing and structural reforms to pull the Japanese economy out of two decades of secular stagnation. Those early successes, however, had subsided in recent years, then were obliterated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the economy was strong, his conservative policies did not pose a problem, but when growth slowed, cracks emerged in Abe’s support base. His approval ratings during his last days in office were in the low 30%-40% range.

“Abe was the leader of the conservatives, and as such it was only natural that he would represent their views in politics,” says Hideya Kawanishi, professor of history at Nagoya University. “He paid very little attention to those who had different ideas.”

The prime minister’s closeness to US President Donald Trump also hurt him. “Strategically speaking, emphasizing the Japan-US alliance made sense,” says Kawanishi. “The majority of the public, however, did not view their friendship favorably.”

Abe, in Kawanishi’s opinion, widened divisions in Japanese society: “His successor will be judged in no small part on their ability to heal those divides.”